Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that “all men are created equal.”

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure.

We are met on a great battle field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it, as a final resting place for those who died here, that the nation might live.

This we may, in all propriety do. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow, this ground—The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have hallowed it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here; while it can never forget what they did here.

It is rather for us, the living, we here be dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that, from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here, gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people by the people for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

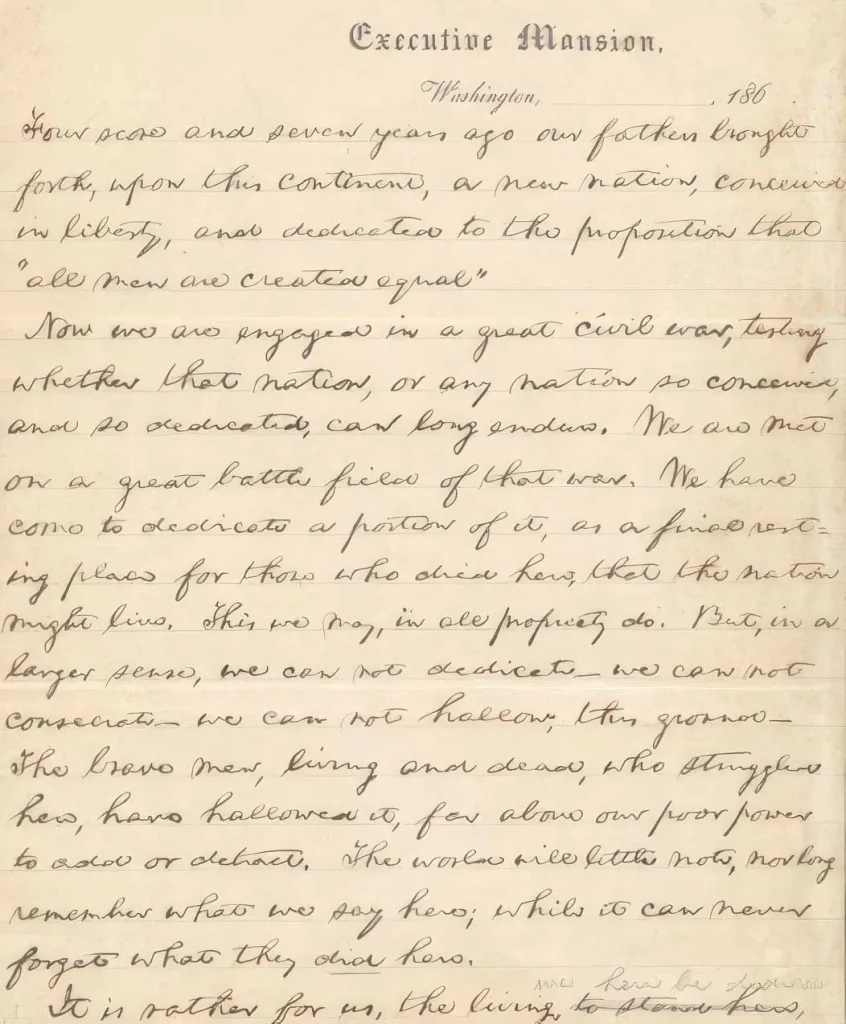

Here’s information from the Library of Congress related to the Gettysburg Address:

Abraham Lincoln was the second speaker on November 19, 1863, at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg (in Pennsylvania). Lincoln was preceded on the podium by the famed orator Edward Everett, who spoke to the crowd for two hours. Lincoln followed with his now immortal Gettysburg Address …

Of the five known manuscript copies of the Gettysburg Address, the Library of Congress has two. President Lincoln gave one of these to each of his two private secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay. The other three copies of the Address were written by Lincoln for charitable purposes well after November 19. The copy for Edward Everett, the orator who spoke at Gettysburg for two hours prior to Lincoln, is at the Illinois State Historical Library in Springfield; the Bancroft copy, requested by historian George Bancroft, is at Cornell University in New York; the Bliss copy was made for Colonel Alexander Bliss, Bancroft’s stepson, and is now in the Lincoln Room of the White House.

Republished with permission from Florida Phoenix, by Diane Rado

Florida Phoenix

The Phoenix is a nonprofit news site that’s free of advertising and free to readers. We cover state government and politics with a staff of five journalists located at the Florida Press Center in downtown Tallahassee.