Republished with permission from Steve Schmidt

There is only one type of society that has ever existed where the Jews have been safe. Democratic societies are those places. When they grow weak, decayed and distressed, Jews become endangered. This has always been so, from antiquity through this American morning.

There is an explosion of antisemitism across the world, and suddenly millions of Jews who couldn’t understand the meaning of their grandparents’ stories suddenly understand them. This understanding was central to the great perspective that Avner Less gained sitting across from Adolf Eichmann in an interrogation room.

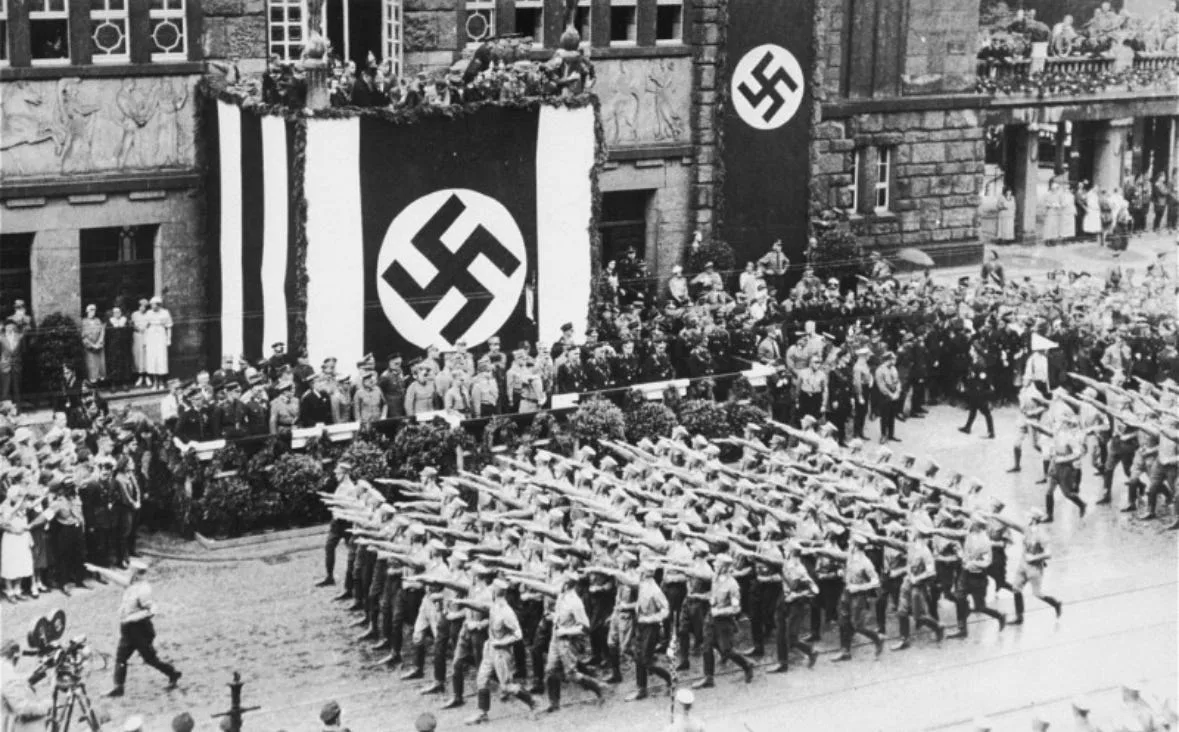

We are upon an anniversary that must be noted within the context of exploding antisemitism and rising hate, particularly across America’s elite universities where a dogma of Jew hate is confused with progressive values and profound empathy for the Palestinian people who live as Hamas’s hostages. All the while, Hamas slaughters the babies of Israeli parents in atrocities that harken names such as Babi Yar, Sobibor, Auschwitz, Chelmno, Dachau and Lidice. The cheering of terrorists and butchers in the name of Palestinian statehood is as great an evil as the masses that cried in ecstasy as torches and swastikas marched by at party rallies in Nuremberg.

Let us understand this moment with perfect clarity. The words “Never Again” and “Never Forget” have been nullified for many within three years’ time of Trump’s violent rejection of the peaceful transition of power, and the results of a presidential election as the cornerstone of the American civilization and a beacon to the world’s oppressed and marginalized. “Things fall apart. The center will not hold.”

When Adolf Hitler came to power, his new hatred was well known and utterly incendiary. SA paramilitary mobs beat Jews in the street and menaced political rivals like the Proud Boys or Patriot Front have done in Trump’s name in modern America. However, they lacked the power to make government policy until 1933 when the Nazi Führer became the German Chancellor and then Führer, absolute leader of the Thousand-Year Reich.

SA parade

An Indianapolis chapter of Proud Boys (Robert Scheer/IndyStar)

The white supremacist group Patriot Front demonstrate near the National Archives in Washington, Friday, January 21, 2022 (Jose Luis Magana/AP Photo)

The laws and edicts came quickly in 1933. Hitler declared a boycott of Jewish-owned businesses across Germany in April of 1933. Jews working for the German government were forced to retire. Jews were forbidden to engage in professional services like the practice of law and teaching. Markets were closed to Jewish products, and all Jews who were naturalized citizens were stripped of their German citizenship. Jewish books were being burned in bonfires by May of 1933, while Jews lost the right to advertise in newspapers and receive government contracts.

In the following year—1934—the situation became much worse. The violence increased, and Jewish life shrank to the quiet corners of German life—cast out, afraid.

Nineteen thirty-five saw the passage of the Nuremberg Race Laws. Let it be known forever that among America’s greatest shames is the undisputed fact that the Nazis based these laws on the most odious miscegenation laws of the deep American South.

The Nuremberg Race Laws stripped citizenship from Jews, and took away every legal right and status with the stroke of a pen. The laws were passed.

Article 1

- Marriages between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if concluded abroad to circumvent this law.

- Annulment proceedings can be initiated only by the state prosecutor.[50]

Article 2

Extramarital relations between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden.[50]

Article 3

Jews may not employ in their households female citizens of German or related blood who are under 45 years old.[50]

Article 4

- Jews are forbidden to fly the Reich or national flag or display Reich colours.

- They are, on the other hand, permitted to display the Jewish colours. The exercise of this right is protected by the state.[50]

Article 5

- Any person who violates the prohibition under Article 1 will be punished with prison with hard labour [Zuchthaus].

- A male who violates the prohibition under Article 2 will be punished with prison [Gefängnis] or prison with hard labour.

- Any person violating the provisions under Articles 3 or 4 will be punished with prison with hard labour for up to one year and a fine, or with one or the other of these penalties.[50]

Article 6

The Reich Minister of the Interior, in co-ordination with the Deputy of the Führer and the Reich Minister of Justice, will issue the legal and administrative regulations required to implement and complete this law.[50]

Article 7

The law takes effect on the day following promulgation, except for Article 3, which goes into force on 1 January 1936.[50]

Reich Citizenship Law

The Reichstag has unanimously enacted the following law, which is promulgated herewith:

Article 1

- A subject of the state is a person who enjoys the protection of the German Reich and who in consequence has specific obligations toward it.

- The status of subject of the state is acquired in accordance with the provisions of the Reich and the Reich Citizenship Law.[50]

Article 2

- A Reich citizen is a subject of the state who is of German or related blood, and proves by his conduct that he is willing and fit to faithfully serve the German people and Reich.

- Reich citizenship is acquired through the granting of a Reich citizenship certificate.

- The Reich citizen is the sole bearer of full political rights in accordance with the law.[50]

Article 3

The Reich Minister of the Interior, in co-ordination with the Deputy of the Führer, will issue the legal and administrative orders required to implement and complete this law.

The antisemitism in Nazi Germany abated in 1936 because the world came to Berlin for the Olympics. The Nazis put on a great show for the world. How bad could the Jews really have it after all? Most of the world was transfixed by the shininess of the Nazi regime with all of its uniforms and handsome young Aryans wearing them. Americans, particularly American businesses and Hollywood studios, were deeply enamored by the German “miracle” and the efficiency of the fascist powers. The record will always show that the first American movie to criticize the Nazis was released by Warner Brothers in 1939. It was called “Confessions of a Nazi Spy.”

When the Olympics ended, the Nazis prepared for war and the screws began tightening on the Jews again. They tightened and tightened until Ernst vom Rath, a Nazi official in Paris, was assassinated by Herschel Grynszpan, a 17-year-old Polish Jew, on November 7, 1938.

What followed was a state-incited pogrom that followed the words and commands of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels.

Joseph Goebbels

What followed was Kristallnacht. It means the “night of broken glass.” Thirty thousand Jews were deported to concentration camps. A $1 billion dollar Reich tax was passed on all Jews. It was collective punishment. Every Jew lost everything—their money, assets, businesses, property and dignity. Jewish children were shut out of schools. It had taken five years, but the German Jews who had lived as Germans, and fought and died as German soldiers a generation before, were completely excised from the society—dehumanized, humiliated, threatened, bullied and impoverished. They were stripped of citizenship, property, passports and any rights whatsoever.

Four more years would pass before the systematic murder of every Jew was planned at Wansee in January 1942 at the apogee of the Nazi Reich. Millions would be gassed, shot and turned to ash before Hitler was dead on April 30, 1945.

Here is the speech delivered by Elie Wiesel from the White House, at the invitation of President and Mrs. Clinton from the White House in 1999:

Mr. President, Mrs. Clinton, members of Congress, Ambassador Holbrooke, Excellencies, friends:

Fifty-four years ago to the day, a young Jewish boy from a small town in the Carpathian Mountains woke up, not far from Goethe’s beloved Weimar, in a place of eternal infamy called Buchenwald. He was finally free, but there was no joy in his heart. He thought there never would be again. Liberated a day earlier by American soldiers, he remembers their rage at what they saw. And even if he lives to be a very old man, he will always be grateful to them for that rage, and also for their compassion. Though he did not understand their language, their eyes told him what he needed to know—that they, too, would remember, and bear witness.

And now, I stand before you, Mr. President—Commander-in-Chief of the army that freed me, and tens of thousands of others—and I am filled with a profound and abiding gratitude to the American people. “Gratitude” is a word that I cherish. Gratitude is what defines the humanity of the human being. And I am grateful to you, Hillary, or Mrs. Clinton, for what you said, and for what you are doing for children in the world, for the homeless, for the victims of injustice, the victims of destiny and society. And I thank all of you for being here.

We are on the threshold of a new century, a new millennium. What will the legacy of this vanishing century be? How will it be remembered in the new millennium? Surely it will be judged, and judged severely, in both moral and metaphysical terms. These failures have cast a dark shadow over humanity: two World Wars, countless civil wars, the senseless chain of assassinations (Gandhi, the Kennedys, Martin Luther King, Sadat, Rabin), bloodbaths in Cambodia and Algeria, India and Pakistan, Ireland and Rwanda, Eritrea and Ethiopia, Sarajevo and Kosovo; the inhumanity in the gulag and the tragedy of Hiroshima. And, on a different level, of course, Auschwitz and Treblinka. So much violence; so much indifference.

What is indifference? Etymologically, the word means “no difference.” A strange and unnatural state in which the lines blur between light and darkness, dusk and dawn, crime and punishment, cruelty and compassion, good and evil. What are its courses and inescapable consequences? Is it a philosophy? Is there a philosophy of indifference conceivable? Can one possibly view indifference as a virtue? Is it necessary at times to practice it simply to keep one’s sanity, live normally, enjoy a fine meal and a glass of wine, as the world around us experiences harrowing upheavals?

Of course, indifference can be tempting—more than that, seductive. It is so much easier to look away from victims. It is so much easier to avoid such rude interruptions to our work, our dreams, our hopes. It is, after all, awkward, troublesome, to be involved in another person’s pain and despair. Yet, for the person who is indifferent, his or her neighbor are of no consequence. And, therefore, their lives are meaningless. Their hidden or even visible anguish is of no interest. Indifference reduces the Other to an abstraction.

Over there, behind the black gates of Auschwitz, the most tragic of all prisoners were the “Muselmanner,” as they were called. Wrapped in their torn blankets, they would sit or lie on the ground, staring vacantly into space, unaware of who or where they were—strangers to their surroundings. They no longer felt pain, hunger, thirst. They feared nothing. They felt nothing. They were dead and did not know it.

Rooted in our tradition, some of us felt that to be abandoned by humanity then was not the ultimate. We felt that to be abandoned by God was worse than to be punished by Him. Better an unjust God than an indifferent one. For us to be ignored by God was a harsher punishment than to be a victim of His anger. Man can live far from God—not outside God. God is wherever we are. Even in suffering? Even in suffering.

In a way, to be indifferent to that suffering is what makes the human being inhuman. Indifference, after all, is more dangerous than anger and hatred. Anger can at times be creative. One writes a great poem, a great symphony. One does something special for the sake of humanity because one is angry at the injustice that one witnesses. But indifference is never creative. Even hatred at times may elicit a response. You fight it. You denounce it. You disarm it.

Indifference elicits no response. Indifference is not a response. Indifference is not a beginning; it is an end. And, therefore, indifference is always the friend of the enemy, for it benefits the aggressor—never his victim, whose pain is magnified when he or she feels forgotten. The political prisoner in his cell, the hungry children, the homeless refugees—not to respond to their plight, not to relieve their solitude by offering them a spark of hope is to exile them from human memory. And in denying their humanity, we betray our own.

Indifference, then, is not only a sin, it is a punishment.

And this is one of the most important lessons of this outgoing century’s wide-ranging experiments in good and evil.

In the place that I come from, society was composed of three simple categories: the killers, the victims, and the bystanders. During the darkest of times, inside the ghettoes and death camps—and I’m glad that Mrs. Clinton mentioned that we are now commemorating that event, that period, that we are now in the Days of Remembrance—but then, we felt abandoned, forgotten. All of us did.

And our only miserable consolation was that we believed that Auschwitz and Treblinka were closely guarded secrets; that the leaders of the free world did not know what was going on behind those black gates and barbed wire; that they had no knowledge of the war against the Jews that Hitler’s armies and their accomplices waged as part of the war against the Allies. If they knew, we thought, surely those leaders would have moved heaven and earth to intervene. They would have spoken out with great outrage and conviction. They would have bombed the railways leading to Birkenau, just the railways, just once.

And now we knew, we learned, we discovered that the Pentagon knew, the State Department knew. And the illustrious occupant of the White House then, who was a great leader—and I say it with some anguish and pain, because, today is exactly 54 years marking his death—Franklin Delano Roosevelt died on April the 12th, 1945. So he is very much present to me and to us. No doubt, he was a great leader. He mobilized the American people and the world, going into battle, bringing hundreds and thousands of valiant and brave soldiers in America to fight fascism, to fight dictatorship, to fight Hitler. And so many of the young people fell in battle. And, nevertheless, his image in Jewish history—I must say it—his image in Jewish history is flawed.

The depressing tale of the St. Louis is a case in point. Sixty years ago, its human cargo—nearly 1,000 Jews—was turned back to Nazi Germany. And that happened after the Kristallnacht, after the first state sponsored pogrom, with hundreds of Jewish shops destroyed, synagogues burned, thousands of people put in concentration camps. And that ship, which was already in the shores of the United States, was sent back. I don’t understand. Roosevelt was a good man, with a heart. He understood those who needed help.

Why didn’t he allow these refugees to disembark? A thousand people—in America, the great country, the greatest democracy, the most generous of all new nations in modern history. What happened? I don’t understand. Why the indifference, on the highest level, to the suffering of the victims?

But then, there were human beings who were sensitive to our tragedy. Those non-Jews, those Christians, that we call the “Righteous Gentiles,”whose selfless acts of heroism saved the honor of their faith. Why were they so few? Why was there a greater effort to save SS murderers after the war than to save their victims during the war? Why did some of America’s largest corporations continue to do business with Hitler’s Germany until 1942? It has been suggested, and it was documented, that the Wehrmacht could not have conducted its invasion of France without oil obtained from American sources. How is one to explain their indifference?

And yet, my friends, good things have also happened in this traumatic century: the defeat of Nazism, the collapse of communism, the rebirth of Israel on its ancestral soil, the demise of apartheid, Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt, the peace accord in Ireland. And let us remember the meeting, filled with drama and emotion, between Rabin and Arafat that you, Mr. President, convened in this very place. I was here and I will never forget it.

And then, of course, the joint decision of the United States and NATO to intervene in Kosovo and save those victims, those refugees, those who were uprooted by a man, whom I believe that because of his crimes, should be charged with crimes against humanity.

But this time, the world was not silent. This time, we do respond. This time, we intervene.

Does it mean that we have learned from the past? Does it mean that society has changed? Has the human being become less indifferent and more human? Have we really learned from our experiences? Are we less insensitive to the plight of victims of ethnic cleansing and other forms of injustices in places near and far? Is today’s justified intervention in Kosovo, led by you, Mr. President, a lasting warning that never again will the deportation, the terrorization of children and their parents, be allowed anywhere in the world? Will it discourage other dictators in other lands to do the same?

What about the children? Oh, we see them on television, we read about them in the papers, and we do so with a broken heart. Their fate is always the most tragic, inevitably. When adults wage war, children perish. We see their faces, their eyes. Do we hear their pleas? Do we feel their pain, their agony? Every minute one of them dies of disease, violence, famine.

Some of them—so many of them—could be saved.

And so, once again, I think of the young Jewish boy from the Carpathian Mountains. He has accompanied the old man I have become throughout these years of quest and struggle. And together we walk towards the new millennium, carried by profound fear and extraordinary hope.

It was the honor of my lifetime to accompany Elie Wiesel to Auschwitz as part of the American delegation to commemorate the 60th anniversary of its liberation in 2005. Nearly 20 years have passed since then, and the world has turned many times. It has become dangerous for Jews again. It has become dangerous, not because the enemies of tolerance, liberty and freedom are strong, but rather because the democracies who defend these values are weak.

Fascism did not thrive in the 1930s because it was strong. It thrived because the democracies were weak. We must understand that in this moment of grave danger.

Steve Schmidt

Steve Schmidt is a political analyst for MSNBC and NBC News. He served as a political strategist for George W. Bush and the John McCain presidential campaign. Schmidt is a founder of The Lincoln Project, a group founded to campaign against former President Trump. It became the most financially successful Super-PAC in American history, raising almost $100 million to campaign against Trump's failed 2020 re-election bid. He left the group in 2021.