Republished with permission from Lucian K. Truscott IV

They are glorious, frightening beasts, bristling with guns large and small and these days, with a target acquisition and aiming technology suite that all but guarantees one-shot-one-kill in a tank-on-tank battle. I’m talking of the Army’s main battle tank, the M1 Abrams. It’s a big thing—26 feet long, 12 feet wide and 8 feet tall—70 tons of steel and composite armor, armed with a 120 mm main gun, a .50 caliber machine gun, and two M240 7.62 mm machine guns. The standard ammunition load is 40 rounds for the main gun, 900 rounds of .50 caliber ammunition, and 10,000 rounds for the M240s. As massive as they are, Abrams tanks are capable of going 45 miles per hour and placing accurate fire with the main gun while in motion.

You would think with that much firepower and size and speed that a tank like the Abrams would be nearly invulnerable, but they aren’t. In fact, according to Eurasian Times, three of the 31 Abrams tanks we sent to Ukraine last year have been destroyed in a single week. Advances in handheld anti-tank rockets used by infantry soldiers and drone warfare have exposed the vulnerability of U.S. Abrams, British Challenger and German Leopard main battle tanks on the battlefield. The fight is exceptionally lop-sided.

One Abrams tank costs about $24 million to manufacture. It cost millions of dollars to ship Abrams tanks to Ukraine and tens of thousands more to train Ukrainian soldiers to use them. Manufacturing and deployment costs for Challenger and Leopard tanks are similar. One of the Abrams tanks was apparently disabled by a shoulder-fired RPG-7 rocket before it was destroyed by a missile fired by a drone. Another Abrams was damaged by a mine and then knocked out by an anti-tank guided missile. An anti-tank mine costs several hundred dollars. An RPG-7 warhead costs less than $100.

It just doesn’t make sense to spend tens of millions of dollars on a weapon that can be disabled by munitions costing hundreds of dollars and knocked out by anti-tank missiles costing a few thousand.

There are large problems in the way tanks have been used by Ukraine in this war. The first is that in order for tanks to be effective, they must be deployed by the hundreds, not dozens, but that is the fault of the U.S. and NATO, not Ukraine. The second is that while the United States was dithering about whether to send Abrams tanks to Ukraine, and then when, Russia was building an elaborate anti-tank web of defenses along front lines that have stabilized in this war. They dug anti-tank trenches and scattered fields with anti-tank and anti-personnel mines making it virtually impossible for Ukraine to mount an offensive using tanks and infantry, the way they would be ordinarily deployed.

But nothing can be said to be ordinary about the way tanks have been used by either side in this war. Russia has reportedly lost thousands of tanks in the same way Ukraine lost the three Abrams tanks recently—they were disabled by RPGs and then “killed” using hand-held Javelin anti-tank missiles supplied by the U.S. An entirely new way of attacking tanks has emerged over the last few years. Helicopter drones are flown over tanks and used to drop small bombs or grenades that damage the tank enough to stop it, and then it’s attacked from the ground with anti-tank missiles.

This has engendered a new tank-defense arms race, whereby steel “birdcages” are constructed over the tops and along the sides of tanks so that RPG rounds or grenades dropped by drones explode more or less harmlessly upon hitting the birdcages, rather than penetrating the comparatively thin armor of a tank’s turret. This is an example of such cages mounted on a Ukrainian mobile howitzer:

None of this stuff existed during the first Gulf war, the last time that tanks were used in battle in the way they were designed to be used—in mass attacks across flat ground backed by infantry and armored personnel carriers. At that time, the big advances in anti-tank warfare were Air Force fighters equipped with anti-tank missiles, including the A-10 “Warthog” that was equipped with a Gatling-style rotary cannon firing armor-piercing shells as well as wing-mounted anti-tank missiles. Anti-tank weapons fired on the ground by infantry were wire-guided, and the soldiers operating the weapon had to guide the missile to its target, leaving them vulnerable to counter-fire from tanks and infantry.

All that is old technology, but the new technology on the battlefield has galloped past even the latest and greatest tanks any army can put in the field, like the Abrams. The Pentagon has reportedly shelved plans to produce a new main battle tank that would replace the Abrams, probably because of all the new challenges tanks have faced during the war in Ukraine. There is a lot of speculation in publications like Popular Mechanics that follow weapons development that the next generation of tank-like weapons systems will be robotic, and of course the idea of AI-driven systems is being thrown around. Whatever the Pentagon decides, it will take at least a decade or more to design and test a new weapons system as important and expensive as whatever replacement will be that they come up with for the main battle tank.

The problem faced by Western armies and the armies they may face in the future is the same: it turns out that old-tech warfare like that deployed by Russia defensively along its front lines actually works and works well. How do you fight an enemy that can use simple stuff like earth moving equipment to dig trenches and thousands of inexpensive mines backed up by drones and relatively inexpensive artillery and guided and unguided missiles?

The U.S. military is facing similar dilemmas on the sea and in the air. We have a huge navy and air force comprised of ships and aircraft that are enormously expensive. The threats they face are much less expensive, as we are learning in the Red Sea, where Houthi rebels are using drones to attack civilian shipping and U.S. naval vessels. To put it bluntly, drones cost a lot less than naval destroyers and aircraft carriers. Even the anti-ship ground-fired missiles being supplied to the Houthis by Iran are far cheaper to make than a destroyer that takes a crew of hundreds, or even thousands as in the case of aircraft carriers, to operate.

The other quandary faced by Ukraine has been Russia’s willingness to use old-fashioned tactics like human wave assaults. That was something done by the Chinese in Korea, but I don’t think mass human assaults have been used since then in the way Russia has been willing to sacrifice bodies to gain ground as they have in Bakhmut and Avdiivka. In both battles, Russian losses were in the thousands while Ukraine’s were in the hundreds, but Russia “won” those utterly destroyed towns.

Which raises a question which has been asked since wars began thousands of years ago: What does the “winner” intend to do with a place they have completely destroyed in the process of “winning?” Ukraine has been one of the world’s breadbaskets with thousands of square miles of agricultural lands growing tens of thousands of tons of grains used to feed millions. What is going to happen to all those fields that can no longer be farmed because of tens of thousands of deadly mines? What of industrial towns like Avdiivka, flattened, its citizens gone, its way of life destroyed?

The extent to which humanity is dependent on the kindness of strangers is being shown every day in Ukraine, where neighbor has attacked neighbor without warning, or seemingly, any sort of sane goal in mind. It turns out that simply being uncivilized is still an effective strategy in a conventional war like the war Russia has chosen to wage on Ukraine.

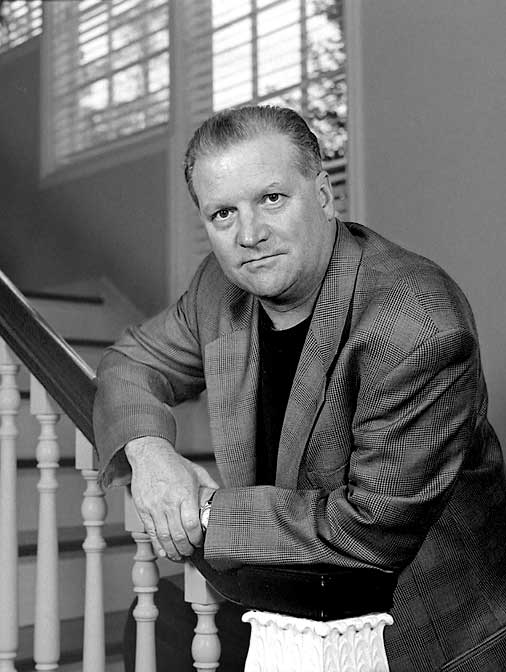

Lucian K. Truscott IV

Lucian K. Truscott IV, a graduate of West Point, has had a 50-year career as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter. He has covered stories such as Watergate, the Stonewall riots and wars in Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan. He is also the author of five bestselling novels and several unsuccessful motion pictures. He has three children, lives in rural Pennsylvania and spends his time Worrying About the State of Our Nation and madly scribbling in a so-far fruitless attempt to Make Things Better.