Republished with permission from Yale Climate Connections, by

Activists and groups that oppose offshore wind energy have hit upon a new theme to recruit environmentally minded people for their campaign. They are linking offshore wind development to a sight and a smell that no one likes: a rotting humpback whale carcass washed up on a beach or bobbing with the current as seagulls pick at its flesh.

Despite a lack of scientific evidence, they have blamed a recent spike in whale deaths on exploration devices that use sonar to seek wind turbine sites. Experts are unconvinced, but wind opponents, some with the help of funds from fossil fuel industry interests, have stoked more opposition to wind power among some residents and politicians in seaside communities. Tucker Carlson and other media personalities have also fanned the flames.

In a three-month period beginning in November 2022, 23 whales were found dead along the Eastern Seaboard, many in New Jersey and New York where some coastal residents were already opposed to the offshore wind farms—and were quick to link the deaths to offshore wind farm surveying and construction. Residents of some coastal communities received letters alleging that offshore wind projects would damage the local economy and environment, and a wave of disinformation campaigns targeted social media users.

“If you find yourself caught in one of these Facebook networks where you’re only getting a very specifically filtered barrage of misinformation and pseudoscience, pretty soon you’re way down the rabbit hole, and it’s very hard to pull people back,” said Peter Sinclair, an environmentalist and former contributor to Yale Climate Connections who has reported on misinformation campaigns targeting renewable energy. He noted that the decimation of local newspaper staff has left many people in news deserts, making them more susceptible to misinformation on social media platforms.

Experts who have actually studied the issue note that the vessels exploring for wind developers are heavily regulated and must watch out for marine mammals as well as refrain from using sonar until the animals leave the vicinity. Also, they note that the sonar used by the wind industry is much less powerful than that used by vessels exploring for offshore oil and gas, which is known to harm and even kill marine mammals.

“It is just dumb,” said Andrew Read, a professor of marine biology and director of Duke Marine Lab at Duke University in Beaufort, North Carolina. Read has been studying marine mammals for decades.

“There is not a lot of percussive energy in those types of surveys,” he said of wind exploration.

Read compared the sounds emitted during offshore wind surveying to the sound of a fan in a room, and he said that if the technology used to survey the ocean floor could cause damage to a mammal, it wouldn’t be humpbacks that would be vulnerable. It would be species like harbor porpoises that are more sensitive to the sonar frequency used to survey the seafloor and have been observed avoiding noisy areas.

So what is actually killing whales? Boats and fishing.

Since 2016, 208 humpback whales have been found either dead or stranded along shores stretching from Maine to Florida.

Scientists specializing in marine life believe that there are a number of factors involved in the latest cluster of deaths among humpback whales. First, the humpback whale population has grown, thanks to a moratorium on commercial whaling.

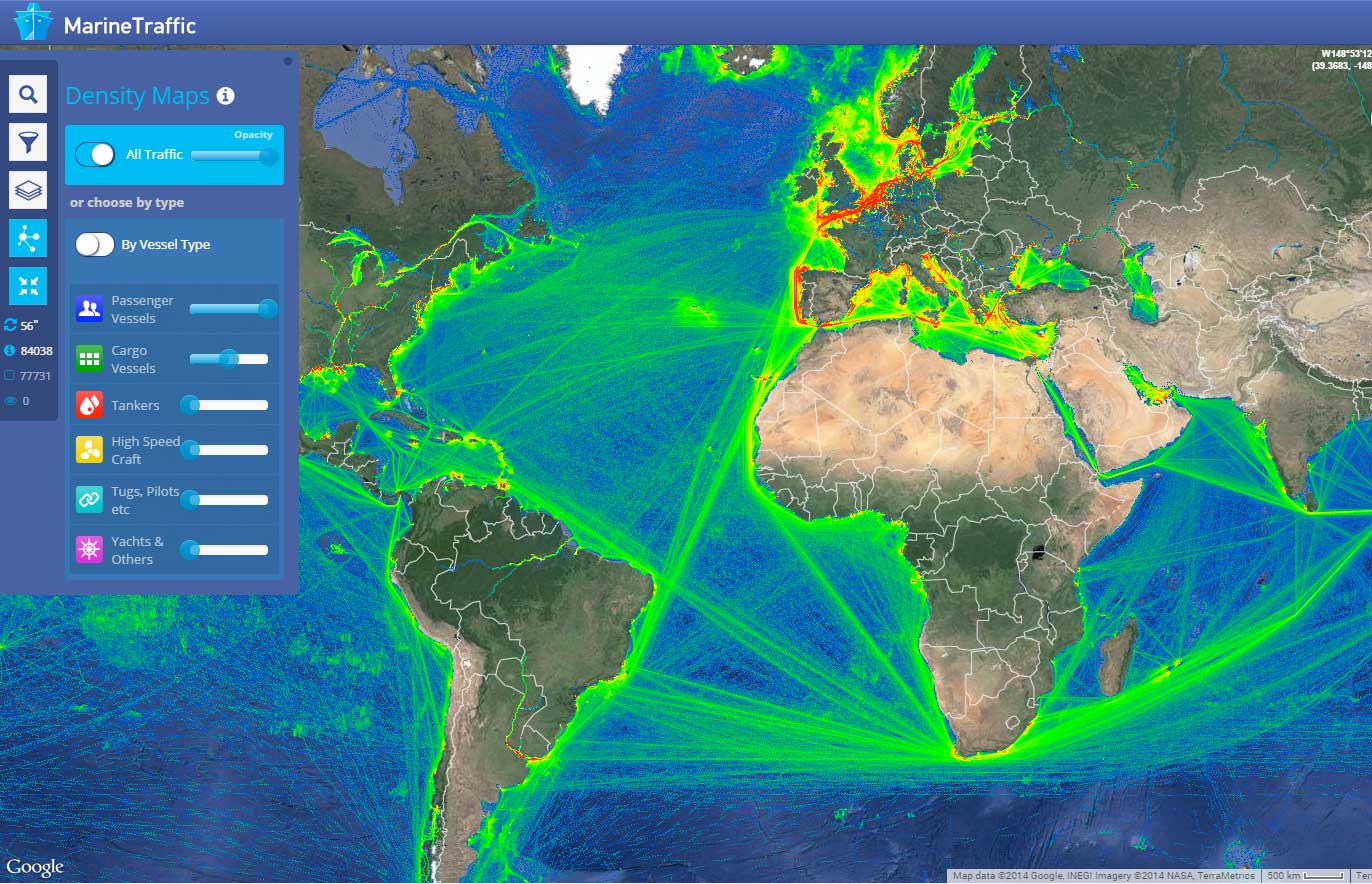

On top of that, the volume of cargo transported by ships more than doubled, from four to nearly 10.7 billion tons, globally between 1990 and 2021.

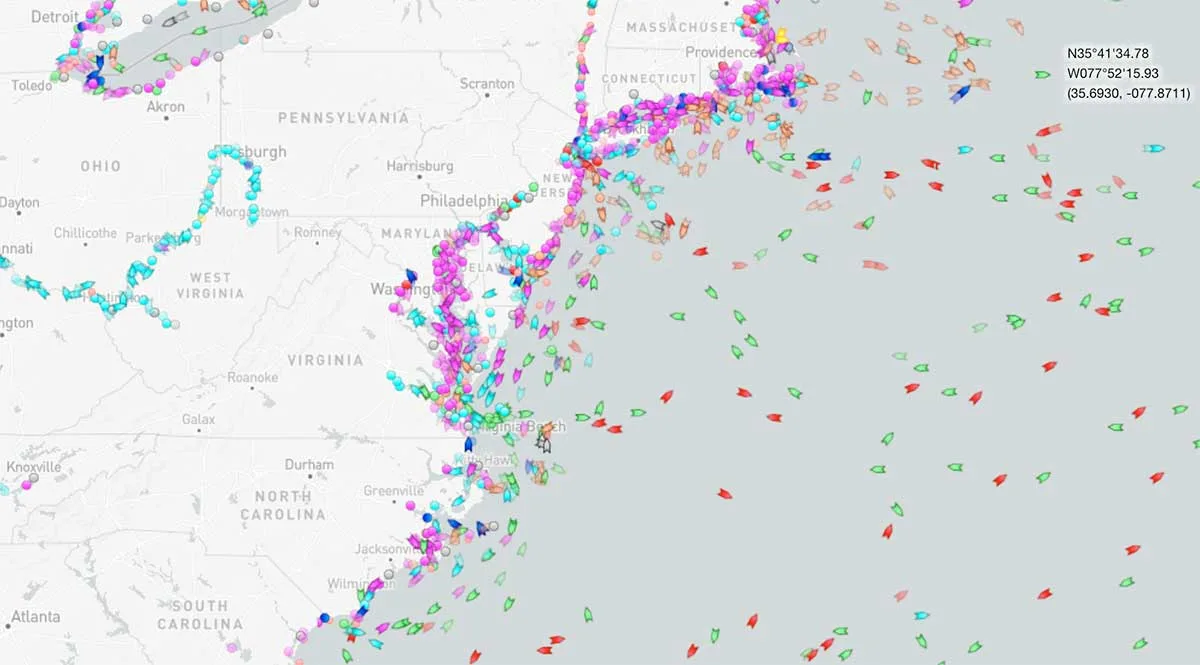

Tony Bessinger, a boat captain, has worked since 2012 for the Rhode Island Fast Ferry, which was contracted to bring workers to and from the Block Island wind farm. “I think that people have never really understood exactly how much shipping there is,” he said.

“People don’t realize that Narragansett Bay is one of the busiest car carrier ports in the U.S,” he said. “So there’s an immense amount of traffic out there that we’ll never see because it’s just out of sight of land.”

Marine traffic along the Eastern Seaboard on September 18th, 2023. (Image credit: MarineTraffic, a ship tracking and maritime analytics provider.)

As of June 21st, 2023, partial or full necropsies—autopsies for animals—were performed on approximately half of the whales found dead at that point, which was roughly 9o whales according to NOAA Fisheries. The other whales were either too decomposed, not brought to land, or stranded on protected land and so could not be examined. They found that approximately 40% of the whales showed signs of ship strikes and/or fishing gear entanglement.

Climate change linked to carbon pollution from fossil fuel use could also be a factor because warming waters are changing migrational patterns of humpbacks. And the whales’ favorite prey, menhaden, is much more abundant now in areas highly trafficked by commercial vessels, particularly along the coast of New Jersey and New York.

Every whale that washes ashore further fuels the anti-offshore wind movement. But clusters of marine mammal deaths, known as Unusual Mortality Events, are unfortunately not uncommon. A total of 72 such events have occurred since NOAA started recording them in 1991 for species like seals, manatees, whales, and sea otters. Since 2017, 115 North Atlantic right whales have been found injured, ill, or deceased, largely as a result of entanglements or vessel strikes. Their population is estimated at fewer than 350 individuals globally.

“We know that climate change is changing the ecosystem. We don’t know if wind farms are,” said Drew Carey, vice president of the Americas at Venterra Group, a company that provides offshore wind companies with support services including surveying and analysis technologies. “But if we don’t build a couple, we won’t really find out, and if we don’t build them, climate change will continue.”

Before his current position, Carey co-founded Inspire, later purchased by Venterra, a Rhode Island company that analyzes and surveys the seabed for underwater projects, including companies like Ørsted U.S. Offshore Wind.

“There’s a really big distinction between the kind of survey work that’s done for oil and gas,” Carey said. “You have to use certain kinds of acoustic energy to penetrate the seafloor and determine what the rock structure is like for thousands of feet. An offshore wind farm only needs 200 or 300 feet to put in a foundation, and so the acoustic energy required to do that is far different.”

Carey added that “the acoustic energy of any one of those beams is exactly the same as the fish finders used by every single fishing vessel, commercial or recreational.”

Due to the increase in whale deaths and the precarious situation of the North Atlantic right whale, NOAA is proposing a speed reduction zone along the Eastern Seaboard annually from November to April to prevent collisions. Many commercial and recreational fishermen oppose this potential solution, which would require boats of 35 feet or more to reduce their speed to 10 knots or approximately 11 mph in this zone. It would not affect offshore wind surveying vessels, which generally travel at or below this speed.

“Grassroots” organizations backed by not-so-green donors

Despite the scientific evidence, some concerned residents have joined “grassroots” organizations to fight offshore wind developments, which are a big part of President Joe Biden’s push to wean the U.S. economy from dependence on fossil fuels and get emissions to net-zero by 2050.

Donations to some of these organizations can be linked back to lobbyists and businessmen with connections to gas, oil, and nuclear interests. For example, the American Coalition for Ocean Protection, which is helping to fund anti-wind groups, is a project started by the Caesar Rodney Institute, a Delaware-based think tank whose funders include a fossil fuel trade group that has multiple oil executives on its board. Its director, David Stevenson, was on former President Donald Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency’s transition team.

The coalition set up a legal fund for residents to sue offshore wind projects. A group called Nantucket Residents Against Wind Turbines, whose president denies that the group is associated with the fossil industry, recently sued unsuccessfully to overturn the environmental review of the Vineyard Wind project, alleging that the review did not adequately account for potential harm to the North Atlantic right whale. The case was eventually dismissed by the judge, but it generated a lot of media attention.

Wind opponents believe it all adds up

Mike Dean of Middletown, New Jersey, has lived on the Jersey Shore all his life. He originally was concerned about the potential economic impacts of offshore wind farms along the coastline on tourism, real estate values, and commercial fishing. Then the whales started washing up.

He was not convinced by federal and scientific organizations, who say there is no evidence connecting the recent whale deaths to surveying activity. “I mean, a dead whale is evidence,” he said. “It’s not conclusive, but it’s evidence.”

Bonnie Brady lives in Montauk, New York, with her husband, a fisherman, and is well known in the fishing industry as a staunch opponent of offshore wind. “Who goes to the beach to look at an industrial power plant?” she said during a recent interview. Brady has a plethora of problems with offshore wind, from their possible effects on phytoplankton production to the loss of fishing grounds, and she is convinced that the whales are dying because of offshore wind surveying.

Some opponents have pointed to offshore wind companies “paying off” scientific organizations to promote offshore wind. It’s true that money has been given to organizations for continued study of the potential effects of offshore wind turbines on marine life. Both the donors and recipients are disclosed on the websites of these organizations.

That can’t be said for organizations like the Caesar Rodney Institute, which does not make public many of the organizations or individuals funding it. (We know who some of the major funders are through separate tax filings by the donor organizations.)

Ørsted, developer of the Block Island wind farm, defended its contributions to organizations such as the Mystic Aquarium in Connecticut, which supports offshore wind development. The company said its funding “is for independent research activities and the creation of educational exhibits and programming— not promotion. Our intent with these research partnerships is to better inform the industry’s clean energy development efforts while protecting marine environments for the future,” it said by email.

Ørsted also noted that it has partnered to fund an app called WhaleAlert that uses real-time whale presence data so that mariners can avoid areas where whales are.

What the science shows

Michael Moore, a senior scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, who has been studying the ever-dwindling North Atlantic right whale for decades, said there is no evidence that offshore wind survey vessels are causing the spike in whale deaths.

“There really isn’t an obvious path as to how these bottom survey site characteristic systems would cause the kind of damage that is being claimed,” he said, adding that an increase in ship traffic to and from offshore wind sites could cause an increased risk in vessel collision, “but it’s an incremental one, and it’s not what’s been said.”

Moore said one thing he will watch as more wind projects come online is whether potential changes to ocean currents affect phytoplankton and zooplankton, the microscopic plants and animals that live in the ocean.

What the experts can agree on is that there is no evidence that wind surveying activity harms marine life. The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management has regulations in place to ensure marine mammal safety, including that operators must establish an “acoustic exclusion zone” for geophysical surveys, that is to say, a zone that is clear of any marine mammals and sea turtles for a certain amount of time before acoustic sound sources can be operated.

All survey vessels must also have an onboard visual observer, someone whose job is to watch out for marine mammals and keep a detailed record of any sightings.

Offshore wind projects are gearing up

In March 2023, the Department of Energy published a 94-page document outlining plans for deploying 30 gigawatts of wind energy into the U.S. grid by 2030 and 110 gigawatts by 2050. According to the report, the U.S. “has just begun to tap the vast resource potential along its coasts.”

If the administration’s goal of 30 gigawatts by 2030 is achieved, it “would translate to more than 77,300 employed workers in jobs induced by offshore wind activity, capital investments in offshore wind energy projects of more than $12 billion per year, and 5-10 new manufacturing plants” for producing equipment like wind turbine blades, towers, foundations, and sub-sea cables, the report says.

As of September 2023, there were 16 offshore wind farm projects under review, and three have already been approved by the Biden administration. The Block Island Wind Farm, owned by Ørsted, a Danish multinational company, has five wind turbines and is considered to be a pilot project in U.S. offshore wind.

Undoubtedly, the huge effort to build these projects will have some impacts on marine life, but whales washing up dead on the shore because of sonar just isn’t one of them, according to the experts.

“If you care about whales, there are a lot of other things to be worried about,” said Andrew Read, the Duke University marine biologist. Though he thinks that the misinformation campaign is unfortunate, he sees one silver lining. “There is a lot of attention on whales, which is great.”

Yale Climate Connections

Yale Climate Connections is a nonpartisan, multimedia service providing daily broadcast radio programming and original web-based reporting, commentary, and analysis on the issue of climate change, one of the greatest challenges and stories confronting modern society.

Since the fall of 2007, Yale Climate Connections has aimed to help citizens and institutions understand how the changing climate is already affecting our lives. It seeks to help individuals, corporations, media, non-governmental organizations, government agencies, academics, artists, and more learn from each other about constructive “solutions” so many are undertaking to reduce climate-related risks and wasteful energy practices.