PART II (Read Part I here.)

Prominent Arizona Oath Keeper Jim Arroyo turned on his hands-free microphone and stepped in front of the bright yellow banner of the Yavapai County Preparedness Team to explain “Operation: Drop Box.”

“We’ve already coordinated with Sheriff (David) Rhodes,” Arroyo said during a July meeting of the Yavapai County Preparedness Team (YCPT), an Oath Keepers group that broke ties with the national organization after the Jan. 6, 2021 attack on the U.S. Capitol. “He told us if we see somebody stuffing a ballot box and we get a license plate, they will make an arrest and there will be a prosecution.”

The Election Day operation, which aims to station monitors at every ballot-drop location in Yavapai County, is being spearheaded by YCPT’s sister organization, the Lions of Liberty. On its website, the group instructs monitors to show up with phones or cameras to photograph anyone “putting more ballots in than their own,” as well as the person’s car and license plate.

“Do NOT engage,” the group advises. “Contact us and we’ll get in touch with Sheriff Rhodes who is already aware of what we are doing and will do what he can.”

Like Rhodes, who declined to be interviewed for this story, sheriffs of all political stripes have found themselves thrust into the election integrity arena in response to threats against election workers and an onslaught of debunked allegations of voter fraud. Yet a select group of sheriffs across Arizona and the nation have welcomed the shift, embracing the radical ideologies of the “constitutional sheriff” movement.

Election and domestic extremism experts have sounded the alarm about this “small but vocal subset of sheriffs” who they say are seeking to expand their role into election administration, without any lawful basis to do so. They warn that constitutional sheriff groups are compounding problems created by disinformation campaigns and undermining public confidence in elections and law enforcement, setting the stage for situations that can lead to voter intimidation and ultimately subvert free and fair elections.

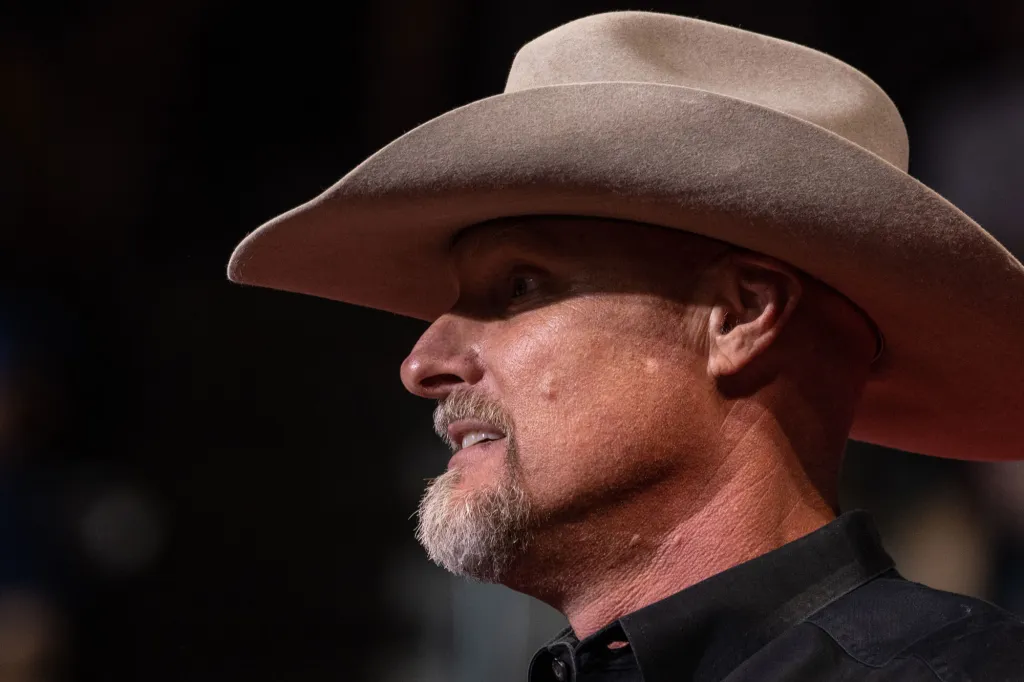

Among those on the front lines of the movement are former Graham County Sheriff Richard Mack and current Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb. Mack, a former board member of the Oath Keepers militia, founded the Constitutional Sheriff and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA) in 2011, while Lamb helped create Protect America Now, built on the same principles, in 2020.

CSPOA Founder Richard Mack waits to speak at an Arizona Oath Keeper meeting in Yavapai County, Ariz. on Oct. 8, 2022. Photo by Isaac Stone Simonelli | AZCIR

Protect America Now frontman and Pinal County Sheriff Mark Lamb speaks at a rally in Prescott, Ariz. on July 22, 2022. Photo by Isaac Stone Simonelli | AZCIR

The groups—both of which have been labeled anti-government extremist organizations by the Southern Poverty Law Center—are leaders in the constitutional sheriff movement, which was built around a radical ideology that the sheriff’s power within his or her county is superseded by no state or federal government entity and is guided by the sheriff’s interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.

The stance, which advocates for sheriffs to nullify any law they deem unconstitutional, presents a new suite of threats to the mechanisms of democracy.

“It really seems like we’ve got a movement of rogue sheriffs aligning with the movement that is continuing to double down on the false, fraudulent election theory and continuing to spread disinformation about it,” said Mary McCord, executive director of the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection, who provided an expert statement for the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the U.S. Capitol that included a warning about the constitutional sheriff movement.

“That’s a pretty dangerous maxim,” she said.

An investigation by the Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting identified more than half of the state’s 15 sheriffs as supporting aspects of the movement’s core ideology, with nearly a third having direct connections to one or both groups. Though AZCIR found no evidence of Arizona sheriffs directly interfering in elections, as sheriffs like Michigan’s Dar leaf and Florida’s Wayne Ivey have been accused of, experts contend the movement overall has merged with larger anti-democratic efforts that have swept the nation.

“The ultimate goal of the anti-democratic forces in this country is to weaken participation, to weaken investment in democracy, to delegitimize the process,” said David Becker, executive director and founder of the Center for Election Innovation & Research, a nonpartisan nonprofit focused on election security and accessibility. He described efforts to draw current law enforcement into the election denial movement and to “use the tools of law enforcement to bully and intimidate voters, public servants, election officials and others, to subvert American democracy” as a legitimate concern.

Expanded sheriffs’ roles fueled by ‘conspiracies, conjecture’

Election officials and law enforcement professionals generally agree that law enforcement can play a critical role in the election process, from protecting election workers to ensuring the secure transport of ballot boxes.

“Arizona was kind of like ground zero last election,” said Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone, who is not aligned with the constitutional sheriff movement. “This agency was cast into the space where suddenly we were more involved in protecting physical structures and people because of this outpouring of concern over the election than I ever expected.”

When it comes to investigating election laws, however, only the state attorney general, county attorneys and municipal attorneys have the power to enforce suspected violations. Assistant Secretary of State Allie Bones said sheriffs would be expected to work closely with officials who launch election-related investigations.

Lamb and Santa Cruz County Sheriff David Hathaway nonetheless have said they don’t believe investigations into alleged election fraud need to start with a request from election officials, a stance being promoted nationally by Protect America Now and CSPOA.

“We’re seeing a push for individuals to step outside their traditional lane—their constitutional, elected officer’s lane in many cases—and pick up the mantle that’s based on conspiracy, conjecture and mis- and disinformation,” said Tammy Patrick, a senior elections adviser for the Democracy Fund who previously spent 11 years as a federal compliance officer in Maricopa County’s Elections Department.

In Michigan, CSPOA speaker and Barry County Sheriff Dar Leaf was named in a probe alleging backers of former President Donald Trump illegally accessed voting equipment seeking evidence of fraud. Leaf has denied any wrongdoing.

Lamb, for his part, has coordinated with local election officials to develop at least one voter education campaign about this year’s ballots. But he has also publicly appeared alongside prominent election-deniers, such as those among a slate of candidates at a Trump-led rally for gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake in Prescott in July.

“We’re going to make sure that we have election integrity this year,” Lamb told an enthusiastic, partially full stadium gathered to support candidates such as attorney general hopeful Abraham Hamadeh and Mark Finchem for secretary of state. Finchem, an Oath Keeper who was present during the Jan. 6 attack at the U.S. Capitol and has repeatedly said he would not have certified Arizona’s 2020 election results, stands to take control of the state’s election system next year if he wins in November.

“Sheriffs are going to enforce the law,” Lamb told the crowd. “This is about the rule of law… We will not let happen (in 2022) what happened in 2020.”

Lamb also talked up a partnership with True the Vote, a controversial election-monitoring group based in Texas. Both CSPOA and Protect America Now have aligned themselves with the organization, which played a leading role in “2,000 Mules,” a largely discredited film that claimed to present proof of widespread voter fraud in the 2020 election.

Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich asked the federal government to investigate True the Vote this month because it has failed to provide evidence to support the allegations that it, CSPOA and Protect America Now are using, in part, to justify sheriffs’ expanded roles in elections.

The groups’ proposed collaboration with True the Vote includes two components aimed at cementing an expanded role for sheriffs in elections: a hotline connecting residents to sheriffs’ offices “for quick evaluation of incoming information” about election concerns, and a series of trainings, resources and tools to help sheriffs “have real-time eyes” on voting in their counties. Mack described the project as resource-sharing, painting CSPOA as a middleman connecting sheriffs concerned about election fraud with True the Vote’s election “specialists.”

Both elements of the collaboration were slated to already be up and running, but there have been no updates to the collaboration’s website to indicate they have started. AZCIR was unable to confirm how much money has been raised through the project, which is underwritten by True the Vote, or how that money has been used.

Lamb suggested AZCIR contact Nathan Sproul, the longtime Republican strategist who incorporated Protect America Now, for details about what the collaboration had accomplished so far. Sproul, who has a history of becoming entangled in election scandals, did not respond to multiple requests for an interview. Neither did True the Vote.

Misinformation undermines election security, integrity

Fallout from the 2020 election has resulted in an uptick in threats against election officials, with one in six saying they’ve experienced intimidation in connection with their work, according to a survey by the Brennan Center for Justice, a left-leaning, Washington D.C.-based think tank. The same survey found 20 percent of local election officials planned to leave their positions before the 2024 election.

Many are already gone, and experts say disinformation pushed by constitutional sheriffs and others is at least partly to blame.

“We’ve seen the impact of misinformation around elections, false information, false claims, how damaging it has been to public faith in democracy, but also to the willingness of election workers election officials to continue to stay in the job,” said Lawrence Norden, senior director of the Elections and Government Program at the Brennan Center. “All of this is more dangerous if it’s law enforcement that is spreading misinformation.”

Experts also worry that some sheriffs’ rhetoric around election fraud, combined with openly sympathizing with residents intent on “verifying” election integrity on their own, could lead to individuals intimidating voters.

The nonpartisan Protect Democracy Project recently called the Lions of Liberty’s planned dropbox monitoring efforts “textbooks examples of voter intimidation.” The Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit sent a demand letter to the group telling it to “cease any plans” to monitor drop boxes and to preserve records because “litigation is imminent.”

While the Lions of Liberty intend to proceed with monitoring “to help secure our election,” according to a statement, board member Lucas Cilano previously told AZCIR the group would not be “engaging anyone” at drop-off sites.

“We are simply watching the drop boxes, and we are hoping that our presence is enough to deter a (ballot) mule,” Cilano said.

Becker, who served as a senior trial attorney in the voting section of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, worries that advertising and amplifying the messages of dropbox monitoring alone could have a chilling effect on voters.

“It’s important to note that if, for whatever reason, whether it’s legit or not, that you think there might be some concern about a particular method of voting, Arizona gives you a lot of options to vote,” he said. Arizona also allows caregivers, family members, household members and election officials to help return voters’ completed ballots, including by dropping them off, according to the Secretary of State’s Office.

Cilano said all relevant information gathered during the group’s planned ballot box monitoring initiative would be handed over to the Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office, not election officers. He said he personally discussed the group’s efforts with Sheriff Rhodes, who AZCIR has identified as aligned with the constitutional sheriff movement.

Rhodes fielded questions about what he’s doing to secure elections at a September meeting of the YCPT, mostly deferring to the county Recorder’s Office. At the time, he did not push back on the Lions of Liberty’s approach to monitoring elections, despite the group calling for volunteers earlier in the meeting.

Yavapai County Sheriff David Rhodes speaks to a packed house at a local Oath Keepers’ event at the First Southern Baptist Church in Chino Valley, Ariz. on Sept. 9, 2022. Photo by Isaac Stone Simonelli | AZCIR

But, on Wednesday, his office published a Facebook post stating that “placement of multiple ballots at a time by one person does not in and of itself constitute a crime, nor is it suspicion of a crime.”

“It is difficult to know each voter’s circumstance so your behavior towards others attempting to cast ballots must not interfere with that person’s right to vote. Should your actions construe harassment or intimidation you may be breaking Arizona’s voter intimidation laws,” the post states.

According to his office, Rhodes was contacted by the Lions of Liberty about the legalities of the surveillance but “wasn’t informed at the time” that there would be filming or photography.

“He is not supporting the box-watching,” his office wrote in response to reporter inquiries.

Earlier this month, a fact sheet attempting to correct misinformation about sheriffs’ role in elections was released by the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection and States United Democracy Center, a nonpartisan, Washington, D.C.-based organization focused on elections.

“Left unaddressed, sheriffs who overstep their roles may not only violate the law, but also may give the impression of attempting to interfere in an election or preventing duly authorized election officials from fulfilling their responsibilities,” the fact sheet warns. It is one of several ongoing efforts, including those by the Committee For Safe and Secure Elections, intended to combat the escalating tensions around the election by helping law enforcement, election officials and the public understand their roles in safe and secure elections.

“Sheriffs have a supportive role when it comes to providing election security, as does any local law enforcement agency,” Assistant Arizona Secretary of State Bones told AZCIR. “They’re not there to dictate how things are going to run or anything like that—that’s left to the election experts.”

Bones said election officials need sheriffs to be partners in ensuring election integrity, “not adversaries.”

Republished with permission from Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting, by

Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting

The Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting is the state’s only independent, nonpartisan and collaborative nonprofit newsroom dedicated to statewide, data-driven investigative reporting. AZCIR holds powerful people and institutions accountable by exposing injustice and systemic inequities through investigative journalism.