It looks as if the United States is going to begin to come to terms with the dark legacy of the Indian boarding schools. On May 11, 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior released volume one of an investigative report on the history and legacy of these schools, which existed to force Native American children to break with their Native communities and traditions and assimilate into the dominant white culture as quickly as possible and as forcibly as necessary. The 102-page report makes for grim and chilling reading: violence, malnutrition, beatings, sexual abuse, solitary confinement, untreated diseases, unreported deaths and disappearances.

Meanwhile, the U.S. House of Representatives has been considering H.R.5444, the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act. The proposed legislation was introduced on Sept. 30, 2021, by Rep. Sharice Davids of Kansas, one of the first two Native American women elected to Congress. The bill has bipartisan support and 50 co-sponsors. The bill has not yet received a hearing in the U.S. Senate.

According to the Interior Department report, the federal Indian boarding school system (1860-1978) consisted of 408 federal schools in 37 states and territories. About a third of these schools were operated by various Christian denominations. So far, the investigation has identified 53 burial sites associated with these schools, some marked, some unmarked. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, an enrolled member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, has said, “It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.”

Trauma-informed Listening

Secretary Haaland has announced the launch of a yearlong fact-finding tour that will visit Native American communities across America, including both Alaska and Hawaii. “The Road to Healing” will enable Indigenous people to tell their stories and gain access to what is called “trauma-informed support.”

The Indian boarding schools were designed to remove Native American children from their home communities (reservations), and to place them in boarding schools far enough away to ensure that they would not be “corrupted” or held back by their families or their ties to traditional Native culture. This relocation often happened without the consent of the families of these Native children. They were, in effect, kidnapped by white men operating under license from the U.S. government. When they arrived at such schools as Carlisle in Pennsylvania (1879-1918), Haskell in Kansas (1884-1993) or the Chilocco School in Oklahoma (1884-1980) they were forced to surrender their clothing and personal effects to the headmaster and to wear standard school uniforms.

The regimentation was based on U.S. military protocols. The young men’s braids were cut off. They were forced to eat white food and to use white utensils. They were not permitted to speak in their Native languages or practice any of their Native rites or traditions. They were given new white names in an effort to erase not only their heritage but their lineage. Many students never returned home. Beatings for noncompliance were common.

Writing in The Atlantic in 2019, Mary Annette Pember, whose mother attended one of the schools in Wisconsin, called them “institutions created to destroy and vilify Native culture, language, family and spirituality.”

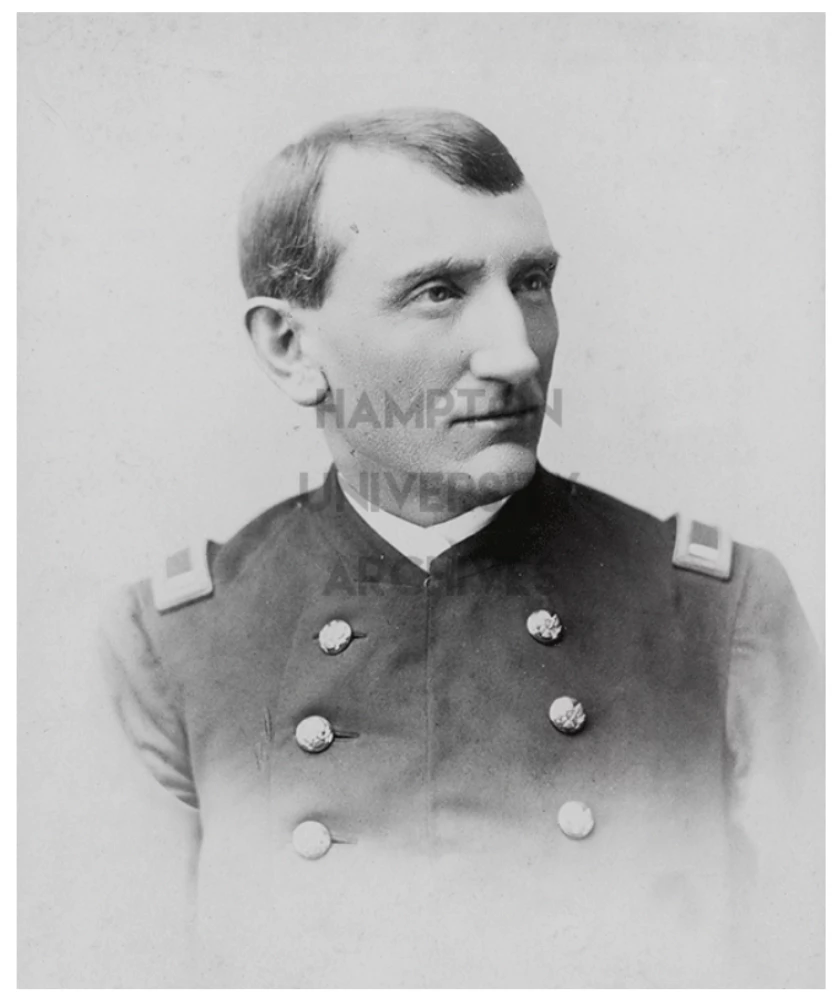

The father of the late 19th-century Indian boarding school movement was a man named Richard Henry Pratt (1840-1924). He created Carlisle Indian School in 1879. Although he thought he was doing the right thing, and though his views were squarely within the white establishment perspective of the era, his language of assimilation was troublingly violent. His motto was, “Kill the Indian, save the Man.” Not reshape the Indian for survival in the dominant culture, but “Kill the Indian.” Pratt also wrote, “In Indian civilization I am [regarded as a] Baptist, because I believe in immersing the Indian in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.” This “play” on the word Baptist and his view that the Native child must be held under the water of civilization until she or he was reborn feels uncomfortably close to waterboarding.

Beware Philanthropists With Good Intentions — “Friends of the Indian”

Any study of the history of American Indian policy reveals that as much damage has been done by the individuals who believed they were philanthropists as by the conquerors (Custer, Sherman, Miles, Crook). It was with this sort of benevolence in mind that in Walden, Henry David Thoreau wrote, “If I knew for a certainty that a man was coming to my house with the conscious design of doing me good, I should run for my life.”

It’s easy to assemble lists of the purposeful acts of conquest and cultural genocide in American history—the Trail of Tears, the Sand Creek Massacre, Wounded Knee, the flight of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce (Nimiipuu), the assassinations of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, the systematic violation (by the U.S. government) of hundreds of treaties solemnly consummated with Native American leaders, the countless “takings” of Native American land by executive orders, unilateral legislative action, the use of alcohol to destabilize individuals and tribal communities, the strategic extermination of the buffalo (very nearly successful) to collapse Native American economies and bring Native Americans to the ration table. The literature of the Europeanization of North America is rich, fascinating and disturbing. For starters, I recommend Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’ An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States (2015) or Dee Brown’s 1970 classic, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

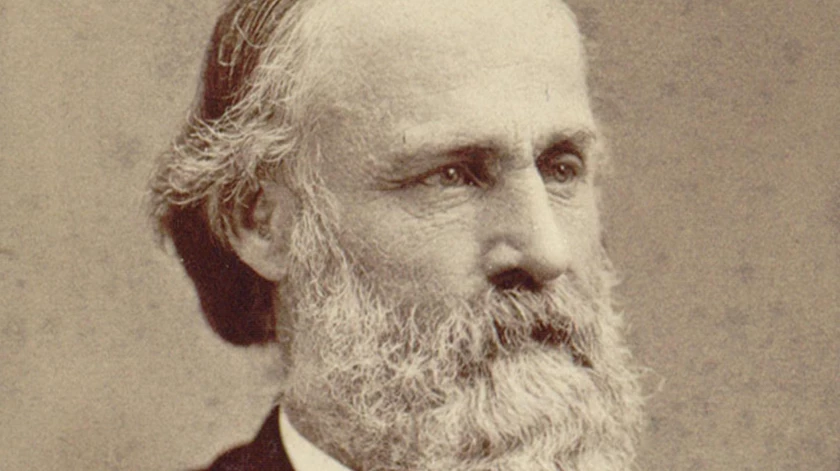

What’s harder to come to terms with is the amount of damage done to Native Americans by earnest white people — filled with respect and good will — who thought they were helping. The white men and women who were somewhat derisively called “Friends of the Indian” did their best to solve what was then called “the Indian problem,” with initiatives, programs and institutions that wound up doing more harm than good or that failed to anticipate the “law of unintended consequences.” The Indian boarding schools were one such initiative, but there were many others. Thomas Jefferson thought the best thing for Native Americans would be temporary removal to the West, so that Natives could get out of harm’s way and come to terms with the rising tide of white settlement more gradually. (He also wanted their land.) Like so many others of his time, Massachusetts Sen. Henry A. Dawes thought the best way to assimilate Native Americans into the white world was to encourage them to embrace the idea of private property. He wanted them to take up family homesteads on their reservations just as their white counterparts had taken up small square parcels in the American West after passage of the Homestead Act of 1862.

Massachusetts Senator Henry A. Dawes. On leaving the Senate in 1893, Dawes became chairman of what was then called the Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes, also known as the Dawes Commission, and served for ten years. He negotiated with the tribes for the extinction of the communal title to their land and for the dissolution of the tribal governments. (Nebraska Public Media)

The Dawes Severalty Act of 1887 attempted to do just that, even though Native Americans had very different concepts of private property, economic life and even family. The provision of the Dawes Act that did the most damage was the section that declared that reservation lands not homesteaded by Indian individuals or families within a certain time period would then be declared “surplus lands,” and made available to non-Indian settlement. This provision of the Dawes Act fractured Indian reservations, causing a checkerboard land ownership pattern. On most Indian reservations in the West, non-Natives still own between a quarter and three-fifths of what on the maps appears to be “Indian Country” or reservation land. In other words, though Henry Dawes was trying to do the right thing, he enabled non-Natives to gobble up millions of acres of sovereign Native American land.

More recently, in the 1950s, the U.S. government sought to terminate the reservation system and relocate Native American individuals and families in a number of target cities across the country, including Minneapolis, Seattle and Los Angeles. The policy was designed to “mainline” Native peoples, hasten their full assimilation and obliterate what were regarded as the unhealthy social and economic conditions of the reservation system.

Truth and Reconciliation Commissions

The idea of truth and reconciliation commissions originated in South Africa after its long nightmare of apartheid ended in 1996. After being imprisoned by the South African regime for 27 years, Nelson Mandela became South Africa’s first elected president and its first Black leader in 1994. A billion people worldwide watched his inauguration on May 10, 1994, in Pretoria. Under Mandela’s leadership the majority-Black National Assembly worked to dismantle apartheid and bring about the beginnings of racial reconciliation. Thousands of Black South Africans had the opportunity to testify. Their oppressors were permitted to seek amnesty for their crimes against humanity. Some were granted amnesty, others not.

Truth and reconciliation commissions vary in structure and approach, but they all give oppressed or victimized individuals the opportunity to tell their stories; speak their minds; express their sorrow, anger and outrage; get a load of long-buried pain off their chests. And they get to do this on the record, with video and audio recording, transcriptions, and official publication of testimony. In most instances the survivors (in some cases their descendants) are given the opportunity to confront their oppressors directly or representatives of the government or institutions that damaged their lives. The oppressors agree to sit and listen — just listen — without interrupting the statement of the person bearing witness and without attempting to justify their actions.

There is usually no legal jeopardy for the oppressors. The idea is not to litigate the abuse or seek formal recrimination, but to create conditions for healing. Perhaps the healing is unilateral for the survivor who now has an opportunity, in a carefully modulated public forum, to speak her or his mind fully and freely, often for the first time. Perhaps the healing is for both parties, because when this is done right, in many instances the oppressor realizes — perhaps for the first time — how much suffering she or he caused, and realizes, too, that this is not how she or he wishes to be remembered, that this is not a full measure of who she or he is. Reconciliation sessions sometimes end with the oppressor and the oppressed weeping openly together, sometimes hugging and the oppressor asking forgiveness.

But even when the confrontation does not lead to genuine reconciliation, the victim is officially given a voice. That can make a huge difference.

Lessons From Our Northern Neighbors

Canada has been engaged in this important work since 2007 following the largest class action litigation in Canadian history. The Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission spent six full years traveling to every region of Canada listening to and recording the testimony of more than 6,500 Indigenous witnesses. The government of Canada provided the commission with more than 5 million records from the archives of what are called residential schools. The six-volume final report is widely available and, importantly, not just retrospective. It includes 94 “calls to action,” including recognition and promotion of aboriginal languages; closing the gap in access to health care between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations; seeking ways to reduce the over-representations of Indigenous people in Canadian prisons; and requiring government, institutions and religious denominations to repudiate the Doctrine of Discovery and the concept of “terra nullius,” which enabled white Europeans to claim lands and resources that belonged to aboriginal peoples in Canada.

In March 2022, Pope Francis apologized to the Indigenous Peoples of Canada and begged for forgiveness — in person, at the Vatican — for the “deplorable” abuses they suffered in Catholic-run boarding schools.

Drummers from the Tk’emlups te Secwepemc First Nation commemorate meetings between indigenous delegates and Pope Francis at the Vatican. (Associated Press)

So far, the Canadian commission has found 1,350 graves at the residential schools.

A New Era in the United States

These developments led Secretary Haaland to order a similar investigation of boarding school graves in the United States, and to set in motion the more comprehensive investigation that Haaland hopes the U.S. Congress will embrace and support. Even without formal congressional approval, Haaland is determined to accomplish as much as she can using her existing authority and funds.

Elections matter. If President Biden had not appointed the first Native American secretary of the interior, Deb Haaland, and if Sharice Davids (D-KS) and Yvette Herrell (R-NM) had not been elected to Congress, it seems unlikely that this bold initiative would have been undertaken at this time. It’s hard to imagine the previous administration’s Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke embracing the idea of truth and reconciliation initiatives, even in his own Montana.

There are people who reject the idea of these reconciliation commissions and reports, who believe there is nothing white America or its government needs to apologize for. Even some who believe historic wrongs occurred say that was then and this is now. There are people who wish to say to Native Americans, get over it, or more emphatically, get over it already! These are complicated issues, with room for honest debate in several directions.

We should remember, however, that Native Americans have special status in the U.S. Constitution; that in the most important sister piece of legislation in the year of the founding, 1787, the Northwest Ordinance, the Founders insisted that the U.S. government must always show “the utmost good faith” in its trust relationship with Native Americans; and that America’s greatest Chief Justice John Marshall famously interpreted those documents as defining American Indians as “domestic dependent sovereigns,” in other words, nation states within a larger, overarching nation state called the United States of America.

What is perhaps most impressive about these commissions is how much real good can be done at very little “cost.” To find a formal platform for Native Americans to express their pain and confront their oppressors, and to know that what they have to say is heard with real respect, is to go a long way toward a new era in white-Indian relations. There are difficult practical things that must still be done, including deeding some lands back to their Native sovereigns; retiring some icons, statues, faux-Indian artifacts and sports team nicknames; doing justice to Native mineral and water rights; and much more. But it is breathtaking to see what a simple and sincere apology can do by way of breaking the pattern of occupation and oppression.

That most difficult of Christian obligations — forgiveness — often begins when the wrongdoer expresses a simple and sincere apology.

Republished with permission from Governing Magazine, by Clay S. Jenkinson

Governing

Governing: The Future of States and Localities takes on the question of what state and local government looks like in a world of rapidly advancing technology. Governing is a resource for elected and appointed officials and other public leaders who are looking for smart insights and a forum to better understand and manage through this era of change.