My favorite Richard Nixon story is about the day I learned that in his youthful days as a congressman, the man was a horndog. It was August of 1973, I was in Miami on one of my trips to the Pray For Rain state, called that because it was so hot in the summer sun, your feet got stuck in the pavement crossing the street. I was in town for the Village Voice, covering my little corner of the Watergate story—Bebe Rebozo, Nixon’s best friend since he was introduced to him in 1950 by Florida Congressman George Smathers, who recommended Key Biscayne as a winter vacation spot o the young congressman. At Smathers’ urging, Rebozo took Nixon deep sea fishing, and the two men became friends for life.

But what kind of friends, I wanted to know after Rebozo was linked to the infamous Howard Hughes $100,000 donation to Nixon’s reelection campaign in 1972. It was known that Rebozo had helped Nixon buy his “Winter White House” on Key Biscayne years before, and a second house on the same block more recently, so Rebozo and Nixon were involved together in real estate deals, but what else might be going on behind the scenes?

I was living at the time with a woman whose family had some good connections at Harvard, and through her I was put in touch with a member of the Harvard Board of Trustees who was a prominent attorney in Miami and was said to know a few things about Bebe and Nixon. Boy, did he! One of the rumors I was chasing down, along with other reporters long curious about the sex life of the apparently sexless Nixon, was that he was gay. It so happened that the Miami attorney was prominent in Miami’s gay community, so I asked him: What’s the story on the rumor that Tricky Dick is secretly on the bus, as the saying went in the gay community back then.

We were out on his yacht with gin and tonics in hand cruising Biscayne Bay, and if you had been in a car with the windows rolled up in the middle of traffic on South Beach Boulevard miles away across the water, you could have heard the guffaw that came out of him. “My God, if he was, we wouldn’t have had him!” the man said. He then launched into colorful stories of having witnessed Rebozo squiring Nixon around Key Biscayne and Miami Beach in a baby blue Buick convertible back in the early 1950’s, both men accompanied by young women who were not their wives in colorful swimming attire. “Rebozo was Nixon’s pimp,” my Miami source said. “I mean, being married to Pat? Everyone knew he couldn’t keep it in his pants.”

In years of observing Nixon’s political career, and during the months I had spent covering him during Watergate, learning Nixon was a horndog was the only human thing I had ever heard about the man.

I wasn’t aware of this when I was assigned to cover the Republican National Convention in Miami Beach the year before, however. It was another August in Florida, the state where the Heat Never Sleeps. The assignment had come out of the blue from an editor I knew at the late lamented Saturday Review magazine, and the deal was, they wanted copy for the magazine to meet a print deadline on the day after the convention ended on Wednesday, August 23. Apparently, the two guys they had wanted for the piece before they called me had turned it down because of the tight deadline.

I flew down to Miami a couple of days before the convention started and checked into the Americana Hotel, hoping to pick up some local color before the place was overrun with straw-boater-wearing Nixon men with their Aquanet-helmeted wives, and the swarm I dreaded most, the “Nixon Youth” contingent, the little monsters who were my age and somehow had found reason to adore a man as odious and contemptible as Richard Nixon. Somehow, the Saturday Review had come up with press credentials for me, so the first thing I did was check in with Republican National Committee headquarters at the Eden Roc hotel, smack in the middle of the Miami Beach Gold Coast, next door to the fabulous Fountainbleau Hotel. Both hotels were right on the ocean, with rooms that overlooked the Atlantic on one side and a little sliver of Biscayne Bay that ran right alongside Collins Avenue on the other.

As I walked into the Eden Roc to pick up my credentials, who did I run into but my friend Hunter Thompson, who was in town for Rolling Stone as part of his year-long coverage of the ’72 presidential race. We had known each other since I was a lieutenant in the Army stationed at Fort Carson, Colorado, and he was living in Aspen, struggling to make a living on his royalties from “Hell’s Angels,” the book he had written for Simon and Schuster some years before. He was so broke when I met him in the winter of 1969, Thompson would let me stay in a basement room across from his office, which he called “the war room,” in return for my delivery of a bottle of cheap gin I picked up at the post Class Six Store and some low-cost eggs, milk, cereal, meat and vegetables I bought at the commissary when I drove up on the weekends to ski.

Thompson had been in the Air Force and had been discharged for writing a story about his base commander’s wife stealing money from a local charity for the base newspaper. When we met one afternoon at his friend Tom Benson’s gallery in Aspen, Thompson said, “Hey, you’re that crazy bastard from West Point who’s been writing for the Voice, right?” When I confirmed I was indeed him and told him I was stationed at Fort Carson, he said, “Well, you’re not going to last any longer in the Army than I lasted in the Air Force.” He ended up being right about that, so we had our brief military careers in common, truncated by being simultaneously in the service and being writers.

Back in Miami, we picked up our credentials and somebody at the RNC headquarters told us we were just in time to attend a big press conference by “Celebrities For Nixon” that was going on just then in the hotel ballroom. You have to understand that in 1972, reporters for the major newspapers and the AP and UPI and the television networks were all coat-and-tie wearing men, some of whom actually still wore the kinds of fedoras you may have seen in old movies like “The Front Page.” So when Thompson and I walked into the press conference wearing shorts and sneakers and in Thompson’s case, a loud Hawaiian shirt, heads turned. We took seats in the back and watched as Mary Anne Mobley, a former Miss America, Glenn Ford, and John Wayne took the stage to sing the praises of Nixon. When they were through, Clark McGregor, Nixon’s newly appointed campaign chairman, took the stage for questions.

What we now call the Main Stream Media press corps did not exactly distinguish itself. Nixon’s previous campaign chairman, former Attorney General John Mitchell, had resigned his post in July, soon after burglars, one of whom was employed by the Nixon reelection campaign, were arrested for bugging the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office and apartment complex in Washington, D.C. So, there we sat, with this joke of an array of “celebrity” Nixon endorsers standing before us, with the Watergate story, while still in its infancy, already having caused Nixon his long-time friend and campaign chairman to resign, and from the assembled members of the press? As we say today, crickets.

That is until Thompson nudged me and said, “Fuck it. Let’s ask some real questions.” He stood up in his Hawaiian shirt and aviator shades and yelled out, “Hey, Clark! What about Mitchell!” I stood up and yelled, “What about the Howard Hughes hundred grand?” McGregor didn’t have to contend with us for long, because the Big Time reporters in the room seated in front of us turned around and started shouting at us to sit down and shut up, there was a celebrity press conference going on, and they had some questions for John Wayne. Thompson shot back, “Well, I have one, too. Mr. Wayne, when this is over, will you walk down the street to where the Vietnam Veterans against the war are camped out and talk to them?”

“Sure I will, padnuh,” Wayne said in his fake movie-drawl. “Meet me after this is over.”

We caught up with Wayne and Ford in the hallway after the MSM guys had exhausted their questions of Mary Anne Mobley and the others, and Thompson told Wayne that we were there to escort him down the street to the VVAW encampment. “You don’t think I was serious in there, do ya, padnuh?” Wayne fake-drawled, laughing. Turning to his fellow movie star, he said, “C’mon, Glenn, I need a drink.”

Thompson gave me the number for a typewriter rental place I could call to get an IBM electric delivered to my hotel so I could get the Saturday Review piece written before flying back to New York, and we repaired to the Poodle Lounge at the Fountainbleau for a few drinks of our own.

Thompson stayed on the road with both the McGovern and Nixon campaigns into November, producing his classic Rolling Stone coverage that he would turn into “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72,” which in my opinion is one of the best books on American politics ever written. The Watergate story drip-drip-dripped into the fall and winter, with one famous revelation after another coming to light, and when I spied a line in one of stories that leaked out about Nixon trying to get the CIA to warn-off an investigation of the Watergate break in by the FBI because he didn’t want “the whole Bay of Pigs thing” coming to light, I started looking into the links between the Nixon campaign and the Miami Cuban community, which started with some of the burglars like Eugenio Martinez and Virgilio Gonzales and Frank Sturgis and would soon turn up former CIA man Howard Hunt. It didn’t take long for the name of Bebe Rebozo to pop up, and I started to pick up my NY-Miami frequent flyer miles chasing down leads on Bebe.

By the time the Senate Watergate Committee started holding hearings in May of ’73, Rebozo’s name had been linked to funneling secret campaign donations to Nixon, and he was looking more and more, to me anyway, like Nixon’s bagman.

If there was one other thing besides being a horndog that Nixon had in common with crook-of-the-moment Donald Trump, it was a love of money. Here was a man who in his entire adult life had been employed outside of government service for only eight years, between 1961, after he left the Vice Presidency, and 1969, when he returned to the White House as president. He worked during that time for the white-shoe New York lawfirm, Mudge Rose, but there was never even a whisper of talk about any real work he did as a lawyer during those years. My Miami lawyer friend, who as a trustee at Harvard, was extremely well-connected in the world of big-time lawyering, told me that Nixon was famous at Mudge Rose for being willing to attend the opening of an envelope, even if it involved travel overseas, if it meant he was eligible for extra pay as per diem, and especially if while he was on the job, the client was impressed enough with a former Vice President representing him, that he would award Nixon with a gold watch or even a Waterford crystal vase. Nixon would take his client-presents back to the states and get a friend to pawn them, if the item was not worth much, or even put the stuff up for auction if his gifts ended up having real value.

Nixon was paid around $12,000 a year during his brief time in the Senate in the early 1950’s, and as Vice President under Eisenhower earned a salary of $35,000 a year. When Nixon took office as president in 1969, his pay was $200,000 a year. But this is a man who owned vacation homes in Florida and San Clemente, California, and upon leaving office in 1974, was soon able to afford to buy a home in suburban New Jersey for more than $3 million. Where did a government salary-man for much of his life get all that money? Skillful stock picks? If you believe that, I’ve got a vacation home to sell you in the Hamptons for ten grand.

The Watergate scandal, which resulted in the conviction and jailing of so many of Nixon’s henchmen and (former) friends like John Mitchell, also pulled back the curtain if only a teensy bit on what we might call Nixon’s outside income while he served in his country’s government. The Watergate Committee was able to track at least some of it as it passed through a little bank on Key Biscayne called, naturally, the Key Biscayne Bank, which just happened to be owned by Nixon’s long-time bagman and pimp, Bebe Rebozo. Bebe’s bank was located in a strip mall on island off Miami, and consisted of a single counter and a single teller. When I walked in one day in the winter of ’74 and said I wanted to open an account, the teller, a woman with her gray hair in a bun and reading glasses on her nose, calmly looked me over and said, “We’re not that kind of bank, my dear.”

In its closing days, the Senate Watergate Committee became interested in the role Bebe Rebozo had played in Watergate. When Terry Lenzner, one of the Democratic counsels to the Watergate Committee, read a couple of my Rebozo stories in the Voice, he called me up and told me he was stumped by Rebozo. “Who the hell is this guy?” he asked me. “We think he’s laundering money for Nixon, but we can’t nail him down.” Lenzner’s ears perked up when I told him I had discovered that Rebozo owned a chain of about 90 laundromats in Southern Florida. Laudromats, in those days, were all-cash businesses, taking in the bulk of their money in quarters. Bebe was laundering money through his laundromats. One storefront business would take in, say, $200 in cash for a day, around $1500 for the week. It would be no trouble at all for Rebozo to deposit $3,000 for the week in the bank as earnings, thus putting himself, or his partners, on the hook for paying taxes on the extra $1500 in ill-gotten money that he had added to the week’s laundromat take. Multiply that by 90, keep on multiplying at 52 weeks in a year, and you’re talking some real money.

Lenzner sent Scott Armstrong, one of the committee investigators, down to Key Biscayne to look into Rebozo’s Key Biscayne Bank. Armstrong was on his way from the airport to his hotel when he spied Bebe’s bank in the strip mall on Key Biscayne’s main drag and decided to pull over and have a look. Just as he got out of the car, a man carrying a suitcase exited the bank’s front doors and turned around to lock them as Armstrong approached. He had a Senate Committee subpoena, so he served it on the guy on the spot, and somehow talked him into opening the suitcase, as if the subpoena was a search warrant. When Armstrong looked inside, he saw $750,000 in cash. The man had a ticket for the Bahamas in his pocket. It turned out that he ran a souvenir concession at the Paradise Island Casino. He was apparently heading for the casino to run the chunk of cash through the casino, another infamous form of money laundering.

Did some of that money belong to Richard Nixon? We’ll never know, because once the White House tapes were discovered, and the Senate Committee and the office of the Watergate Special Prosecutor(s) focused their attention on listening to Nixon’s voice as he committed his various crimes, the Key Biscayne Bank and the South Florida Laundromat King, Bebe Rebozo, fell by the proverbial roadside.

It was yet another blistering August, in Washington D.C. this time, when Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency and his rather freshly-appointed Vice President, Gerald Ford, took his place, and the rest is history, as they say. Disappointment, at least among Democrats, reigned when exactly a month later, Ford granted Nixon “a full, free and absolute pardon” for any and all of his crimes while president, foreclosing the kind of moment this nation experienced today when Donald Trump pled “not guilty” in a Miami federal courtroom to the 38 felonies he is charged with in connection with his theft and mishandling of at least 31 highly sensitive top secret documents and his multiple attempts to obstruct the investigation that followed.

Richard Nixon and Donald Trump had another thing in common, which we might sum up by turning to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, where we find the words “sociopath” and “narcissist,” both of which each man appears to have suffered from during their long and rather bothersome lives. The two men differed in one important respect, however. Nixon was obsessed with secrecy and committed all his crimes behind closed doors in the company of and in conjunction with only a few trusted aides. Trump, on the other hand, did what he got indicted for right out in the open, the latest evidence of which we were treated to in the indictment’s accompanying photograph of boxes of government documents, some of which may have included sensitive national security secrets, stored, if indeed that word even applies, on the stage of his public ballroom at his resort and club in Palm Beach, in full view of and completely accessible by club members, Trump friends, Mar-a-Lago employees, and attendees at whatever weddings and bar mitzvas were held there during the time last year the boxes of documents resided on the ballroom stage.

What can we call these two men who occupied the highest office in the land without embarrassing ourselves as citizens too much? Our national id? The hidden part of our collective personality as a people that accounts for the atavistic needs of our democracy’s dark side? I looked up “id” on the internet, just to get a flavor for how psychologists see it, and found this on a site called, appropriately enough, Verywellmind.com: “An example of the id is a toddler that wanted a second helping of a dessert and whined until it was given to them.”

Which, complete with its mistakes in usage and pronouns, pretty much sums up both Nixon’s and Trump’s presidencies. Nixon adorned his White House guards in white and gold uniforms complete with silly epaulets and funny hats when he wanted to impress foreign dignitaries for whom he was putting on state dinners in the White House. Trump famously wanted all of his military toys to be paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue for the 4th of July or some other occasion after he had visited France and seen a similar military display on the Champs Élysées put on by the much younger, thinner, and better-married Emmanuel Macron for Bastille Day in 2017.

We should be ashamed of ourselves for electing these two as president, one of them twice, but for that kind of collective shame to happen, it would necessitate a great majority of us not being found somewhere in the charts and graphs of the psychiatric DSM-5. For now, at least, that’s simply not the case. We elected these two certifiable loons and put the so-called nuclear football within grabbing distance of them both. We’re as crazy as they are.

Republished with permission from Lucian K, Truscott IV.

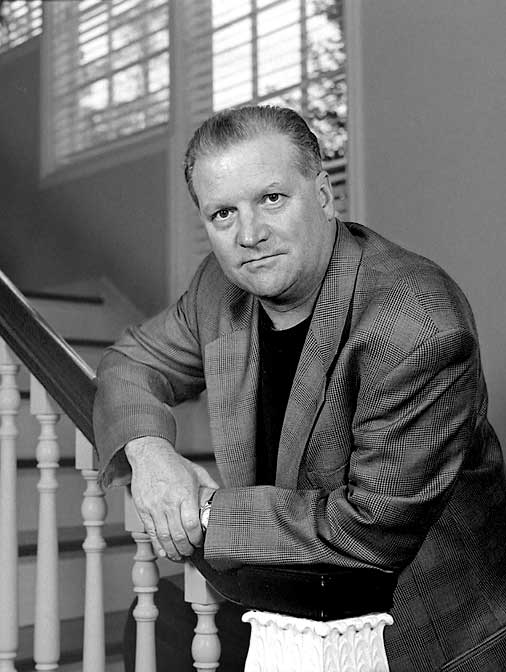

Lucian K. Truscott IV

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He has covered stories such as Watergate, the Stonewall riots and wars in Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels and several unsuccessful motion pictures. He has three children, lives in rural Pennsylvania and spends his time Worrying About the State of Our Nation and madly scribbling in a so-far fruitless attempt to Make Things Better.