Republished with permission from Lucian K. Truscott IV

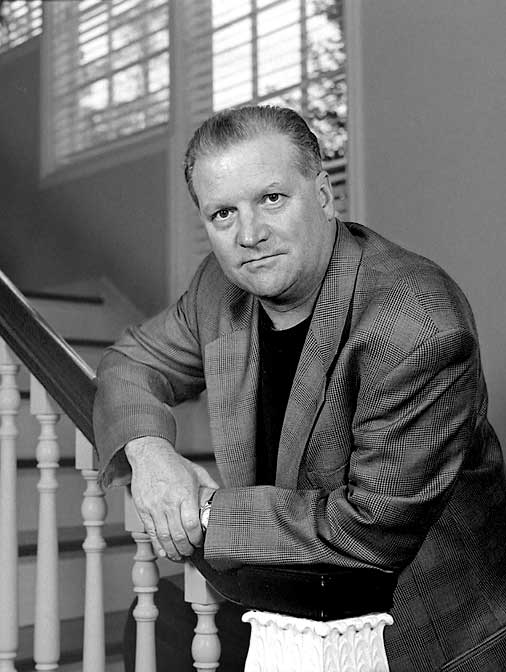

The photo above is of my grandfather, Gen. Lucian K. Truscott Jr., giving the Memorial Day address at the Anzio/Nettuno cemetery on May 31, 1945. As you can see in the photo, the microphone stand is to his left. He had stepped away from the microphone and had turned to address the fallen soldiers buried in the cemetery. He spoke unaided by amplification, because he didn’t need it. The men and women he addressed were dead, many of them killed when he was their commander at Anzio. Stars and Stripes reported on the remarks he made to assembled dignitaries before turning to address the dead: “All over the world our soldiers sleep beneath the crosses. It is a challenge to us—all allied nations—to ensure that they do not and have not died in vain.”

We must turn to the famous Army cartoonist Bill Mauldin, who witnessed the ceremony, and wrote about it in his memoir “The Brass Ring” to hear what happened next.

“There were about twenty thousand American graves. Families hadn’t started digging up the bodies and bringing them home,” Mauldin wrote in his 1971 memoir.

“Before the stand were spectator benches, with a number of camp chairs down front for VIPs, including several members of the Senate Armed Services Committee. When Truscott spoke he turned away from the visitors and addressed himself to the corpses he had commanded here. It was the most moving gesture I ever saw. It came from a hard-boiled old man who was incapable of planned dramatics,” Mauldin wrote.

“The general’s remarks were brief and extemporaneous. He apologized to the dead men for their presence here. He said everybody tells leaders it is not their fault that men get killed in war, but that every leader knows in his heart this is not altogether true.

“He said he hoped anybody here through any mistake of his would forgive him, but he realized that was asking a hell of a lot under the circumstances. He would not speak about the glorious dead because he didn’t see much glory in getting killed if you were in your late teens or early twenties. He promised that if in the future he ran into anybody, especially old men, who thought death in battle was glorious, he would straighten them out. He said he thought that was the least he could do.”

The “hard-boiled old man” Mauldin describes was 50 years old. Bill Mauldin was 23.

Grandpa had a great feel for the men and women who served under him. He was known among war correspondents as “the soldier’s soldier” because of his frequent appearances at the front lines. He was taciturn and unshowy. In the photograph above, he is wearing the standard Army duty uniform of the time: tan gabardine trousers, known as “pinks,” his Eisenhower jacket, a tan uniform shirt and a tie.

In his memoir, “Command Missions,” Grandpa expressed his admiration for the soldiers he had led into battle in typically direct and frank language:

“The American soldier did not like war. He dreaded the uncertainty, danger, and hardship. He was rather resentful of military discipline and its interference with his individual liberties. He hated the monotony of military training and the physical effort it required. When asked why he was fighting, the answer was as often as not, “because I have to.” He may not have known just why he was in Africa, or Italy, or elsewhere, but he appreciated well enough why he was fighting. War had been forced on the country at Pearl Harbor; like others, he had to do his part toward winning it. Disliking war, discipline, training, discomfort, and hardship, the American soldier accepted them philosophically as aspects of a disagreeable task to which he applied his native ingenuity and resourcefulness. The American soldier demonstrated that, properly equipped, trained, and led, he has no superior among all the armies of the world.”

On this day, we pay tribute to all the American soldiers who died in this nation’s wars defending the Constitution to which they had pledged their lives. They will never be forgotten.

Lucian K. Truscott IV

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He has covered stories such as Watergate, the Stonewall riots and wars in Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels and several unsuccessful motion pictures. He has three children, lives in rural Pennsylvania and spends his time Worrying About the State of Our Nation and madly scribbling in a so-far fruitless attempt to Make Things Better.