PFAS are showing up in water systems across the U.S. Photo by Jacek Dylag, Unsplash

PFAS are showing up in water systems across the U.S. Photo by Jacek Dylag, Unsplash

New EPA rules will require years for testing and even more years for final removal of PFAS chemicals from water systems. But there are things we can do to protect our homes now.

Republished with permission from The Conversation, by Kyle Doudrick, University of Notre Dame

Chemists invented PFAS in the 1930s to make life easier: Nonstick pans, waterproof clothing, grease-resistant food packaging and stain-resistant carpet were all made possible by PFAS. But in recent years, the growing number of health risks found to be connected to these chemicals has become increasingly alarming.

PFAS—perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances—are now either suspected or known to contribute to thyroid disease, elevated cholesterol, liver damage and cancer, among other health issues.

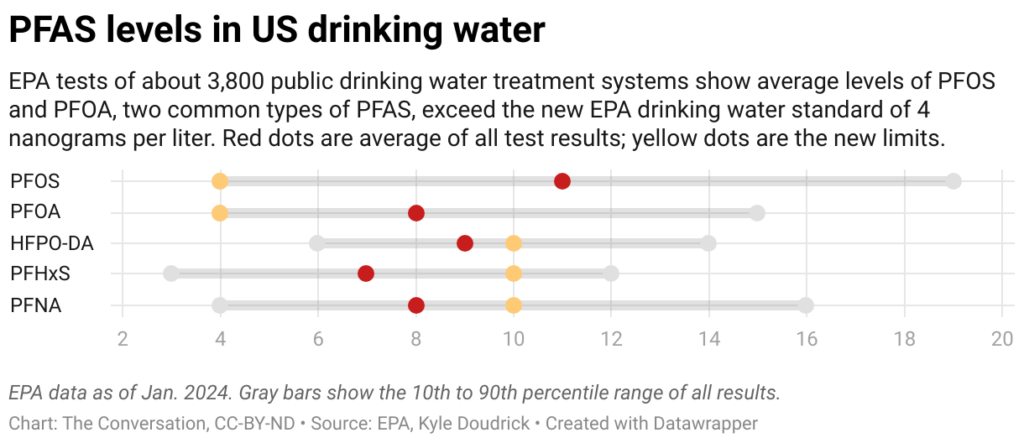

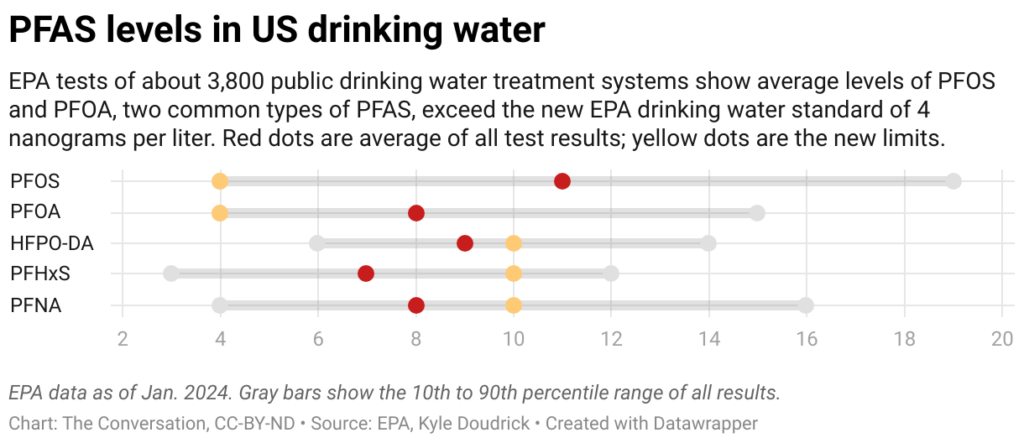

They can be found in the blood of most Americans and in many drinking water systems, which is why the Environmental Protection Agency in April 2024 finalized the first enforceable federal limits for six types of PFAS in drinking water systems. The limits—between 4 and 10 parts per trillion for PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA and GenX—are less than a drop of water in a thousand Olympic-sized swimming pools, which speaks to the chemicals’ toxicity. The sixth type, PFBS, is regulated as a mixture using what’s known as a hazard index.

Meeting these new limits won’t be easy or cheap. And there’s another problem: While PFAS can be filtered out of water, these “forever chemicals” are hard to destroy.

My team at the University of Notre Dame works on solving problems involving contaminants in water systems, including PFAS. We explore new technologies to remove PFAS from drinking water and to handle the PFAS waste. Here’s a glimpse of the magnitude of the challenge and ways you can reduce PFAS in your own drinking water:

Removing PFAS will cost billions per year

Every five years, the EPA is required to choose 30 unregulated contaminants to monitor in public drinking water systems. Right now, 29 of those 30 contaminants are PFAS. The tests provide a sense of just how widespread PFAS are in water systems and where.

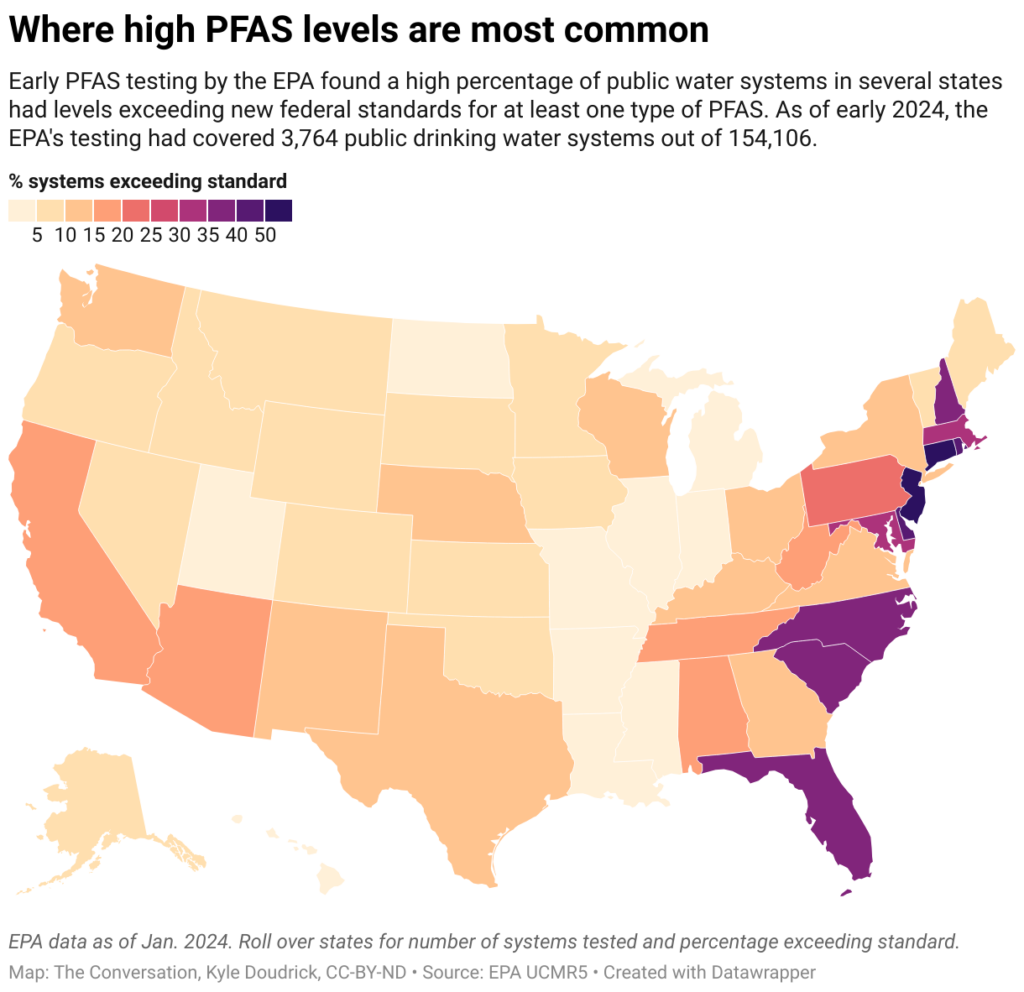

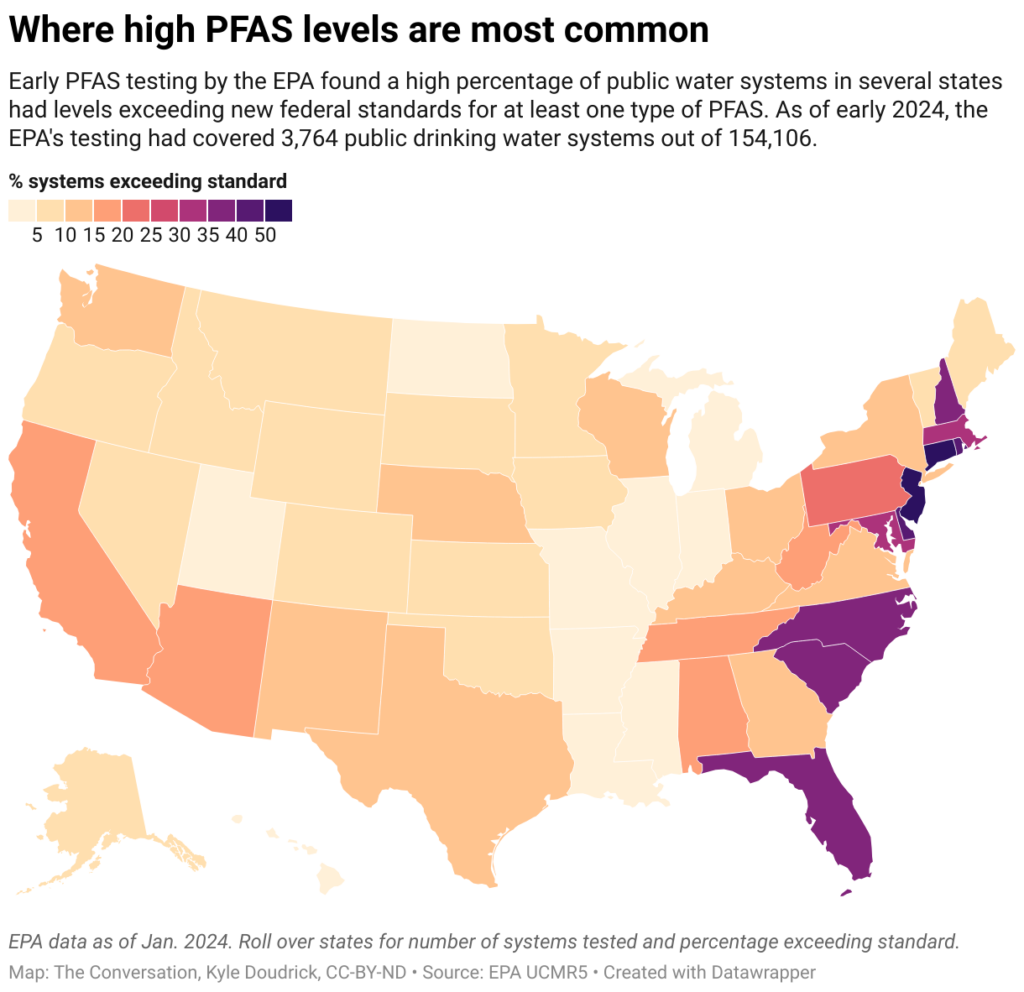

The EPA has taken over 22,500 samples from about 3,800 of the 154,000 public drinking water systems in the U.S. In 22% of those water systems, its testing found at least one of the six newly regulated PFAS, and about 16% of the systems exceeded the new standards. East Coast states had the largest percentage of systems with PFAS levels exceeding the new standards in EPA tests conducted so far.

Under the new EPA rules, public water systems have until 2027 to complete monitoring for PFAS and provide publicly available data. If they find PFAS at concentrations that exceed the new limits, then they must install a treatment system by 2029.

How much that will cost public water systems, and ultimately their customers, is still a big unknown, but it won’t be cheap.

The EPA estimated the cost to the nation’s public drinking water systems to comply with the news rules at about US$1.5 billion per year. But other estimates suggest the total costs of testing and cleaning up PFAS contamination will be much higher. The American Water Works Association put the cost at over $3.8 billion per year for PFOS and PFOA alone.

There are more than 5,000 chemicals that are considered PFAS, yet only a few have been studied for their toxicity, and even fewer tested for in drinking water. The United States Geological Survey estimates that nearly half of all tap water is contaminated with PFAS.

Some money for testing and cleanup will come from the federal government. Other funds will come from 3M and DuPont, the leading makers of PFAS. 3M agreed in a settlement to pay between $10.5 billion to $12.5 billion to help reimburse public water systems for some of their PFAS testing and treatment. But public water systems will still bear additional costs, and those costs will be passed on to residents.

Next problem: Disposing of ‘forever chemicals’

Another big question is how to dispose of the captured PFAS once they have been filtered out.

Landfills are being considered, but that just pushes the problem to the next generation. PFAS are known as “forever chemicals” for a reason—they are incredibly resilient and don’t break down naturally, so they are hard to destroy.

Studies have shown that PFAS can be broken down with energy-intensive technologies. But this comes with steep costs. Incinerators must reach over 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (1,000 Celsius) to destroy PFAS, and the possibility of creating potentially harmful byproducts is not yet well understood. Other suggested techniques, such as supercritical water oxidation or plasma reactors, have the same drawbacks.

So who is responsible for managing that PFAS waste? Ultimately the responsibility will likely fall on public drinking water systems.

The EPA on April 19, 2024, designated PFOA and PFOS as eligible contaminants for Superfund status, which means companies that are responsible for contaminating sites with those chemicals can be required to pay for cleanup. However, the EPA said it did not intend to go after wastewater treatment plants or public landfills.

Steps to protect your home from PFAS

Your first instinct might be to use bottled water to try to avoid PFAS exposures, but a recent study found that even bottled water can contain these chemicals. And bottled water is regulated by a different federal agency, the Food and Drug Administration, which has no standards for PFAS.

Your best option is to rely on the same technologies that treatment facilities will be using:

- Activated carbon is similar to charcoal. Like a sponge, it will capture the PFAS, removing it from the water. This is the same technology in refrigerator filters and in some water pitcher filters, like Brita or PUR. Note that many refrigerator manufacture’s filters are not certified for PFAS, so don’t assume they will remove PFAS to safe levels.

- Ion exchange resin is the same technology found in many home water softeners. Like activated carbon, it captures PFAS from the water, and you can find this technology in many pitcher filter products. If you opt for a whole house treatment system, which a plumber can attach where the water enters the house, ion exchange resin is probably the best choice. But it is expensive.

- Reverse osmosis is a membrane technology that only allows water and select compounds to pass through the membrane, while PFAS are blocked. This is commonly installed at the kitchen sink and has been found to be very effective at removing most PFAS in water. It is not practical for whole house treatment, but it is likely to remove a lot of other contaminants as well.

If you have a private well instead of a public drinking water system, that doesn’t mean you’re safe from PFAS exposure. Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources estimates that 71% of shallow private wells in that state have some level of PFAS contamination. Using a certified laboratory to test well water for PFAS can run $300-$600 per sample, a cost barrier that will leave many private well owners in the dark.

For all the treatment options, make sure the device you choose is certified for PFAS by a reputable testing agency, and follow the recommended schedule for maintenance and filter replacement. Unfortunately, there is currently no safe way to dispose of the filters, so they go in the trash. No treatment option is perfect, and none is likely to remove all PFAS down to safe levels, but some treatment is better than none.

This article, originally published April 17, 2024, has been updated with EPA’s Superfund declaration.

Kyle Doudrick, Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences, University of Notre Dame

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good. We publish trustworthy and informative articles written by academic experts for the general public and edited by our team of journalists.

Help Support Factkeepers!

{"id":null,"mode":"form","open_style":"in_place","currency_code":"USD","currency_symbol":"$","currency_type":"decimal","blank_flag_url":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-content\/plugins\/tip-jar-wp\/\/assets\/images\/flags\/blank.gif","flag_sprite_url":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-content\/plugins\/tip-jar-wp\/\/assets\/images\/flags\/flags.png","default_amount":500,"top_media_type":"none","featured_image_url":false,"featured_embed":"","header_media":null,"file_download_attachment_data":null,"recurring_options_enabled":true,"recurring_options":{"never":{"selected":true,"after_output":"One time only"},"weekly":{"selected":false,"after_output":"Every week"},"monthly":{"selected":false,"after_output":"Every month"},"yearly":{"selected":false,"after_output":"Every year"}},"strings":{"current_user_email":"","current_user_name":"","link_text":"Leave a tip","complete_payment_button_error_text":"Check info and try again","payment_verb":"Pay","payment_request_label":"Factkeepers.com","form_has_an_error":"Please check and fix the errors above","general_server_error":"Something isn't working right at the moment. Please try again.","form_title":"Help Support Factkeepers","form_subtitle":null,"currency_search_text":"Country or Currency here","other_payment_option":"Other payment option","manage_payments_button_text":"Manage your payments","thank_you_message":"Thank you for being a supporter!","payment_confirmation_title":"Factkeepers.com","receipt_title":"Your Receipt","print_receipt":"Print Receipt","email_receipt":"Email Receipt","email_receipt_sending":"Sending receipt...","email_receipt_success":"Email receipt successfully sent","email_receipt_failed":"Email receipt failed to send. Please try again.","receipt_payee":"Paid to","receipt_statement_descriptor":"This will show up on your statement as","receipt_date":"Date","receipt_transaction_id":"Transaction ID","receipt_transaction_amount":"Amount","refund_payer":"Refund from","login":"Log in to manage your payments","manage_payments":"Manage Payments","transactions_title":"Your Transactions","transaction_title":"Transaction Receipt","transaction_period":"Plan Period","arrangements_title":"Your Plans","arrangement_title":"Manage Plan","arrangement_details":"Plan Details","arrangement_id_title":"Plan ID","arrangement_payment_method_title":"Payment Method","arrangement_amount_title":"Plan Amount","arrangement_renewal_title":"Next renewal date","arrangement_action_cancel":"Cancel Plan","arrangement_action_cant_cancel":"Cancelling is currently not available.","arrangement_action_cancel_double":"Are you sure you'd like to cancel?","arrangement_cancelling":"Cancelling Plan...","arrangement_cancelled":"Plan Cancelled","arrangement_failed_to_cancel":"Failed to cancel plan","back_to_plans":"\u2190 Back to Plans","update_payment_method_verb":"Update","sca_auth_description":"Your have a pending renewal payment which requires authorization.","sca_auth_verb":"Authorize renewal payment","sca_authing_verb":"Authorizing payment","sca_authed_verb":"Payment successfully authorized!","sca_auth_failed":"Unable to authorize! Please try again.","login_button_text":"Log in","login_form_has_an_error":"Please check and fix the errors above","uppercase_search":"Search","lowercase_search":"search","uppercase_page":"Page","lowercase_page":"page","uppercase_items":"Items","lowercase_items":"items","uppercase_per":"Per","lowercase_per":"per","uppercase_of":"Of","lowercase_of":"of","back":"Back to plans","zip_code_placeholder":"Zip\/Postal Code","download_file_button_text":"Download File","input_field_instructions":{"tip_amount":{"placeholder_text":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like.","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like."},"invalid_curency":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like."}},"recurring":{"placeholder_text":"Recurring","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"How often would you like to donate this?"},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"How often would you like to donate this?"},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"How often would you like to donate this?"}},"name":{"placeholder_text":"Name on Credit Card","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter the name on your card."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Enter the name on your card."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Please enter the name on your card."}},"privacy_policy":{"terms_title":"Terms and conditions","terms_body":null,"terms_show_text":"View Terms","terms_hide_text":"Hide Terms","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"I agree to the terms."},"unchecked":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Please agree to the terms."},"checked":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"I agree to the terms."}},"email":{"placeholder_text":"Your email address","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your email address"},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Enter your email address"},"blank":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your email address"},"not_an_email_address":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Make sure you have entered a valid email address"}},"note_with_tip":{"placeholder_text":"Your note here...","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Attach a note to your tip (optional)"},"empty":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Attach a note to your tip (optional)"},"not_empty_initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Attach a note to your tip (optional)"},"saving":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Saving note..."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Note successfully saved!"},"error":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Unable to save note note at this time. Please try again."}},"email_for_login_code":{"placeholder_text":"Your email address","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."},"blank":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."}},"login_code":{"initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."},"blank":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."}},"stripe_all_in_one":{"initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your credit card details here."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your credit card details here."},"success":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your credit card details here."},"invalid_number":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card number is not a valid credit card number."},"invalid_expiry_month":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration month is invalid."},"invalid_expiry_year":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration year is invalid."},"invalid_cvc":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's security code is invalid."},"incorrect_number":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card number is incorrect."},"incomplete_number":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card number is incomplete."},"incomplete_cvc":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's security code is incomplete."},"incomplete_expiry":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration date is incomplete."},"incomplete_zip":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's zip code is incomplete."},"expired_card":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card has expired."},"incorrect_cvc":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's security code is incorrect."},"incorrect_zip":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's zip code failed validation."},"invalid_expiry_year_past":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration year is in the past"},"card_declined":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card was declined."},"missing":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"There is no card on a customer that is being charged."},"processing_error":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"An error occurred while processing the card."},"invalid_request_error":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Unable to process this payment, please try again or use alternative method."},"invalid_sofort_country":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The billing country is not accepted by SOFORT. Please try another country."}}}},"fetched_oembed_html":false}

{"date_format":"F j, Y","time_format":"g:i a","wordpress_permalink_only":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/removing-pfas-from-public-water-systems-will-take-billions-and-years-heres-what-you-can-do-till-then\/","all_default_visual_states":"inherit","modal_visual_state":false,"user_is_logged_in":false,"stripe_api_key":"pk_live_40P3DgGDAHEP1QtJ0nOU4nms5JYHI8GbQ05dYiB1S8OPP5oMSIpOCCeeIawOyeW6bWDkDMWdUeggbhxOQTSA6aedu00ROAbhXBd","stripe_account_country_code":"US","setup_link":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-admin\/admin.php?page=tip-jar-wp&mpwpadmin1=welcome&mpwpadmin_lightbox=do_wizard_health_check","close_button_url":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-content\/plugins\/tip-jar-wp\/\/assets\/images\/closebtn.png"}

![]()