Despite years of dizzying election controversy, election administrators see their profession and its rules more clearly than ever. False claims that their work in the last general election was fraudulent have mainly served as motivation to strengthen the procedures and systems that ensured 2020 results withstood expert and legal scrutiny.

That doesn’t mean the waters have calmed. “Our overriding concern is about voter confidence,” said Ricky Hatch, the clerk/auditor for Weber County, Utah. Hatch also serves as chairman of the National Association of Counties elections subcommittee.

“Safeguards have been in place for years and we tweak and improve every year,” he says. “We feel confident about them, but we want voters to feel confident.”

Agitators have created enough noise that it’s hard to gauge exactly how voters feel. According to an October survey by Morning Consult, 54 percent of Americans have “some” or “a lot” of trust in the electoral process, the highest percentage since March 2021. Trust levels vary significantly between Democrats (67 percent) and Republicans (44 percent).

Recent state-level polls show even greater levels of confidence. A poll of Utah voters found that 89 percent believe the upcoming election will be fair and accurate. Even though Arizona has been a high-profile playing ground for conspiracy theorists, 77 percent of the state’s voters believe the results of the November general election will be accurate.

Brianna Lennon, the clerk for Boone County, Mo., is looking past Nov. 8. “The bigger concern that I have is that this is more of a test run for 2024,” she says. “I’m thinking this is not as bad as it’s going to get, it’s just a smaller election.”

Workers in the Detroit Department of Elections insert test ballots into machines during a public accuracy test. (Clarence Tabb Jr./TNS)

A Minefield of Potential Trouble

The prospects for trouble vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, says Lennon, who hosts a national podcast about election administration. While she’s heard reports of threats and physical intimidation in other states, this isn’t happening in Missouri.

Weber was surprised to see more than 20 protesters show up at the logic and accuracy testing of voting equipment in a nearby county with a relatively small population, something Weber County didn’t experience. The county officials got through the testing, he says, but it was difficult.

“I expect more things like that to happen. There are active groups that are going to come out and make things uncomfortable, but hopefully not unsafe.”

The presence of “observers” trained by election deniers could bring more of the misguided “exposés” seen in 2020, Hatch says. Onlookers who were unfamiliar with the details of election administration perceived routine procedures (or even the sharing of mints) as evidence of fraud, and saw their claims echoed by high ranking government officials.

“It’s like the five blind guys and the elephant,” says Hatch. “If you’re touching the elephant’s tail and that’s all you know, it’s not the same as seeing the whole elephant — or understanding the whole elections process.”

Mis- and disinformation remain major challenges for local election officials, says Tina Barton, a long-time city clerk for Rochester Hills, Mich., who is now assisting colleagues throughout the country as senior election expert for The Elections Group, an advisory organization for state and local election officials. “I have consistently heard from local election officials that they need help with communication tools and amplifying their messages,” she says.

“A dehumanization of election workers and election administrators is taking place,” says Barton. “They are receiving horrible threats, profanity-laced name-calling, and sexually intimidating messages.”

The fact that these pressures are causing trained and experienced professionals to leave their jobs is the “Real Great Resignation,” she says, due to its potential to weaken American democracy.

Protestors in front of the Shasta County clerk’s office during a February 2022 recall election. Deniers may not represent majority opinion, but their voices are loud. Anita Chabria/TNS

The Long Shadows of Deniers

Neal Kelley, recently retired after a long career as registrar of voters in Orange County, Calif., is the chair of the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections (CSSE). The group, comprised of experts from election administration, law enforcement and cybersecurity, was formed to support local officials. Hatch and Barton are both members.

Kelley’s biggest concern is that groups continuing to push fraud claims could trigger violent behavior by an unstable individual. “That’s the consequence that a lot of these folks who are election deniers are not thinking about, or in some cases not caring about,” he says.

Michigan officials have expressed concerns about election violence, but Hatch doesn’t expect such events to be widespread. That doesn’t mean jurisdictions can ignore the possibility. “All it takes is one person,” he says. “Unfortunately, that’s the one we have to plan for.”

One of the priorities for CSSE is to connect election officials with local law enforcement, to bolster communications and to help law enforcement officers become aware of sections of election code which define criminal conduct in the context of elections.

In support of this mission, CSSE recently sent a training video to thousands of law enforcement agencies with guidelines for preventing violence at polling places.

A video produced by the Committee for Safe and Secure Elections outlines steps that can prevent violent disruptions at polling places.The video, along with other resources CSSE has developed, include state-specific references for law enforcement. It has helped facilitate discussions between election offices and police. A multi-county meeting was just held in Utah, and Hatch is aware of similar events in Colorado, North Carolina and Iowa. “The biggest thing is that it got us in the same room.”

Election officials also have been flooded with public information requests, often cut and pasted without personalization. Software is being developed to help sort through repetitive requests, Kelley says. In the meantime, officials are obliged to respond to them, creating overwhelming workloads.

Some counties have put documents related to redundant inquires online and are referring those who file requests to their websites, says Lennon. Based on her experience, it’s likely this will be the end of any dialogue.

“I have answered requests for clarification with extremely detailed responses, along with invitations to come to our office and visually walk through what they’re talking about,” says Lennon. “We never get responses back.”

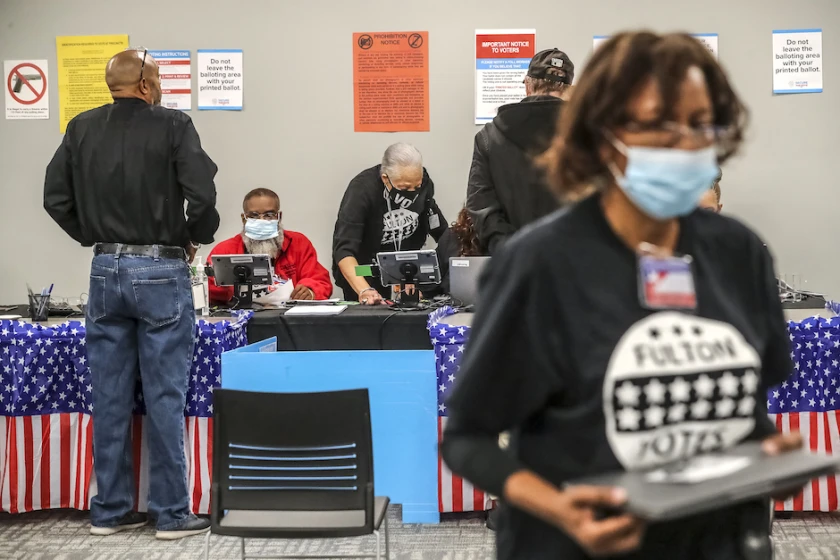

The first day of early voting in Georgia as seen on Oct. 17 at the Buckhead Library in Atlanta. As of Oct. 18, turnout was 85 percent greater than during the same period in the 2018 midterm elections. (John Spink/TNS)

Public Statements of Support Would Be Helpful

The confidence level of election officials is higher than ever, according to Hatch. Even so, they are going above and beyond regular controls and creating the most transparent process possible in anticipation of possible fraud allegations.

“When the public sees those allegations, we want the public to have resources from reliable sources that can help them feel confident the allegations aren’t based in fact,” he says.

CSSE has developed a range of tools for both election administrators and law enforcement, from a series of “steps for safer elections” to a curated group of government agency and NGO resources.

Materials available from The Elections Group include guides for de-escalating tense situations, ballot replication, logic and accuracy testing of voting systems and box office security. “Standards of Conduct for Election Workers” sets expectations for participant and observer behavior in normal elections.

Election officials have long sounded the alarm for more support, and even though elections were designated as critical infrastructure as long ago as 2017, they have not been funded as such. Changes in voter habits, such as absentee voting, may mean more staff, notes Barton. In the current era of election denial, funds are also needed to increase security measures to keep election officials, offices, workers and precincts safe, she says.

Kelley sees awareness of such needs growing at a “slow burn,” a situation that may change depending on what happens in November. “I think we’re going to have to get through these midterms and see what shakes out,” he says.

Former NPR Correspondent Pam Fessler talks about the use of storytelling to bolster public understanding and trust.The biggest boon that government could give to election officials as the midterms approach is one that was largely withheld in 2020: public statements acknowledging the integrity of the American elections process. Privately, Hatch and his colleagues were assured that they had the trust of leadership — but those expressing these sentiments remained silent in public out of fear of a vitriolic response.

“A public expression of confidence really would go a long way.”

At a more fundamental level, Barton hopes voters can recognize that election officials and workers are their neighbors, not the malignant “other” portrayed in social media.

“We attend church with them, our kids go to school together, we shop at the same grocery stores and eat at the same restaurants,” she says. “We are people who love this country.”

Republished with permission from Governing Magazine, by Carl Smith

Governing

Governing: The Future of States and Localities takes on the question of what state and local government looks like in a world of rapidly advancing technology. Governing is a resource for elected and appointed officials and other public leaders who are looking for smart insights and a forum to better understand and manage through this era of change.