Republished with permission from The Conversation, by Michael Blake, University of Washington

On Nov. 16, 2023, the bipartisan House Committee on Ethics issued a scathing report on the behavior of Rep. George Santos, finding that Santos had engaged in “knowing and willful violations of the Ethics in Government Act.” That committee’s Republican chair later introduced a motion to expel Santos from Congress. Regardless of the success or failure of that motion, which will be considered after Thanksgiving, Santos himself has announced he will not seek reelection.

These consequences are being brought to bear on Santos in large part because of what the report calls a “constant stream of lies to his constituents, donors, and staff.” Santos appears to have deceived donors about what their money would be used for. Ostensible campaign donations were redirected for his private use, including purchases of Botox and subscriptions to OnlyFans, an X-rated entertainment service.

What, though, makes Santos’ lies so unusual—and so damning? The idea that politicians are dishonest is, at this point, something of a cliché—although few have taken their dishonesty as far as Santos, who seems to have lied about his education, work history, charitable activity, athletic prowess and even his place of residence.

Santos may be exceptional in how many lies he has told, but politicians seeking election have incentives to tell voters what they want to hear—and there is some empirical evidence that a willingness to lie may be helpful in the process of getting elected. Voters may not appreciate candidates who are unwilling or unable to mislead others from time to time.

As a political philosopher whose work focuses on the moral foundations of democratic politics, I am interested in the moral reasons behind voters’ right to feel resentment when they discover that their elected representatives have lied to them.

Political philosophers offer four distinct responses to this question—although none of these responses suggests that all lies are necessarily morally wrong.

1. Lying Is Manipulative

The first reason to resent being lied to is that it is a form of disrespect. When you lie to me, you treat me as a thing to be manipulated and used for your purposes. In the terms used by philosopher Immanuel Kant, when you lie to me, you treat me as a means or a tool, rather than a person with a moral status equal to your own.

Kant himself took this principle as a reason to condemn all lies, however useful—but other philosophers have thought that some lies were so important that they might be compatible with, or even express, respect for citizens.

Plato, notably, argues in “The Republic” that when the public good requires a leader to lie, the citizens should be grateful for the deceptions of their leaders.

Michael Walzer, a modern political philosopher, echoes this idea. Politics requires the building of coalitions and the making of deals—which, in a world full of moral compromise, may entail being deceptive about what one is planning and why. As Walzer puts it, no one succeeds in politics without being willing to dirty their hands—and voters should prefer politicians to get their hands dirty if that is the cost of effective political agency.

2. Abuse of Trust

A second reason to resent lies begins with the idea of predictability. If our candidates lie to us, we cannot know what they really plan to do—and, hence, cannot trust that we are voting for the candidate who will best represent our interests.

Modern political philosopher Eric Beerbohm argues that when politicians speak to us, they invite us to trust them—and a politician who lies to us abuses that trust in a way that we may rightly resent.

These ideas are powerful, but they also seem to have some limits. Voters may not need to believe candidates’ words in order to understand their intentions and thereby come to accurate beliefs about what they plan to do.

To take one recent example: The majority of those who voted for Donald Trump in 2016, when he was trumpeting the idea of making Mexico pay for a border wall, did not believe that it was actually possible to build a wall that would be paid for by Mexico. They did not take Trump to be describing a literal truth, but expressing an untruth that was indicative of Trump’s overall attitude toward migration and toward Mexico—and voted for him on the basis of that attitude.

3. Electoral Mandate

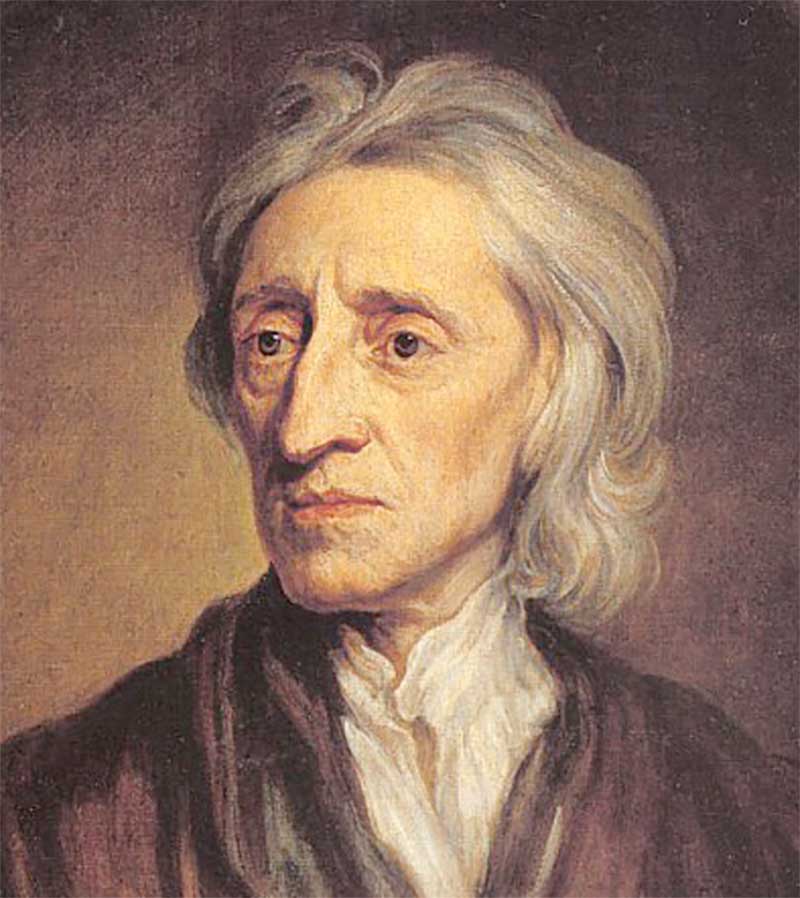

The third reason we might resent lies told on the campaign trail stems from the idea of an electoral mandate. Philosopher John Locke, whose writings influenced the Declaration of Independence, regarded political authority as stemming from the consent of the governed; this consent might be illegitimate were it to be obtained by means of deception.

Philosopher John Locke championed the idea of the consent of the governed. Bettmann via Getty Images

This idea, too, has power—but it also runs up against the sophistication of both modern elections and modern voters. After all, campaigns do not pretend to give a dispassionate description of political ideals. They are closer to rhetorical forms of combat and involve considerable amounts of deliberate ambiguity, rhetorical presentation and self-interested spin.

More to the point, though, voters understand this context and rarely regard any candidate’s presentation as stemming solely from a concern for the unalloyed truth.

4. Unnecessary and Disprovable

Santos’ lies, however, do seem to have provoked something like resentment and outrage, which suggests that they are somehow unlike the usual forms of deceptive practice undertaken during political campaigns.

Certainly the congressional response to these lies is extraordinary. If Santos is expelled from Congress, he would be only the third member of that body to have been expelled since the Civil War.

The rarity of this sanction may reflect a final reason to resent deception, which is that voters especially dislike being lied to unnecessarily—nor about matters subject to easy empirical proof or disproof. It seems clear that voters may sometimes be willing to accept deceptive and dissembling political candidates, given the fact that effective statecraft may involve the use of deceptive means. Santos, however, lied about matters as tangential to politics as his nonexistent history as a star player for Baruch College’s volleyball team.

This lie was unnecessary, given its tenuous relationship to his candidacy for the House of Representatives, and easily disproved, given the fact that he did not actually attend Baruch. Similarly, the ethics report on Santos emphasized the fact that his expenditures often involved purchases for which there was no plausible relationship to a campaign, including US$6,000 at luxury goods store Ferragamo. The proposition that such a purchase was useful for his election campaign is difficult to defend—or to believe.

I believe voters may have made their peace with some deceptive campaign practices. If Walzer is right, they should expect that an effective candidate will be imperfectly honest, at best. But candidates who are both liars and bad at lying can find no such justification, since they are unlikely to be believed and thus incapable of achieving those goods that justify their deception.

If voters have made their peace with some degree of lying, in short, they are nonetheless still capable of resenting candidates who are unskilled at the craft of political deception.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on Jan. 20, 2023.![]()

Michael Blake, Professor of Philosophy, Public Policy and Governance, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation

The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good. We publish trustworthy and informative articles written by academic experts for the general public and edited by our team of journalists.