Republished with permission from Lucian K. Truscott IV

There has been a controversy where I live in the Borough of Milford, Pennsylvania, over whether to pass a resolution in support of Pride Month. This is conservative area, with groups like The Rod of Iron, a cult that worships the AR-15 led by a son of Rev. Moon, based nearby, and there is opposition in the area to endorsing Pride Month. This column is from remarks I made tonight to the borough commissioners in support of Pride Month. The resolution passed in a unanimous vote.

It’s hard for me to wrap my head around the fact that it was 55 years ago next month that I was on my way from my loft on Broome Street to the Lion’s Head bar on Christopher Street in Manhattan when I walked right into what would become known as the Stonewall Riot. That night is what gay pride and Pride Month is about. On June 27, 1969, police from the NYPD vice squad were busting the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar on Christopher Street. A crowd gathered across the street from the bar as cops led gay customers from the bar in handcuffs and put them into the back of what they used to call a “paddy wagon” that had been parked in front of the bar.

When a trans woman protested the way cops were prodding her with their nightsticks, two cops grabbed her and forcibly threw her into the back of the paddy wagon. The crowd began throwing coins at the cops, jeering and calling them “pigs.” Then a paving stone flew through the air and broke the Stonewall’s front window. Two cops slammed shut the back doors of the paddy wagon, and as it drove away, more paving stones were thrown. The cops retreated inside the bar and the crowd surged across Christopher Street yelling, “Let them go! Let them go!”

It was the gay community’s Rosa Parks moment, when a black woman in Montgomery, Alabama, refused to sit in the back of the bus and was arrested, setting off the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which began in December of 1955 and lasted until a Supreme Court decision a year later declared that segregating a mode of public transportation was unconstitutional. It was the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, which led eventually to the Civil Rights and Voting Rights laws of the mid 1960’s.

On the night of June 27, 1969, gay people in Greenwich Village rose up and said, we’re not going to take it anymore. What was it? It was everything—being forced by societal norms to live in the closet if you wanted a job, or to rent an apartment, or to get a loan at a bank, or any of the other ordinary things straight people took for granted. It was illegal in June of 1969 to serve an openly gay person a drink in New York State, so all the gay bars in New York City, including the Stonewall, were run by the mob. The police were paid off to keep them open.

Busts of gay bars like the bust at the Stonewall happened all the time. It was part of the price you paid if you were gay, to get arrested for buying a drink in an establishment open to the public. That night, gay people said, we won’t put up with it anymore. That weekend, as people walked home after squads of cops in riot gear had cleared the streets, was the first time I had ever seen gay people openly holding hands in the street. The chains were off.

I wrote a story on the front page of the Village Voice, “Gay Power Comes to Sheridan Square,” about the Stonewall riot. If you had told me, or anyone for that matter, that a movement would be born that would lead to the decriminalization of gay sex, to same sex marriage, and to gay people, for the first time in the nation’s history, being allowed to serve openly in the military, you would have been asked what you were smoking.

A year later on the anniversary of Stonewall, the first Gay Pride parade marched up Fifth Avenue from Washington Square Park. There wasn’t yet a Pride Month—that would come later—but a movement was born that over a period of the next four decades brought about all those things. Gay people had to fight for rights everyone else already enjoyed.

My part in the gay rights movement was to write about and champion the right of gay people to serve openly in the United States Military. I come from a family with history of military service. My grandfathers and my father and my uncle and my brother and I all served. All we had to do was sign on the dotted line and take the oath and we were soldiers. But during the time we were in the Army, gay Americans had to do something extra. They had to hide who they were, because it was illegal to be gay and serve in the military.

Think about that for a moment. You are a young man or a young woman, and you are patriotic, and you want to serve your country, but if you are gay or lesbian or trans or anything in any way other than heterosexual, you must commit a crime to do your patriotic duty, as perhaps your father or mother or grandfather had done.

Memorial Day will be here next week, when as a nation we mourn those who gave their lives in serving their country in the military. Have you ever thought of how many veterans were gay, or lesbian or trans, whom we mourn and thank on Memorial Day? Have you ever thought of the debt we owe them? Have you ever thought of the patriotism they felt as they wore the uniform, the pride they took in their service to this country?

Let me share a story my father told me many years ago, before the law imposing “don’t ask, don’t tell” was repealed. In the winter of 1950, my father was serving in the 2nd Infantry Division as a company commander. His unit was part of an attack ordered by General Douglas MacArthur to drive the Chinese Army out of North Korea. To put it bluntly, it didn’t work. After a series of battles with the Chinese Army, the 2nd Infantry Division was in retreat through a valley that became known as “The Gauntlet.” His company was bringing up the rear of the retreat under punishing fire from the Chinese Army.

In a last, desperate attempt to escape the valley, my father ordered his men over a hill. Dad’s company was pursued closely by the Chinese army as they took multiple casualties and carried their wounded. As they reached the top of the hill, a machine gunner set up his machine gun and began strafing the Chinese Army as they climbed the hill in pursuit of dad’s company. He stayed there, firing his machine gun, until the last soldiers in dad’s company had carried their wounded to safety. He killed dozens of Chinese soldiers and he was killed protecting the retreat of dad’s infantry company.

After that build up, it won’t surprise you to learn the machine gunner was gay. Since before the 2nd Infantry Division had been sent to Korea to fight, he had been relentlessly harassed and teased and bullied by his platoon mates. Everyone in the company knew this was happening and did nothing to defend him. And yet he stayed on that hill and fired his machine gun defending his company until a Chinese bullet took his life.

Dad told me that the next day after his company had reached safety in the rear area, they held a service for their company mates who had lost their lives. Dad said that when the name of the machine gunner was read out, people started to weep openly. Dad said that despite the fact that others had died that day, and others would be killed as the war dragged on, it was the saddest moment in the war for him, because he had known about the abuse of the gay soldier in his company, and he had done nothing about it, and yet the man gave his life to save his fellow soldiers.

I tell you this story because I want you to think about where patriotism and pride come from, and what they really are. Patriotism isn’t a right; it is a privilege that is born in the heart. Pride isn’t just about a lifestyle or sexual identity. Pride is about what we all gain when we are free and can celebrate that freedom together, as individuals and as citizens of our great country.

Pride is a dish best served warm, and from the heart. I hope you will join us as we celebrate Pride Month together.

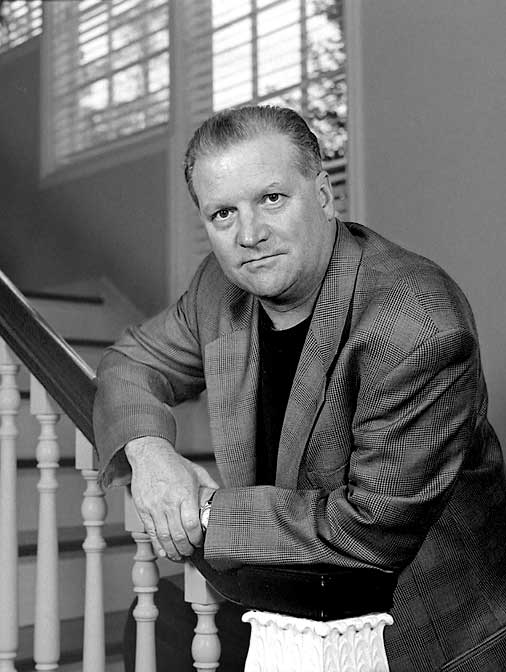

Lucian K. Truscott IV

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He has covered stories such as Watergate, the Stonewall riots and wars in Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels and several unsuccessful motion pictures. He has three children, lives in rural Pennsylvania and spends his time Worrying About the State of Our Nation and madly scribbling in a so-far fruitless attempt to Make Things Better.