Republished with permission from Governing Magazine, by Carl Smith

In Brief:

- The Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits for tax-exempt entities that can repay costs for clean energy projects.

- The program, which has not attracted the same level of attention as credits for private investment, is open to an unlimited number of applicants.

- The process for obtaining these credits is unlike that of any previous program, and online resources have recently been published to make it easier to navigate.

In the two years since the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was signed into law, IRA tax credits for private-sector clean energy projects have been widely celebrated and estimates of the investment they have sparked range from $125 billion to $265 billion. Credits that repay energy investments by public agencies and other tax-exempt organizations have received much less attention, but a new online tool aims to redress the imbalance.

Under the “direct pay” program, the IRS will reimburse public agencies, tribal governments, nonprofits, churches, schools or other tax-exempt entities for projects involving clean energy technologies such as solar, wind and geothermal heat pumps. It also encompasses EV charging stations, electric fleet vehicles and battery storage.

The rate of reimbursement can be as high as 70 percent, and the equity imperatives woven throughout the IRA set the stage for organizations that serve disadvantaged populations to qualify for bigger paybacks. The paradox is that they are less likely to have capacity to research the direct pay program and work out how to benefit from it. The Clean Energy Tax Navigator, developed by Lawyers for Good Government (L4GG), was designed primarily for such users.

“The whole point is to level the playing field,” says Jillian Blanchard, director of L4GG’s climate change and environmental justice program. There is no limit to the number of entities that can apply for the credits or the number of projects for which any one applicant could receive them. The IRA authorizes the program through 2032.

The historic dimensions of this federal funding haven’t sunk in for many jurisdictions. “We call this a crisis of opportunity,” Blanchard says. “We want to make sure people don’t miss out.”

There is an added urgency to taking advantage of the opportunity as the general election approaches. By one estimate, as of May 2024, only 15 percent of the IRA has been spent. The balance could be reallocated to other priorities by another administration.

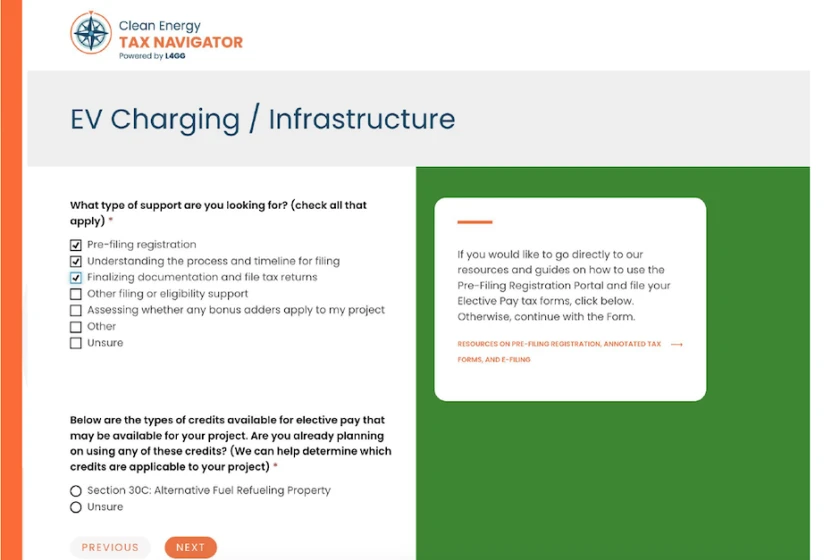

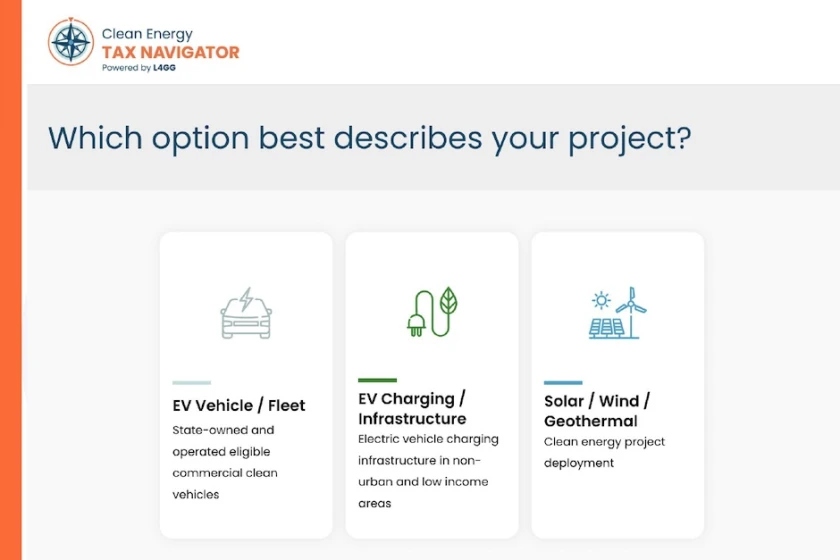

An opening screen at the Clean Energy Tax Navigator is the first step in a guided process of determine eligibility, connecting to resources and preparing the necessary forms. (L4GG)

Filling a Support Gap

The IRS doesn’t offer support to those interested in the direct pay program, but the only way a tax-exempt entity can receive credits is by pre-registering a project with the agency. Payment comes after an organization files tax forms claiming credits and the IRS verifies pre-registration. This is unlike any previous process.

Even before taking this on, an applicant needs to be certain the work it has in mind qualifies for credits and understand what it takes to receive the largest possible payback. The navigator walks users through both of these processes through a series of questions and prompts.

The credits are potentially transformative for rural communities or communities of color affected by disinvestment, says LiJia Gong, policy and legal director at advocacy organization Local Progress.

The base credit is 6 percent of the total cost of an energy project. This goes up to 30 percent if it meets the IRA’s prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements. Another 10 to 20 percent is available through a bonus credit for low-income communities. There’s 10 percent more for projects in historical energy communities, such as those where coal mines or coal-fired power plants have been closed, and another 10 percent if a project uses specified amounts of domestically produced materials and products. (Credits are also available for energy generation, with different metrics but comparable payback.)

By capturing all of these credits, a disadvantaged community could recoup up to 70 percent of its investment. The Department of Energy has created mapping tools that identify qualifying energy and low-income communities, and these are integrated in the navigator. L4GG offers pro bono legal support through the navigator, prioritized for applicants from at-risk jurisdictions.

Getting to First Base

Direct pay credits (also called “elective pay”) are available to projects completed in the tax year for which they are claimed. They don’t provide financing; they reimburse expenditures. They are a windfall for work where funding is already in place, but they can also be a catalyst for new funding.

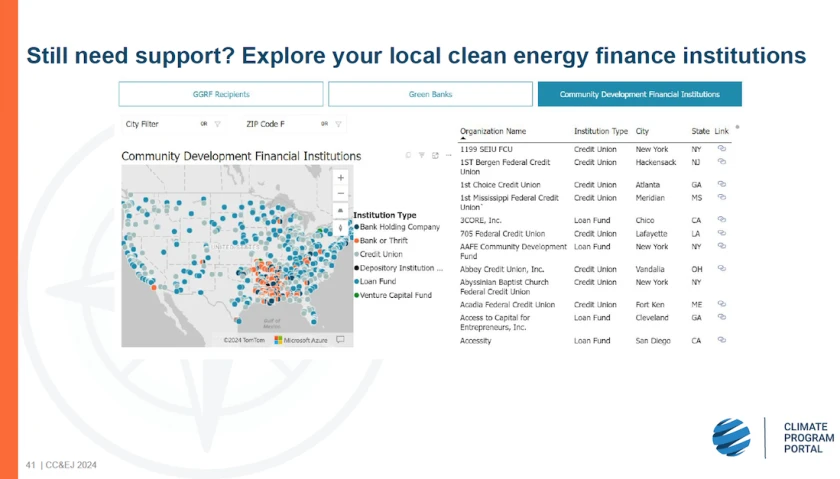

In addition to its grant programs, the IRA includes $27 billion for a Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund which supports green banks and community development finance institutions. “I encourage anybody to see what kinds of institutions are in their state or region,” says Annabelle Rosser, a research analyst at Atlas Public Policy.

The Project Finance Hub created by Atlas Public Policy as part of its Climate Program Portal, linked to the Clean Energy Tax Navigator, is a guide to funding sources for energy projects.

The hub includes a mapped directory of these institutions, as well as a dashboard of federal opportunities for which RFPs are still open. All of this is provided at no cost to tax-exempt organizations (as is the Clean Energy Tax Navigator). Technical assistance, including pro bono legal advice, is also available. The Climate Program Portal also tracks investments from the IRA and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

The finance hub and the navigator are meant to work in tandem, Rosser says, to make it easier for not-for-profit and public agencies to get their bearings in the new landscape of funding the IRA has created. Local and state governments can play a vital role in getting the word out about these resources to tax-exempt organizations, Gong says. Over the long term, savings from assets such as solar panels can support the work of schools, churches or nonprofits.

The Project Finance Hub can direct users to funding sources including the federal government, green banks and community development finance institutions. (Atlas Public Policy)

A Bump in the Road?

Direct pay credits are now integrated into federal tax code, and the only way they could be eliminated is by new legislation. Some in Congress have attempted to make significant cuts in IRA appropriations. None have prevailed, and the election cycle is too volatile to predict what might happen after November.

“We don’t want to be overconfident, but we do think it’s going to be fairly difficult to get Congress to overturn the Inflation Reduction Act,” Blanchard says. “Business models have been crafted around these credits.” Moreover, L4GG is working with numerous cities in red states that are taking advantage of them.

The direct credit program is authorized through 2032, and Blanchard thinks it’s likely to be renewed. As she sees it, the question isn’t whether tax-exempt entities should learn how to use this program. “It’s when you decide you’re going to take this essentially free money for clean energy practice you’re already doing,” says Blanchard. “We want to make it as painless as possible, recognizing that it’s complicated but totally doable.”

Governing

Governing: The Future of States and Localities takes on the question of what state and local government looks like in a world of rapidly advancing technology. Governing is a resource for elected and appointed officials and other public leaders who are looking for smart insights and a forum to better understand and manage through this era of change.