Republished with permission from Lucian K. Truscott IV

Whether you believe in God or not, I am here to tell you that we should consider ourselves blessed that the national political conventions of our two parties are held only once every four years. The word bacchanalia is appropriate to describe every single one of them.

When I was flying from New York to Miami to cover the 1972 Republican National Convention that would crown the well-known conservative, Richard Nixon, I sat next to an attractive, very well-dressed young woman wearing heels and carrying a beautiful red oversized leather purse. We got to talking, as you do on airline flights. I told her that I was covering the convention for the Saturday Review magazine. When I introduced myself, she recognized my name from reading the Village Voice.

I asked her what she was doing on a flight to Miami just before the Republican Convention. “Working,” she said. She turned around in her seat and signaled to two friends, similarly attractive and attired, sitting behind us to come forward to where we were sitting. The three of them were prostitutes, call girls in the slang of the time, who lived on the Upper East Side and worked through an out-call operation that advertised in the Voice classifieds.

Political conventions were a prostitution gold mine, it turned out, especially the Republican convention. “It’s like they get permission to go crazy for a week,” the young woman sitting next to me said. She glanced around the cabin to see if anyone was looking and pulled up her just-above-the-knee skirt to show me a thin leather wallet tucked into a garter on her thigh. “I’ll have to empty this thing out a couple of times a day, it will get so full of twenties and hundreds,” she said. All three of them giggled. “The ones from the deep South are the best,” one of them said. “They’re so glad to get away from their little towns and their little churches and their little wives, they just throw money at you.”

When we landed in Miami, I learned why the three women were so conservatively dressed. Miami cops had several young women wearing mini-skirts and very high heels and a lot of make up in a roped-off area in arrivals. One of the women from our flight pointed them out and explained that they would be quickly be put back on a flight to wherever they came from. “Cops can do that?” I asked, incredulous. “Honey, cops can do anything they want to working girls,” came the answer. We exchanged the names of the hotels we would be staying in so I could interview them about their experiences later in the week. All three had reserved rooms over a year previously at the Fontainebleau when they heard on the working-girl grapevine that the Republican Convention would be held in Miami Beach. I was a couple of miles up the beach in Bal Harbour (with a “u” my dears) at the slightly less grand Americana.

That was on a Saturday in early August. On Wednesday, I met the three of them at Wolfie’s Deli for breakfast. They were bright-eyed and fully made-up, wearing casual sundresses and big straw hats, their daytime mufti during the convention. One of them had averaged $1500 a night, the others almost as much. This was 1972, mind you. They had latched onto one of the delegates from Los Angeles and all three of them were taken to the Eden Roc, the hotel headquarters for the Republican Party, and had met Sammy Davis Jr., who would become famous the next night for seeming to climb the leg of Richard Nixon in an appearance at a “youth rally for Nixon” later that day. It would later emerge that Nixon used racist epithets for Black people in the Oval Office in speaking with aides. His disassembly of the “Great Society” inner city programs of Lyndon Johnson was a hallmark of his first administration. Davis’ awkward embrace quickly became a famous image and haunted the career of the singer, who made no secret of the fact that he was a loyal Democrat. He would later tell a friend that he appeared at the “youth rally” because Nixon had made an enormous tax bill “go away.”

Nixon’s appearance at the “youth rally” in Miami Beach that year was part of a larger campaign to soften his image as a candidate. Sammy Davis Jr., believe it or not, was an attempt by the unusually grim and buttoned-up Nixon to appear “hip.”

Kid Rock stood in for Trump’s attempt at a woeful stab at hipness last night in Milwaukee, bringing his Midwest bona fides to the stage wearing a gigantic bejeweled cross on a chain around his neck under a black leather biker jacket and leading the crowd in a fist-raising chant of “fight, fight” with screens showing gigantic flames behind him as he broke into a rap that was built, as closely as I could determine, around the “fight, fight” as he shouted “throw a fist in the air and lemme see where you at” and “they want to see us fry, I guess because only God knows why, why, why.”

The network cameras panned the crowd, heads nodding, confused looks on their faces as Kid Rock broke into this necklace of lyrical gems:

With tracks that mack and slap back the wack

Never gay, no way, I don’t play with ass

But watch me rock with Liberace flash

Punk rock, the clash, boy bands are trash

I like Johnny Cash and Grandmaster flash, flash, flash, flash, flash

The crowd in the hall was decked out in red, white, and blue in everything from typical “funny” hats to tiger stripes to hair-glitter, thrusting signs that read “Mass Deportation Now!” in front of the box where Vice presidential nominee J.D. Vance and his wife, the daughter of Indian immigrants, stood with blank looks on their faces, nodding along to Kid Rock’ rap with Eric and Donald Jr., sons of Trump’s immigrant first wife.

Here’s the thing about political conventions: Apart from their actual purpose, to nominate a presidential candidate, they are ridiculous exercises in excess and what we now call identity signaling. The crowd in Milwaukee, as was the crowd in Miami in 1972, relentlessly white. The crowd at the upcoming Democratic Convention in Chicago will be wildly mixed, ethnically and racially. This is always the way of our two major political parties, one party making no bones about representing those who own businesses and land and things, the other party representing those who, symbolically anyway, rent from the owners.

Donald Trump’s appearance on stage after Kid Rock and Hulk Hogan—professional wrestling having become yet another political signifier—was, if anything, anticlimactic. Many commentators described Trump as “subdued.” He was, especially in the first thirty minutes when, as advertised, he made an attempt at “moderation” and “unity,” two words heretofore not in the Republican Party dictionary. But even when he hit the red meat of the last hour of the speech—it was the longest acceptance speech in American political history, naturally—he appeared to robotically read the words from the teleprompter, only occasionally inserting impromptu asides where his usual rabid calls to racism and the other isms reside.

After the convention was over, my newsfeed lit up with commentators and Substackers and just plain folks crying out various takes on “we can beat them!” You would have said the same thing after Richard Nixon’s 1972 coronation—a deeply unpopular man who less than a year later would be defending himself with “Your president is not a crook!” on national television.

But a political convention tells a story only to the converted and to those who are politically engaged enough to actually watch the things. The ordinary people who will turn out and go to the polls and vote and win this election for one side or the other were not among the crew-cut and bejeweled crowd in Milwaukee, nor were they among the Nixon crowd in Miami Beach five decades ago.

As Democrats, we have no idea whatsoever will occur in Chicago in August, which has been the case with our party before, and will no doubt happen again in the exercise of our political lives.

Only one thing seemingly connects these quadrennial outbursts of political fervor: There will be a profusion of red, white, and blue and a modicum of embarrassing moments, and many, many opportunities to misbehave in public and in private.

I don’t know what the hooker count was in Milwaukee this week, but if our political past is as predictive of the future as it usually is, a lot of sex workers, female and male, surely made a lot of money, a good portion of which doubtlessly came from wallets of the self-identified evangelicals who support Donald Trump.

That timeless phrase, “same as it ever was,” has once again arrived to remind us that politics can change but people don’t. Everyone says that this election is the most important in our lifetimes, but I’m here to tell you that the elections of 1968 and 1972 felt that way, too. Donald Trump may be a slicker, sicker version of Richard Nixon, and his crimes may seem more serious, but our children will be saying that about another election involving yet another rancid presidential candidate 50 years from now.

We should remember another old phrase associated with hippies over a half century ago: what goes around, comes around. I, for one, have yet to see it not prove true, which should give us hope, a thing that Democrats celebrate, and Republicans disparage.

I declare tonight for all to hear that as a Democrat, I am proudly and forever hopey-changey.

Lucian K. Truscott IV

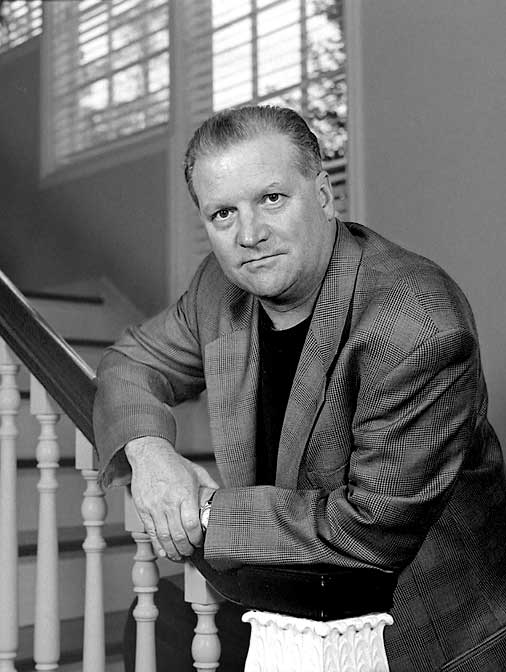

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He has covered stories such as Watergate, the Stonewall riots and wars in Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels and several unsuccessful motion pictures. He has three children, lives in rural Pennsylvania and spends his time Worrying About the State of Our Nation and madly scribbling in a so-far fruitless attempt to Make Things Better.