“The flame of the Enlightenment is waning,” a journalist said to Günter Gass. “But,” he replied, “there is no other source of light.”

When I heard the news, my first reaction was, “Well, they finally got him.” Salman Rushdie has been a wanted man since Valentine’s Day 1989 when Iran’s dying supreme leader, the Ayatollah Khomeini (1902-1989), issued a fatwa (edict) instructing Muslims worldwide that they had a duty to kill Rushdie for blasphemy.

Rushdie has lived for more than 30 years in fear and nine in hiding, at dozens of temporary domiciles throughout the British Isles, under an assumed name and under the protection of British protection agents. In the first five months of his protective arrest, he was forced to move 56 times.

In recent years he relocated in New York, lived quietly in lower Manhattan, and attempted to resume something like a normal life. That was a calculated risk. Now he has paid the price.

The Rushdie Affair

The extraterritorial death sentence was issued by Khomeini on Radio Tehran in 1989 after worldwide protests erupted over the publication of Rushdie’s fourth novel, The Satanic Verses, a sprawling exploration of migration, marginality and identity, which contains one chapter (Rushdie now calls it “the notorious Mahound chapter”) treating Muhammad, the seventh-century founder of Islam, as a sometimes-fallible human being rather than an untouchable prophet. That was enough to touch off perhaps the most infamous book banning in the history of literature.

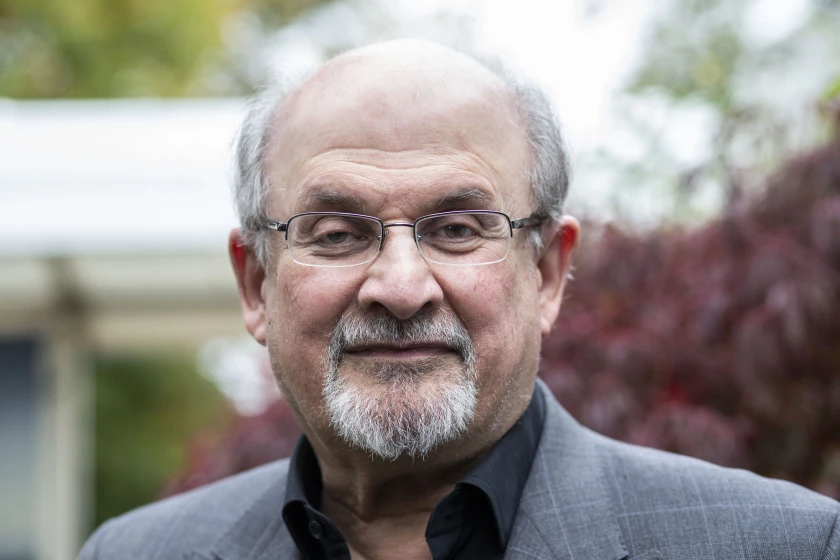

Earlier this month, on Aug. 12, Rushdie was about to address an audience at Lake Chautauqua, N.Y., when a 24-year-old man named Hadi Matar of Fairview, N.J., rushed the stage and stabbed him approximately a dozen times, mostly in the neck, puncturing an eye, damaging his liver and cutting the nerves in his arm. Rushdie was rushed to the hospital. He is expected to survive, though his agent has reported that his recovery will be slow and probably incomplete, and he may well lose his eye.

Author Salman Rushdie is tended to after he was attacked during a lecture, Friday, Aug. 12, 2022, at the Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, N.Y. Joshua Goodman/AP

Rushdie has written, “When a book leaves its author’s desk it changes. Even before anyone has read it, before eyes other than its creator’s have looked upon a single phrase, it is irretrievably altered. It has become a book that can be read, that no longer belongs to its maker. It has acquired, in a sense, free will. It will make its journey through the world and there is no longer anything the author can do about it.” “No longer belongs to its maker” is a profound understatement about The Satanic Verses, one of the most talked about books of the last hundred years as well as one of the least read. One of the myriad ironies of The Satanic Verses is that Rushdie regards it as the least political of his novels. But because the “Rushdie Affair” has never really been about the book, but rather what the existence of the book can be made to signify in the Islamic world, Rushdie’s tormenters discount anything he has to say either in explanation or defense of his art.

For Rushdie it is this simple: “A mullah with a long arm was reaching out across the world to squeeze the life out of him.”

Hadi Matar was not yet born when The Satanic Verses was published. I’d bet a fortune that Matar has never read the novel or anything else that Rushdie has written. (In a subsequent interview, he said he has read no more than two pages of the novel). Of the millions of fanatical fundamentalists worldwide who have denounced Rushdie, participated in protests, burned him in effigy, bombed bookstores and publishing houses, killed or attempted to kill his translators, and killed or attempted to kill even Muslim defenders of his work, not one in a million has ever sat down to read the novel and decide for themself what to make of it. This is standard practice among the book banners and book burners of the world. Indian member of parliament Syed Shahabuddin said, “I do not have to wade through a filthy drain to know what filth is.”

In the last 33 years, as many as 50 people have died because of the publication of The Satanic Verses. Most of them died in anti-Rushdie riots in Muslim cities, including a dozen in his hometown of Mumbai. His Japanese translator Hitoshi Igarashi was stabbed to death in 1991. Igarashi taught Islamic studies at a university near Tokyo. Rushdie’s Italian translator survived a knife attack, and in 1993 his Norwegian publisher was shot three times. He survived.

The Rise and Fall of Salman Rushdie

Rushdie is an Anglo-Indian novelist, born in Mumbai (formerly Bombay) in 1947, within months of Indian independence, which brought forth civil war and the partition of India and Pakistan. His father brought him to Great Britain when he was a boy. He attended Rugby and then King’s College, Cambridge, where he took a degree in history. He worked in the London advertising industry for a few years before the phenomenal success of his novel Midnight’s Children, about the birth of modern India, permitted him to devote full time to his writing. Midnight’s Children won Britain’s coveted Booker Prize in 1981. Rushdie was knighted for his services to literature in 2007.

Thirteen countries eventually banned The Satanic Verses, beginning with India. Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher refused to meet with him. Bookstores around the world, including in the United States, chose not to place the novel on their shelves. Carrying the controversial book in spite of the global threats, Cody’s Bookstore in Berkeley, Calif., was firebombed at 4:30 a.m. on Feb. 28, 1989. When Cody’s owner Andy Ross assembled his staff in the wake of the bombing, they voted unanimously to continue to carry the book. “It was the defining moment in my 35 years of bookselling,” Ross has written. “It was also the moment when I realized bookselling was a dangerous and subversive vocation; because, after all, ideas are powerful weapons.”

Although the literary world overwhelmingly closed ranks around Rushdie and defended his right to publish whatever he writes, a number of prominent writers have, at one time or another, turned on him, including one of the greatest literary critics of our time, George Steiner, and the dean of British historians Hugh Trevor-Roper. The novelist John le Carré wrote, “I don’t think it is given to any of us to be impertinent to great religions with impunity.” Le Carré accused Rushdie of “self-canonization.” When the former British foreign secretary Douglas Hurd, himself a novelist, was asked by the Evening Standard, “What was your most painful moment in government?” he replied, “Reading The Satanic Verses.” Ouch. The influential Muslim professor Fatima Meer said, “In the final analysis, it is the Third World that Rushdie attacks.”

The Brilliant (if Sometimes Tedious) Memoir

In 2012, Rushdie published a long memoir about his life under the shadow of a free-floating extraterritorial death sentence. I read Joseph Anton when it first appeared and I have been reading it again since the attack in New York. He crafted his underground nom de plume from the first names of two of his favorite authors, Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov. Joseph Anton is a fascinating and necessary document, must reading for anyone who believes in freedom of expression, including subversive, irreverent, sarcastic, even blasphemous expression. “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear,” George Orwell wrote. Henry Louis Gates Jr., has said, “Censorship is to art as lynching is to justice.”

In his memoir, Rushdie seeks to combat three notions. First, he rejects out of hand the view that he deliberately wrote a sensational and scandalous novel in a quest for fame and the bestseller list. Second, he rejects the idea that he knew or should have known exactly what he was doing in writing The Satanic Verses, and however appalling the Islamic reaction was, he brought it on himself. Third, he rejects the idea that he and his publishers should have gone straight into urgent damage control, that they should have withdrawn the book and apologized abjectly to the Islamic world.

A year into his ordeal, hoping to make the fatwa go away, Rushdie was persuaded to issue a kind of limited apology. After Iran’s President Ali Khamenei suggested that if Rushdie “apologizes and disowns the book, people may forgive him,” the author issued a statement saying: “I recognize that Muslims in many parts of the world are genuinely distressed by the publication of my novel. I profoundly regret the distress the publication has occasioned to the sincere followers of Islam. Living as we do in a world of many faiths, this experience has served to remind us that we must all be conscious of the sensibilities of others.” This was not enough. Nothing changed. Iran’s highest religious authorities declared, “Even if Salman Rushdie repents and becomes the most pious man of all time, it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has got, his life and wealth, to send him to Hell.” Rushdie later said issuing the “apology” was the greatest mistake of his life.

Author Sir Salman Rushdie at the Cheltenham Literature Festival on October 12, 2019 in Cheltenham, England, UK. STAR MAX/IPx

The human being Salman Rushdie who is revealed in Joseph Anton is not always very admirable. Like most writers, Rushdie is egotistical, self-righteous, thin-skinned, arrogant, self-pitying, paranoid, and full of himself. If his memoir is to be trusted, quarrels, including literary quarrels, have been a continuing fact of his life. Many Brits grew tired of his self-pitying martyrdom. He has apparently had lots of failed relationships with beautiful and headstrong women, including four failed marriages. As the underground years ground endlessly along, at times he exhibited signs of ingratitude toward the heroic and extremely expensive protection services provided for him by the British taxpayers. But all this is only part of the story. As the 636 pages of Joseph Anton abundantly reveal, Rushdie is capable of being charming, self-parodying, self-critical, and at times genuinely funny. His paranoia and self-pity are perhaps understandable given that he has spent the second half of his life under a death sentence and the withering scrutiny of friends and foes alike.

Among other things, Rushdie’s memoir is an important artistic manifesto. It is one of the best defenses of the freedom of the artist I have ever read. His publisher Viking Penguin was understandably shaken by the firestorm of controversy. Rushdie told a journalist, “How we responded to the controversy … would affect the future of free inquiry, without which there would be no publishing as we knew it, but also, by extension, no civil society as we knew it.” Rushdie believed that if Viking Penguin stood by him, “it would come to be remembered as one of the greatest chapters in the history of publishing, one of the grand principled defenses of liberty.” Self-serving? Maybe, but it is hard to disagree with his analysis. Viking Penguin gets a B- for its sometimes-wobbly support of its most famous author.

The Paradox of Freedom: With Artistic License Comes Risk

Literature is provocative. Literature is subversive. Literature is edgy. Literature is transgressive. Literature explores the boundaries of human character, impulse and behavior. In the western world, literature is regarded as specially licensed to nudge around things most of us would rather not face. We all know that censorship violates one of the sacred principles of the Enlightenment (“Madam, I disagree with what you say, but shall defend to the death your right to say it”), and that censorship through violence is particularly barbaric.

Still, artistic license carries with it certain risks. If you are John Lennon and in 1966 you say, “We’re more popular than Jesus now,” you can expect blowback, especially in a nation as overwhelmingly Christian as the United States at that time. More than 30 radio stations refused to play Beatles music. WAQY in Birmingham, Ala., hired a tree chipper and invited listeners to bring their Beatles merchandise for pulverization. Anti-Beatles clubs sprang up throughout the heartland. There were protests at some of the venues of the Beatles’ next U.S. tour. In fact, the controversy may have played a role in their decision to quit performing live altogether. Mark David Chapman eventually said the “Jesus” gaffe was a factor in his assassination of John Lennon on Dec. 8, 1980. This I doubt.

The Fatwa That Will Never End

What’s next for Salman Rushdie? Assuming he recovers, he’ll have to make a tough decision now. He can go back into hiding for whatever remains of his life (he’s 75). That seems unlikely. Or he can shrug this attack off, throw himself fatalistically back into the arena, continue to lead a life of high-risk freedom, and travel the world with a limp and an eye patch, reminding us all of what is at stake in human freedom no matter how much we may wish to look away. He is now a doubly marked man, a victim of censorship-by-violence, for the supposed blasphemies of a novel nobody reads. The Aug. 12 attack may bring on others, including from young Islamists who had never heard of Rushdie before.

The best thing we can do to show our solidarity with Rushdie and all other artists is to buy and read his books. Joseph Anton is must reading for anyone who is committed to freedom of expression and the sovereignty of art. To my mind, Midnight’s Children is his best novel. Controversy aside, the majority of serious readers find The Satanic Verses tough sledding and some have pronounced it unreadable. That’s not the best place to start. His young person’s novel, Haroun and the Sea of Stories, written during the fatwa ordeal at the request of his son Zafar, is delightful.

Republished with permission from Governing Magazine, by Clay S. Jenkinson

Governing

Governing: The Future of States and Localities takes on the question of what state and local government looks like in a world of rapidly advancing technology. Governing is a resource for elected and appointed officials and other public leaders who are looking for smart insights and a forum to better understand and manage through this era of change.