Republished from Governing.com, by Carl Smith

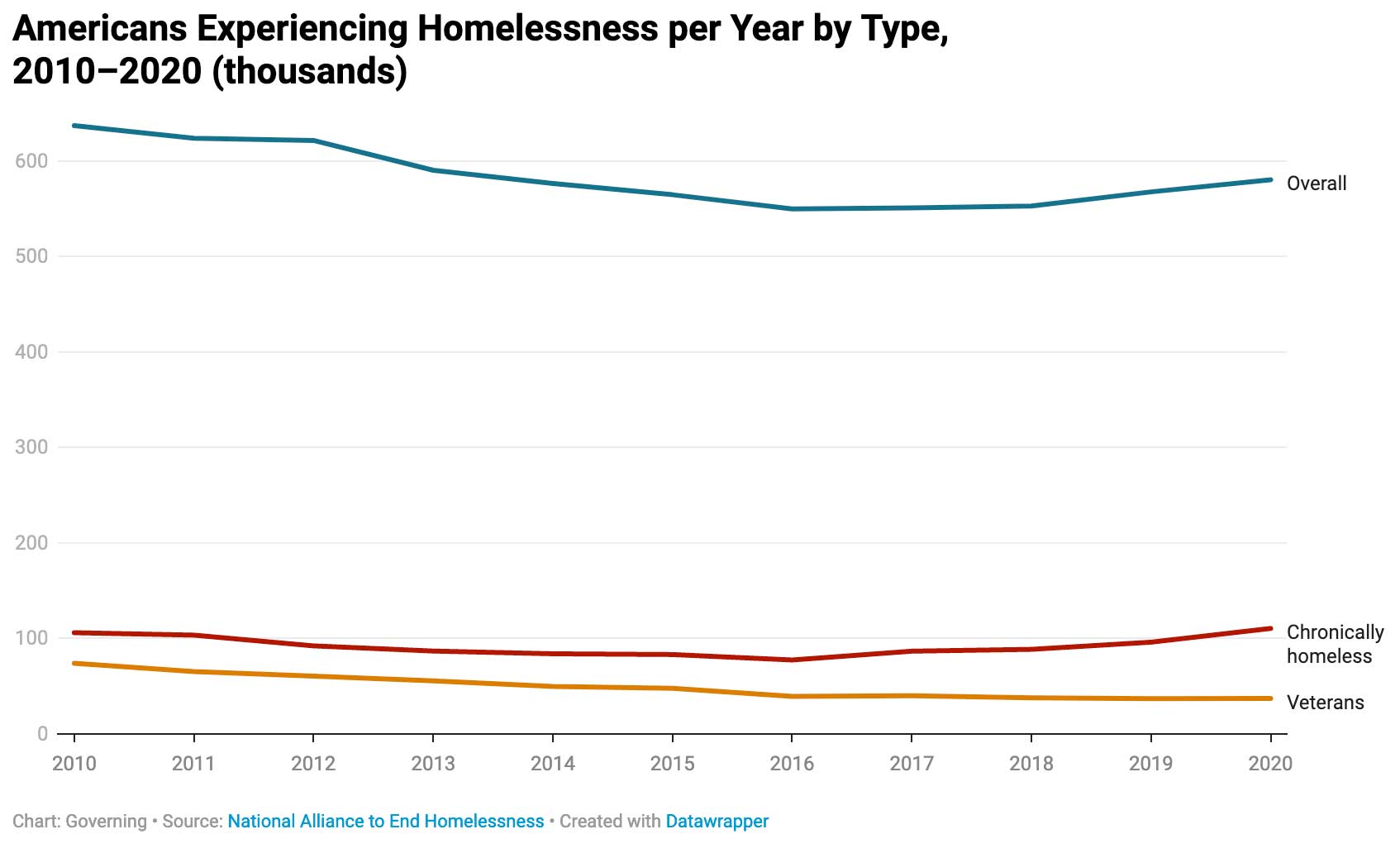

Nearly 600,000 Americans were homeless in January 2020. The majority (70 percent) were individuals, the rest families with children. This was the size of the unhoused population before the pandemic upended tenuous social and economic supports that keep roofs over the heads of at-risk populations.

Four out of five homeless service providers who responded to an April survey by the National Alliance to End Homelessness reported that requests for help were increasing. Two-thirds suspected that the population of unsheltered homeless was growing.

There’s not yet a clear national picture of how well eviction moratoriums and billions in unemployment benefits and rent relief may have kept things in check. Whatever the case may be, COVID-19 has underscored why the right to housing is included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Amanda Harris, chief of services to end and prevent homelessness for the Montgomery County, Md., Department of Health and Human Services, has seen public perceptions change during the pandemic, as renters fall behind and evictions loom. “Folks realize how close so many people are to the edge, that homelessness is not something that happens to others,” she says. “It can happen to anyone.”

Montgomery County is one of scores of jurisdictions across the country that are part of a movement to end homelessness by focusing on building pathways to housing with assistance from a New York-based nonprofit.

The Right Number Is Zero

Rosanne Haggerty, president and CEO of Community Solutions, had her first encounter with the homeless when she volunteered at a shelter just after graduating from college. Homelessness was a newly named issue at the time, and the clients in the shelter were her age.

“I realized that the very well-intentioned folks staffing the shelter had very crazy assumptions about what was going on,” she says. The AIDS and crack epidemics were spreading, and 30 days of crisis shelter fell far short of meeting the needs of youth who had fled to the streets from broken families or group homes.

“I saw that we were asking the wrong questions,” she says. “If we put our attention on unpeeling what the real solutions needed to look like and facing to that, we could be getting somewhere.”

To act on this perception, she founded in 1990 a nonprofit housing development and management organization in New York City, Common Ground Community. Her efforts included projects that salvaged historic buildings, resulting in nearly 3,000 affordable homes. In recognition of her innovative approach to this work, she was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2001.

In 2011, she founded a new nonprofit, Community Solutions. Its first campaign set a goal of housing 100,000 of the most chronically homeless and vulnerable Americans. It exceeded this target by 2014, housing 105,580.

“We succeeded in what we specifically aimed to do, but it didn’t actually get any community to an end state on homelessness,” says Haggerty. “We locked onto the idea that we needed to start at the end state of zero homelessness and look at where else in the world people were solving problems at a population level all the way through, not just for the lucky few who got themselves into a good program.”

Rosanne Haggerty on homelessness: “I have always felt optimistic and determined — and confident — that focusing on the right problem and not running from the complexity of it will get us somewhere.” (Community Solutions)

Global health campaigns, in particular the eradication of smallpox, met this standard. These require thinking in systems, building teams around shared aims, and having the right information at the right time to enable groups to problem solve in response to shifting situations.

Community Solutions refined its methodology based on its study of the ways these campaigns created such capacities and what it had learned from its own experience. In 2015, it launched a new initiative, Built for Zero, with the goal of bringing homelessness to a state of “functional zero.”

Functional zero is achieved for the homeless veterans when their number in a community is smaller than the number that can be routinely housed. A community is considered to have ended chronic homelessness if the number of people experiencing this is zero — or if not zero, no more than 3 or 0.1 percent of its most recent count of this population.

Built for Zero work gained considerable momentum in 2020 when Community Solutions was named the winner of the MacArthur Foundation’s global 100&Change competition, which offered a $100 million grant to a single proposal that showed the best potential to achieve real and measurable progress toward a critical problem.

“It was a wonderful validation of the fact that this is a solvable problem,” says Haggerty. “The money will help us accelerate our work and help these amazing communities that are part of the movement to have some of the flexible resources they need to lead.”

The Built for Zero initiative aims to achieve a “functional zero” level of homelessness.

Everyone’s Job Is No One’s Job

Rather than providing direct services to address these issues, Built for Zero coaches, trains and supports local agencies and community groups. It’s presently working with close to 100 communities and is working to expand this by 25 percent.

“We tend to see everybody starting with the same assumption, which is that they don’t have enough housing or resources to make a meaningful dent in the problem,” says Jake Maguire, co-director of Built for Zero. “When we start to dig in, in each of these communities we tend to find other, more urgent problems underneath the surface.”

A fundamental dilemma is that even though there may be many organizations in a community with programs to help the homeless, there’s usually not a clear authority in charge, taking accountability for the problem. Individual groups are accountable to their funders and boards, but don’t have a formal incentive to work together.

“That’s something that surprises people in the general public, that it’s not someone’s job in your community to end homelessness,” he says. “It’s actually lots of people’s jobs, which means that it’s no one’s job.”

Because of this, the multiple entry points through which the unhoused access services don’t have well-understood relationships to one another or see themselves as part of a defined process. The other basic stumbling block, says Maguire, is the lack of a feedback loop. “It’s very hard to know if any of the things you’re trying to do among that collective group of stakeholders is actually adding up to any kind of result.”

Early in its process, Built for Zero works with service providers to help them agree on a shared aim for their work, and to create a “command center,” a group that meets regularly to monitor progress against defined metrics.

Improving the data stream begins an inventory of the local homeless population. “You need to have someone’s name, you need to know enough about their situation to understand what kinds of interventions they might be eligible for, what would make sense for them,” says Maguire. This data needs to be updated regularly, monthly at a minimum, if the command center hopes to stay on top of things.

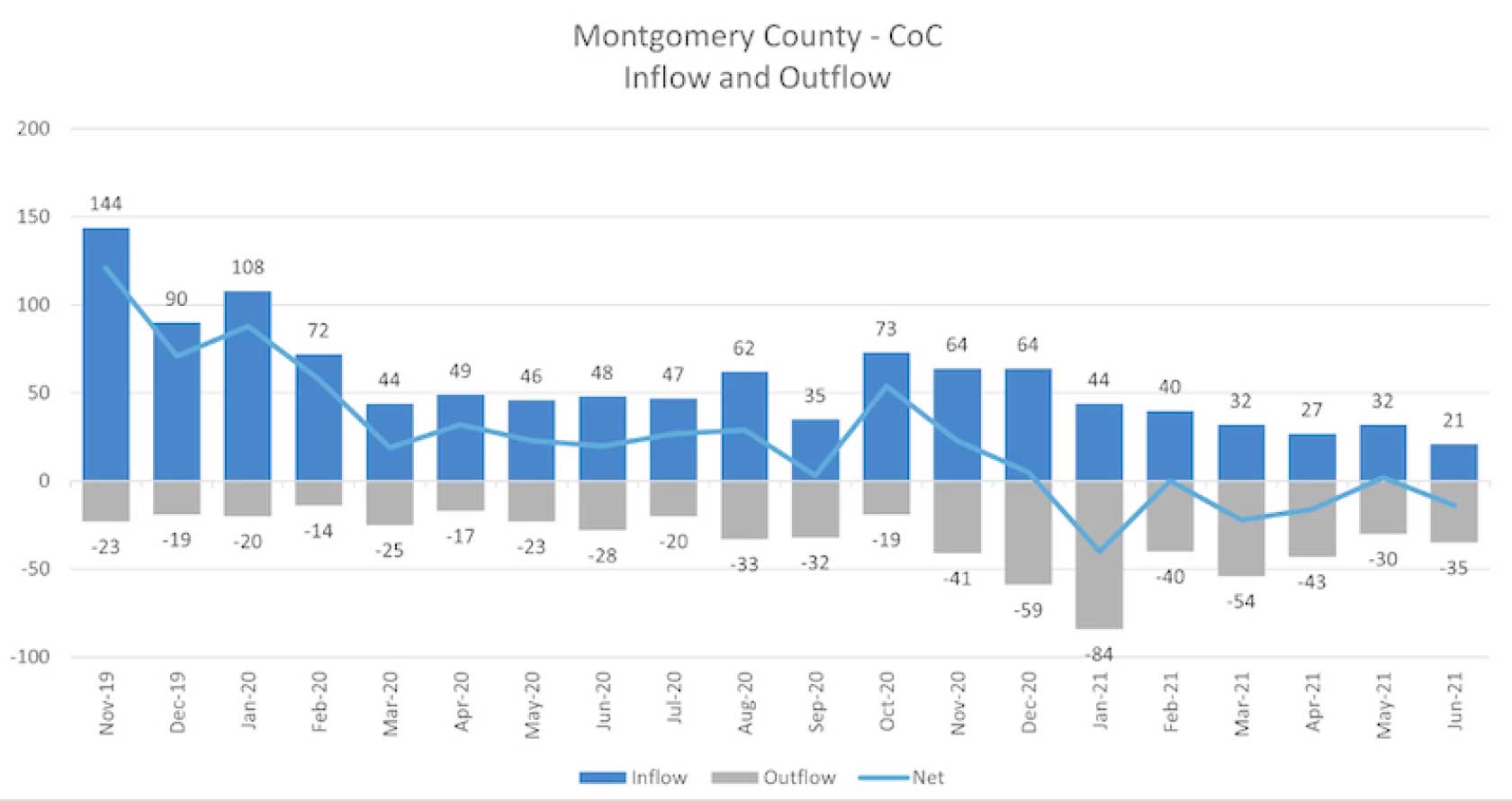

Funding and software development support from the Tableau Foundation led to the creation of a platform for local dashboards tracking data points such as inflow into and out of homelessness, the size of the active homeless population and progress toward the goal of functional zero. These are provided to communities at no cost.

Maguire compares the impact of this data stream to going from a snapshot of homelessness to something that looks more like a movie. This real-time, dynamic window on the situation makes it possible for command center participants to discover better ways to work together.

To date, 14 members of Built for Zero’s collaborative network have achieved functional zero with at least one homeless population. More than 40 have achieved measurable results, and 60 now have high-quality, real-time data about the homeless in their communities.

“There’s no scale of community where this can’t be executed,” says Maguire. It’s not a matter of just dollars and housing units, but creating an operating system, a way of working that maximizes the utility of resources to the greatest effect.

A graph showing the flow of homeless into and out of the Community of Care (CoC) in Montgomery County, MD. (Montgomery County)

Robust and Adaptable

Montgomery County, Md., has not yet reached functional zero for chronic homelessness, says Amanda Harris, but it has reduced it by 90 percent through its Inside/Not Outside initiative. It has set a target of ending homelessness by 2023 and the data collected as it progresses toward this goal has revealed unexpected nuances.

“When we set out to end chronic homelessness, our assumption was that the people that met the federal definition of chronic homelessness were the most vulnerable in our community,” she says. “About a third of the way through, we started to notice that the folks that we were seeing in our shelters and on the street were actually very, very vulnerable, with co- or tri-morbidity, but were not necessarily meeting the federal definition.”

The county compared its data about who had been housed through Inside/Not Outside to the homeless population that had risk factors that, in real-world terms, made them highly vulnerable. The overlap between the two was not nearly as great as expected.

“We decided that our permanent housing placements were going to be based on vulnerability instead of the federal government definition,” says Harris. “An important part of using data is you’ve got to be able to shift, to be really adaptable.”

Data points can also shift. In developing a homeless prevention index, the county learned that single-family homes in Census tracts it viewed as less likely to have a homeless problem had been cut up into multifamily units with high turnover rates. Stakeholder feedback corrected this misperception.

The county has developed a robust, coordinated entry system and a common assessment tool. Homeless service providers meet monthly to discuss placement. As this group has become cohesive, it’s begun to look outward.

It’s well understood that homelessness is often the result of failures in other systems such as criminal justice, behavioral health or foster care, says Harris. “We want to make sure that we’re including those feeder systems in our process, so that they know what we’re doing and can help us move that work further upstream — how do we prevent people from entering our system altogether?”

An interagency commission on homelessness was created to address this, with representatives from all stakeholders, including schools, nonprofits, corrections, child welfare, housing development, philanthropy and the public. “We’ve had more success in some areas than in others, but we’re continuing to focus on that,” says Harris.

Specialized outreach teams have been created to give businesses someone to call if they need help with homeless activity in their vicinity. This involves a good bit of education, Harris says. “Just because someone is outside a business asking for money, we can’t force them to go away. But we can have a conversation, engage, try to see what they need.”

It’s both the best and worst time to be in homeless services, she says. The pandemic has added life-and-death stresses, but it has also brought funding. “I’ve never seen so much money available to people experiencing homelessness. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity to make a serious dent in homelessness.”

Federal money has brought welcome options and flexibility, but it won’t last forever. Harris is concerned about what will happen in a year or two, when federal funding has dried up and populations hit hardest by the pandemic are still struggling. The path to sustained funding, she believes, is proving that it’s possible to actually end homelessness.

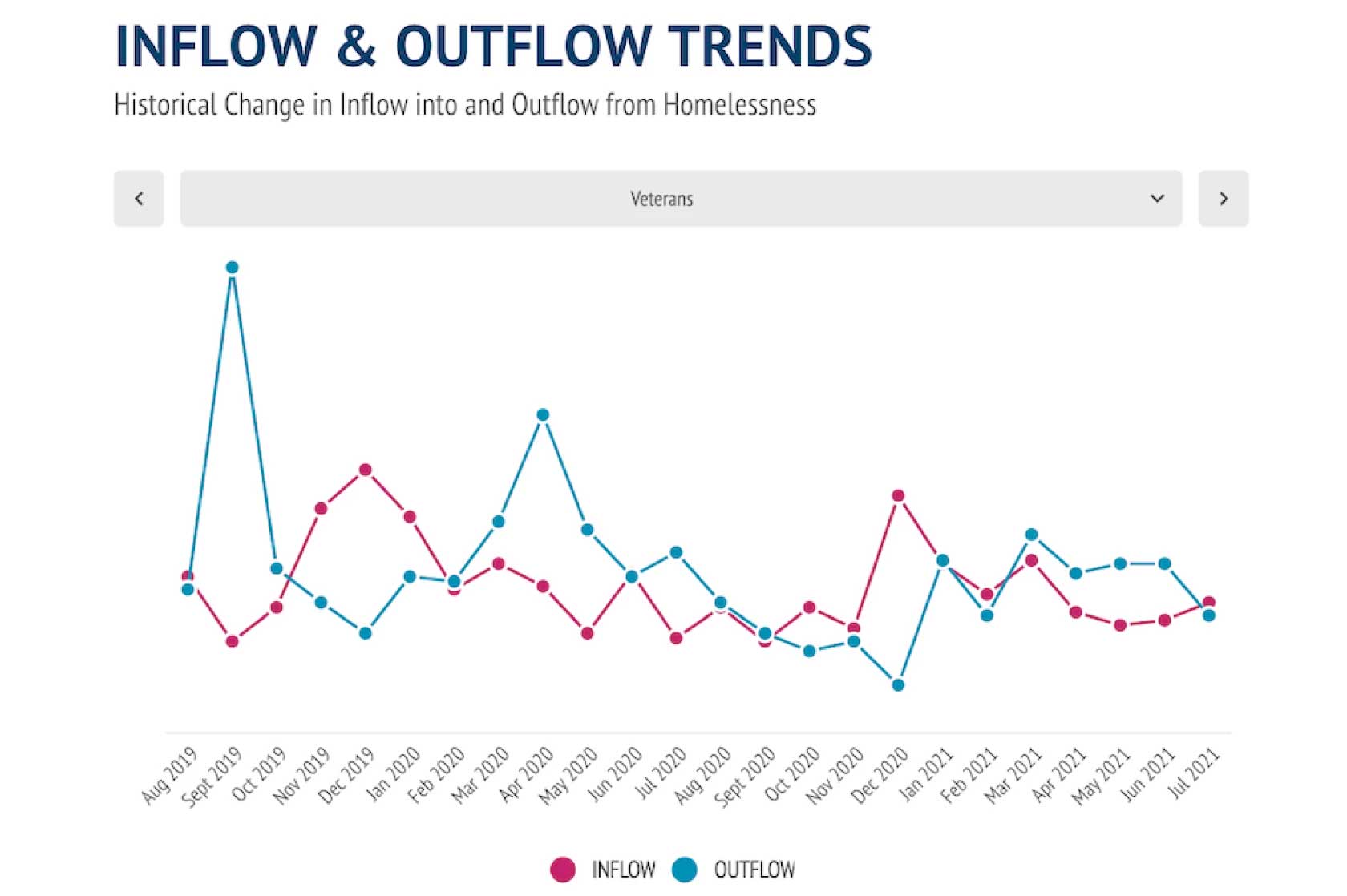

A chart from Meckelenberg County, NC’s, public Housing and Homelessness dashboard shows the rate at which veterans are entering and leaving homelessness. (Mecklenberg County)

Engagement Through Data

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Continuum of Care has been using a homeless management information system for a number of years, says Mary Ann Priester, who coordinates the system for its Community Support Services department (CSS). In 2017 the department launched a public Housing and Homelessness Dashboard that includes a monthly and a real-time count of the number of people in the community who are experiencing homelessness. When it became part of the Built for Zero collaborative, it began to incorporate its metrics as well.

The county partnered with a data coordinator for the dashboard to publish a monthly blog that highlighted the current state of homelessness in the community. “We were really seeking to engage the community around the data and the metrics that are part of the Built for Zero framework,” says Priester.

Mecklenburg County is home to Charlotte, one of the largest cities in the country, and homeless service providers made a practice of case conferencing. Technical assistance from Built for Zero helped these meetings become more structured and participation in a cohort of large cities created opportunities for peer-to-peer learning.

“At first we would meet a lot with smaller cities, and they have different struggles or challenges than a big city would have,” says Karen Pelletier, director of housing strategy, innovation and alignment for CSS. “The fact that we’ve been able to connect more with big cities has helped us think things through differently.”

The county has made significant strides in reducing veteran homelessness. It set a goal of reducing this by 30 percent in 2019, achieved it, then set a target of an additional 30 percent reduction which it is also close to meeting.

Although there aren’t reliable numbers yet, more and larger encampments suggest that the homeless population in Charlotte could be increasing. Pelletier has also seen more residents wanting to do something to help and is working with grassroots organizations to channel this impulse.

“We really need to look at access to service differently,” she says. “With our data we are looking at how we, as a system, can be nimble and create change and reduce barriers, because access to service should not be a barrier in itself.”

This will be a focus as the county continues to move through the pandemic and adjust as needed to whatever comes next. “COVID is never going to go away, and we are going to live with it in our community,” says Pelletier. “We won’t live with it like this, but we’re going to have to learn how to make system improvements while also adjusting to COVID.”

No Silver Bullet

As large as the footprint of homelessness can seem, it represents just one percent of the population of any community. Rosanne Haggerty acknowledges the strangeness of the fact that strategies Built for Zero employs to end it are modeled on those used in a global response to a deadly virus.

“In some ways we seem a little prophetic because we were out there saying, ‘You need to think about this as a public health issue,’” she says. “Public health was not something many people were thinking about until COVID.”

A public health crisis that has exacerbated the homeless crisis is nothing to be thankful for, but it has brought forth urgency and resources at levels that might never have materialized otherwise.

“I feel more optimistic than I ever have in my lifetime’s work on this issue,” says Haggerty.

As is the case with COVID-19, however, she cautions that there is no silver bullet. “There’s a disciplined, population-level solution that many communities are now showing how to achieve.”

Governing

Governing: The Future of States and Localities takes on the question of what state and local government looks like in a world of rapidly advancing technology. Governing is a resource for elected and appointed officials and other public leaders who are looking for smart insights and a forum to better understand and manage through this era of change.