Republished with permission from Governing, by Carl Smith

On the morning of Sept. 5, 2023, a fire sprang to life in a redwood forest in Humboldt County, Calif. It was spotted by one of more than a thousand cameras that are part of a backcountry network monitoring the land 24 hours a day. Staff at a California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection intel center quickly alerted local firefighters, and the fire was contained to a quarter of an acre.

This outcome was the result of a decade of work by a state that has suffered the eight largest wildfires in its history in just the past five years. The cameras, trained using artificial intelligence to recognize anomalies that could be signs of wildfire, make up part of an interlinked technology network that is redefining the scope of fire prediction, prevention and response.

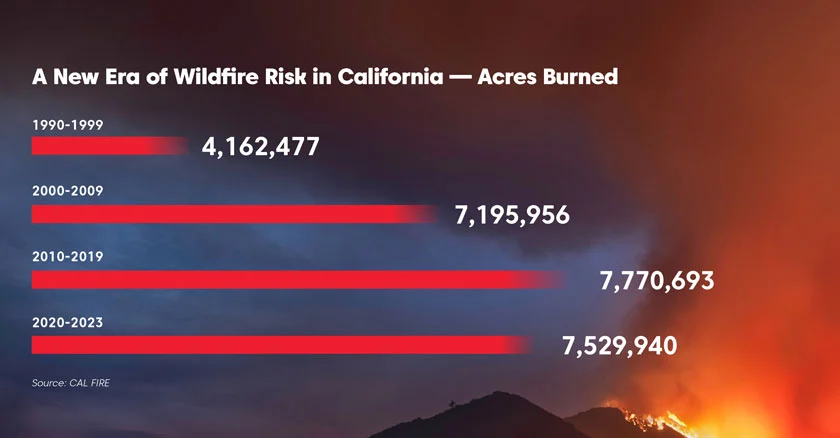

This couldn’t happen too soon. Fire events in the contiguous United States have come at triple the frequency and are four times bigger than in previous decades. The yearly number of fires has almost doubled in both the West and the East, as compared to 1984-1999. The increase was fourfold in the Great Plains. Just as scientists warn that hurricanes have become so strong that we need a new category to describe them and hundred-year floods wash over communities far more frequently, concerns are growing that bigger, stronger and repeated wildfires could become the dangerous new normal for fire activity, due to a combination of climate change, forest management practices and increasing amounts of housing near grasslands.

But advances in a wide range of technologies have created new possibilities for understanding the conditions that make fire more likely; spotting fire in its earliest stages; identifying precisely where responders need to be sent; and tracking where fires are moving. California is at the leading edge of implementing and integrating these tools, and officials are eager to share what they’re learning. “What we’re trying to do is to have data drive decisions,” says Neal Driscoll, a professor at UC San Diego’s (UCSD) Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

Utilities Help Support

Driscoll is director of ALERTCalifornia, a public safety program that draws on the skills of a multidisciplinary team and supercomputing resources at UCSD. ALERTCalifornia aims to improve the understanding of, and response to, climate-driven events in the state, which include floods, atmospheric rivers and landslides, as well as fires. In addition to UCSD experts, ALERTCalifornia has help from many partners, including other universities, scores of technology companies, electric utilities, counties, the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services, the California Natural Resources Agency and the U.S. Forest Service.

Years ago, working with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, which is known as CAL FIRE, ALERTCalifornia began using AI to train a forest-based camera network to recognize early signs of fire. There are already 1,100 high-definition cameras in place around the state and their number is growing. They scan the horizon every two minutes.

Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) helped support the initial AI work. Like other utilities in California and across the country, it has much at stake. The multibillion-dollar scale of liability for fires blamed on its equipment pushed it into bankruptcy in 2019. (It emerged the next year.) In 2021, the Dixie Fire erupted, which was the second largest in California history at a mind-boggling 1 million acres. A CAL FIRE investigation concluded it had been sparked by PG&E powerlines, which led to a $45 million penalty from utility regulators. (Other claims are still being pursued.) This isn’t just a California problem. Hawaiian Electric has acknowledged that last year’s devastating wildfire in Maui was caused by power lines, but the utility blames the scale of its impact on the actions of responders.

California’s AI project was intended to bring round-the-clock forest surveillance closer to reality. It’s too much to ask humans to pay close attention to feeds from a thousand cameras at every hour of every day. If AI could learn what kinds of anomalies in a landscape might signify fire, the network could alert staff at command centers, where experienced firefighters could interpret what it had flagged. Some of the cameras in the ALERTCalifornia network had been in place for decades. Petabytes of data (each one equivalent to a million gigabytes) had been archived and could be used in machine learning. “We could go back and say, ‘This is what smoke looks like in this image,’” Driscoll says. “We were constantly showing different attributes—smoke columns, smoke being bent over—so we could build up enough high-quality data that the AI could detect change or ignition.”

By June of last year, it was time for a pilot at six CAL FIRE 911 dispatch centers. Within two months, the AI-trained cameras had spotted 77 fires before a 911 call came in about any of them. In September, the system was implemented at all 21 dispatch centers in the state.

A NEXT-GENERATION LOOKOUT TOWER: Data and images stream into a CAL FIRE regional intel center, allowing experienced firefighters to monitor millions of acres. Carl Smith

High Tech Watchtower

Before AI, intel staff would pull up the feed from a camera at a location where a fire had been reported by an observer, analyze what they saw and respond as appropriate. Now this process begins with their data system generating text messages, robocalls and on-screen alerts to let them know AI has detected an anomaly. Cameras see about 60 miles across the landscape during the day and 120 miles at night. Analysts can raise them, rotate them and zoom in to an area that AI has flagged. If a fire is determined to be present, alerts go out to the relevant fire department that include exact GPS coordinates. Another AI tool automatically generates a simulation of how it might spread. Intel staff do simulations as well.

All relevant agencies—state, local and federal—share a common operations platform. The public can’t access this, but it can access ALERTCalifornia’s cameras. CAL FIRE maintains a public page with an interactive map of active wildfires greater than 10 acres, as well as a running tally of wildfires for the year and acres burned.

At CAL FIRE’s southern region intel office in Riverside, Battalion Chiefs Sean Landavazo and Travis Lemm are monitoring a real-time data stream that includes wind and weather, camera feeds, maps, satellite radar, internal communications, and more, displayed on multiple monitors and a huge wall-mounted LED screen. There’s no active wildfire in the region at present and the veteran firefighters are working alone in their next-generation lookout tower. There’s at least one person doing this around the clock. If a significant fire does break out, the workspaces in the room fill with federal and state analysts, coordinating response and resources according to who has jurisdiction over the affected area. The hope is that more and more fires can be detected and suppressed before they require a response on this scale. The greatest successes will be the fires no one ever hears about.

Landavazo and Lemm have both worked on hand crews and engines. Landavazo was chief in Highland, near the San Bernardino Mountains. Lemm worked the high desert. They aren’t bringing a “techy” skill set to their new assignment, but rather the operations experience necessary to understand what tech tools might be telling them. “As young firefighters, it was drilled into us to get into full dress and on the road responding within a minute,” says Landavazo. “If we could respond within a minute that could make a difference, maybe save somebody’s life. Seconds count in this job, and this is getting us to fires quicker.”

Fires Are a Fact of Life

We’re not going to be able to avoid fires altogether, any more than we can avoid earthquakes or tornadoes, says Jacquelyn Shuman of NASA’s Ames Research Center. But throughout history some communities have managed to live sustainably with it. NASA’s agencywide wildland fire management initiative is working with local, state and tribal partners to help make that possible, despite the added risks from warming. Shuman is project scientist for a program called FireSense, which is drawing on the agency’s technology and earth science expertise, including satellites and aircraft, to support those making operational decisions by improving data regarding pre-fire fuels, fire dynamics, post-fire impacts and air quality.

Past conventional wisdom was that fire growth slows at night, but hotter and drier air works against this. NASA software engineer Spencer Monheim is the technical lead for efforts to develop software that can enable drones to operate at night or during periods of extremely low visibility. They can drop water or fire retardant, or track the path of a fire in conditions that create great risks for human pilots. Ground crews, drone operators and human pilots all need to share information about their locations, however, and one of NASA’s main challenges is creating software that gives all involved the situational awareness necessary for safe airspace management.

Wildfire smoke has increased the amount of particulate matter in the air in most of the contiguous United States. Some scientists believe these releases have been enough to offset a quarter of the air quality improvements the country has achieved since 2000. These emissions are associated with health problems including lung and heart disease and weakened immune systems, but there’s no way to address them other than decreasing the number and severity of fires.

Fine particles aren’t the only thing in smoke from burning trees and vegetation. It also carries carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. A paper from UCLA scientists attracted worldwide attention with a claim that CO2 emissions from California’s 2020 wildfires negated 18 years of its greenhouse gas emission reductions from other sectors. Not everyone agrees with this disheartening conclusion, in part because it’s based on estimates of how much biomass burned. Wildfire ecologist Chad Hanson says these models assume trees burn to the ground, but field observations have found that only 2 to 5 percent of tree biomass is consumed even in severe fires. Some of the carbon released will be reabsorbed by vegetation as it regrows.

The Bill Is Coming Due

Still, it would be a mistake to see any of this as reassuring. “An average-sized fire today, about 100,000 acres, releases approximately the same amount of CO2 as 7 million cars operating continuously for a year,” says UCSD’s Driscoll. No matter how CO2 from fires stacks up against other reductions, an emission source of this magnitude must be contained when possible—not least because warming is making fires worse.

Like warming, the bill for decades of mismanagement is coming due. For millennia, Indigenous people used low-intensity cultural burns to prevent larger fires. Beyond simply clearing out fuel, they used the restorative properties of fire to maintain the health of ecosystems that tribes depended on for their survival. This ended when they were pushed off their lands. California made the practice illegal in 1911, but today it’s working with tribes to incorporate cultural burns in forest management. Prescribed burns, a modern version of this practice, can be done for similar reasons, as in a Fishlake National Forest burn in Utah intended to stimulate regrowth of aspen trees. FireSense used this event to study the efficacy of sensors for measuring moisture in soil and vegetation.

But prescribed burns can also be used simply to reduce concentrations of vegetation that can add to the intensity and spread of wildfires. More than 99 percent of prescribed burns stay within their intended boundaries, according to the Forest Service. (The practice has faced some pushback recently. In 2022, two prescribed burns in northern New Mexico grew out of control and merged, becoming the largest wildfire in the state’s history, consuming nearly 350,000 acres and displacing thousands.)

Forests are also thinned to reduce their fuel load. Hanson is part of a group of researchers who have done research using Forest Service data that shows backcountry forests that have been logged extensively burn more severely. Moreover, he says, fires are doing valuable ecological work, creating new habitats that increase the diversity of plant and animal species. “I think the moment is right for policymakers to look at this issue and re-evaluate past assumptions, because what we’ve been doing is an abysmal failure,” Hanson says. For his part, UCSD’s Driscoll thinks more data is needed before it’s clear whether too much or too little of such management is worse.

No one thinks AI or other technology alone will provide a complete solution for California’s wildfire problem. Cameras are still being trained. They can spot something that might be a fire, but it takes an experienced firefighter to evaluate what they have flagged. Sightings by firefighters and volunteers in the field and in observation towers, as well as 911 calls from citizens and pilots, remain essential.

California’s extensive AI-trained camera network is unique, but it’s not the only state using data from cameras, satellites, drones and meteorologists to monitor forest conditions and fires. Driscoll has been in conversation with fire officials in Hawaii, Wyoming, Colorado, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon, as well as others in Canada and the European Union. NASA’s tradition of technology transfer has brought game-changing technology including desktop computers, solar energy and flat-screen televisions into general use. It intends to share anything it develops to assist firefighters with states. And the private sector is developing its own technology solutions for this market. CAL FIRE and the Forest Service, along with a number of electric utilities, use a platform developed by a company called Technosylva to predict fire risk and inform mitigation decisions.

Wildfires present a use case for AI and other technologies that has existential consequences. Past models, based on historical data, have limited use in predicting fire risk, behavior and impacts under the new normal. “We have to move together, leverage resources and try to mitigate the impacts of these hazards,” Driscoll says, “because they are only going to get worse.”

Governing

Governing: The Future of States and Localities takes on the question of what state and local government looks like in a world of rapidly advancing technology. Governing is a resource for elected and appointed officials and other public leaders who are looking for smart insights and a forum to better understand and manage through this era of change.