Republished with permission from Lucian K. Truscott IV.

First, we need to talk about it. The problem, and it’s not a new one, is that certain people don’t want to talk about slavery, and we know who those people are. They are today’s followers of the so-called Lost Cause movement. This movement sprang up from the ashes of the Confederacy during Reconstruction and began with the lie that the Civil War wasn’t fought over slavery, it was fought over states rights.

Think about that for a moment. They weren’t even good at framing their cause, because to say that a war between Americans was fought over something called states rights immediately raises the question: states have a right to do what, exactly?

Well, the right that was at issue from the nation’s birth at the Constitutional Convention right through the years before the Civil War was the right to own slaves, and every statement of secession issued by every Southern state spelled out that issue in bold letters. Reading through the resolutions of secession of the southern states, there are references to the north oppressing “slave owning states.”

There are repeated references to states of the North violating the Fugitive Slave Act, which gave southern states the right to cross state borders to regain possession of slaves who had escaped their condition and fled north. There are just as many references to the issue of slavery in the territories, with at least one state singling out the issue in its own separate paragraph.

The state of Georgia, in the concluding paragraph of its declaration of secession attacking the tyranny of northern states, put it in dollars and cents:

“Because by their [northern states] declared principles and policy they have outlawed $3,000,000,000 of our property in the common territories of the Union; put it under the ban of the Republic in the States where it exists and out of the protection of Federal law everywhere; because they give sanctuary to thieves and incendiaries who assail it to the whole extent of their power, in spite of their most solemn obligations and covenants; because their avowed purpose is to subvert our society and subject us not only to the loss of our property but the destruction of ourselves, our wives, and our children, and the desolation of our homes, our altars, and our firesides.”

The word slave or slavery is not to be found in that long concluding paragraph. Even then, they were attempting to bury with rhetoric the real reason they were seceding from the Union.

How to talk about slavery has been thrust anew into the national conversation by one of the Republican candidates for president, Ron DeSantis of Florida, whose state recently passed a law changing how the subject of slavery will be taught in schools in the state. Among its incredible tenets is the idea that slaves “benefitted” from the skills they were taught as slaves. DeSantis himself, in a recent statement, defended his state’s minimizing of the horrors of slavery by giving an example of a slave, who having learned blacksmithing, was able to put that skill to use later in life when he was free.

The problem with DeSantis and his state’s treatment of slavery in its education standards is the abject ignorance shown by DeSantis and others, including puppets on Fox News endorsing Florida’s new standards. The so-called slave codes of Southern states, including Florida, made it illegal to teach slaves how to read and write and add and subtract; forbade slaves from traveling without a permit from the slave’s owner; outlawed slaves from buying or selling things; allowed slaves to be searched at any time; gave marriages between slaves no legal standing and disallowed birth certificates to children born of enslaved women.

It is not possible to do the proper work of blacksmithing—or carpentry, or sewing, or cooking, or masonry, or manufacturing wooden boards by sawmilling, or nailery, or any number of other jobs slaves were made to do—without teaching them to make measurements, that is, to add and subtract and make the results of such math available to others, which is to say, write them down and have other slaves doing the same work be able to read them.

As I have written many times before in this space and others, the skilled labor of slaves built the South and its plantations and homes and state capitals and places of business owned by whites. In a recent column, I wrote about how Thomas Jefferson’s slave John Hemings, the brother of Sally Hemings who gave birth to six of Jefferson’s children, built fine furniture which can be seen at Monticello and did much of the fine woodworking at Poplar Forest, Jefferson’s summer home. There is a trove of letters between John Hemings and his master, Thomas Jefferson, discussing designs and measurements and construction of the work Hemings did. If DeSantis were to peek even just a little teeny bit into the history of slavery in Florida, he would find evidence of slave owners who taught their slaves how to read and write and add and subtract in violation of the slave codes they either wrote or voted for.

So, it wasn’t just slaves learning skills they could put to use later in life as freedmen or freedwomen, thus justifying slavery and promoting the lie that slave owners were good to their slaves and slavery itself was thus beneficial to them. What of the enslaved people who were born into slavery and died as slaves? How did they benefit from what was so kindly and generously done for them by their owners?

It is all a great fiction, of course. Florida and other states planning to frame their education systems so that they sanitize slavery, and Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, and the civil rights struggles to attain, among other basic rights, the right to vote, don’t want to teach history. They are whitewashing it. They want to teach a kinder, gentler version of the Lost Cause. And it is happening beyond the boundaries of the classroom.

One of my readers sent me a Washington Post article from 2019 about the push-back historians and docents at places like Monticello and Montpelier and Mount Vernon are getting from visitors who object to the teaching about slave life at those venerable plantations. The Post recounts a story from a tour guide at Monticello who was explaining how slaves had terraced the hillside below Mulberry Row and grew vegetables to be served to Thomas Jefferson and his family when they ate meals that were cooked by slaves. “Why are you talking about that?” asked a woman on the tour. “You should be talking about the plants.” A visitor on a tour of a plantation in South Carolina objected to the history of slave life that was given by the tour guide. “I didn’t come to hear a lecture on how the white people treated slaves,” the tourist complained.

That was four years ago. Can you imagine what it’s like to lead a tour at Monticello or one of the other southern plantations today, with the Republican Party basically running on the proposition that we should just sweep all those nasty stories about slavery into a bin somewhere and forget about them.

One of the strongest memories I have about the first weekend I took 70 or so of my Hemings cousins to the Jefferson family reunion at Monticello is what happened just as I was leaving what the people who work there call the “top of the mountain” on Saturday evening after an army of reporters and television crews from around the world had filmed the first time that Jefferson’s Black descendants had attended the family reunion. The man who was in charge of the groundskeepers at Monticello approached me as I was walking away from the lawn where the reunion had taken place. “Just a minute,” he called out to me. I stopped. “Do you know what you’ve done?” he asked me. Responding to his obvious hostility, I answered, “Why don’t you tell me.”

“You’ve ruined everything,” he said. “Now it’s all going to be different up here. You ruined it.”

That was in May of 1999. I’ve ruined it for that man and others like him for nearly 25 years now, and I intend to keep on ruining it by talking about the history of slavery as loudly and for as long as I can. I’ll be buried in the graveyard at Monticello one day, and if you visit there after my death, you’ll be able to hear me still, in the words on my headstone.

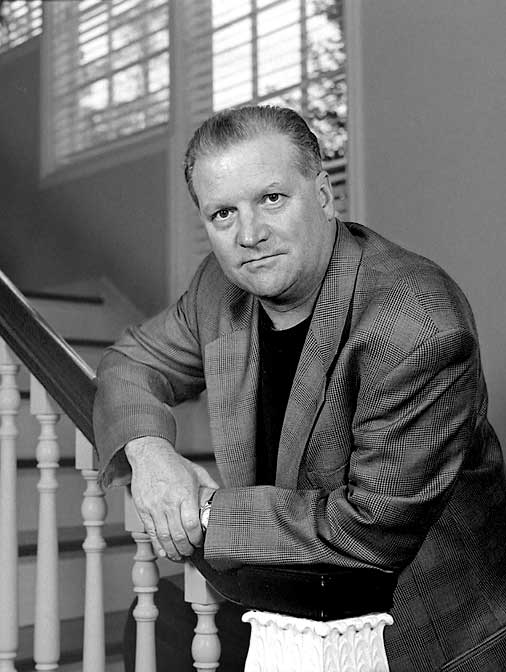

Lucian K. Truscott IV

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He has covered stories such as Watergate, the Stonewall riots and wars in Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels and several unsuccessful motion pictures. He has three children, lives in rural Pennsylvania and spends his time Worrying About the State of Our Nation and madly scribbling in a so-far fruitless attempt to Make Things Better.