On the last street before leaving Jacksonville, there’s a dark brick one-story building that the locals know as the school for “bad” kids. It’s actually a tiny public school for children with disabilities. It sits across the street from farmland and is 2 miles from the Illinois city’s police department, which makes for a short trip when the school calls 911.

Administrators at the Garrison School call the police to report student misbehavior every other school day, on average. And because staff members regularly press charges against the children—some as young as 9—officers have arrested students more than 100 times in the last five school years, an investigation by the Chicago Tribune and ProPublica found. That is an astounding number given that Garrison, the only school that is part of the Four Rivers Special Education District, has fewer than 65 students in most years.

No other school district—not just in Illinois, but in the entire country—had a higher student arrest rate than Four Rivers the last time data was collected nationwide. That school year, 2017-18, more than half of all Garrison students were arrested.

Officers typically handcuff students and take them to the police station, where they are fingerprinted, photographed and placed in a holding room. For at least a decade, the local newspaper has included the arrests in its daily police blotter for all to see.

The students enrolled each year at Garrison have severe emotional or behavioral disabilities that kept them from succeeding at previous schools. Some also have been diagnosed with autism, ADHD or other disorders. Many have experienced horrifying trauma, including sexual abuse, the death of parents and incarceration of family members, according to interviews with families and school employees.

Getting arrested for behavior at school is not inevitable for students with such challenges. There are about 60 similar public special education schools across Illinois, but none comes anywhere close to Garrison in their number of student arrests, the investigation found.

The ProPublica-Tribune investigation—built on hundreds of school reports and police records, as well as dozens of interviews with employees, students and parents—reveals how a public school intended to be a therapeutic option for students with severe emotional disabilities has instead subjected many of them to the justice system.

It is “just backwards if you are sending kids to a therapeutic day school and then locking them up. That is not what therapeutic day schools are for,” said Jessica Gingold, an attorney in the special education clinic at Equip for Equality, the state’s federally appointed watchdog for people with disabilities.

Doors lead to classrooms at the Garrison School, a public special education school for students with severe emotional or behavioral disabilities. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

“If the school exists for young people who need support, to think of them as delinquents is basically the worst you could do. It’s counter to what should be happening,” Gingold said.

Because of the difficulties the students face in regulating their emotions, these specialized schools are tasked with recognizing what triggers their behavior, teaching calming strategies and reinforcing good behavior. But Garrison doesn’t even offer students the type of help many traditional schools have: a curriculum known as social emotional learning that is aimed at teaching students how to develop social skills, manage their emotions and show empathy toward others.

Tracey Fair, director of the Four Rivers Special Education District, said it is the only public school in this part of west central Illinois for students with severe behavioral disabilities, and there are few options for private placement. School workers deal with challenging behavior from Garrison students every day, she said.

Tracey Fair, director of the Four Rivers Special Education District, which runs the Garrison School, speaks at a November meeting of the district’s board. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

“There are consequences to their behavior and this behavior would not be tolerated anywhere else in the community,” Fair said in written answers to reporters’ questions.

Fair, who has overseen Four Rivers since July 2020, said Garrison administrators call police only when students are being physically aggressive or in response to “ongoing” misbehavior. But records detail multiple instances when staff called police because students were being disobedient: spraying water, punching a desk or damaging a filing cabinet, for example.

“The students were still not calming down, so police arrested them,” wrote Fair, speaking on behalf of the district and the school.

This year, the Tribune and ProPublica have been exposing the consequences for students when their schools use police as disciplinarians. The investigation “The Price Kids Pay” uncovered the practice of Illinois schools working with local law enforcement to ticket students for minor misbehavior. Reporters documented nearly 12,000 tickets in dozens of school districts, and state officials moved quickly to denounce the practice.

This latest investigation further reveals the harm to children when schools abdicate student discipline to police. Arrested students miss time in the classroom and get entangled in the justice system. They come to view adults as hostile and school as prison-like, a place where they regularly are confined to classrooms when the school is “on restriction” because of police presence.

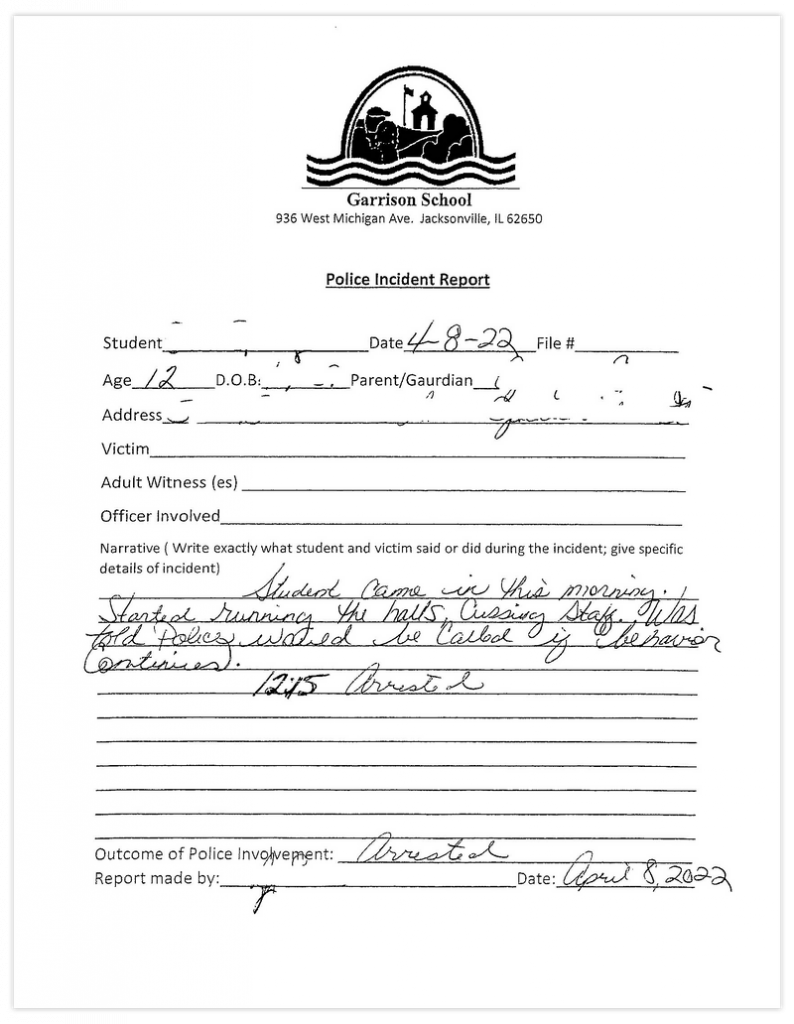

A “Police Incident Report” form used by the Garrison School details a student’s behavior and arrest. Credit: Obtained by ProPublica and Chicago Tribune; identifying information removed by the school.

U.S. Department of Education and Illinois officials have reminded educators in recent months that if school officials fail to consider whether a student’s behavior is related to their disability, they risk running afoul of federal law.

But unlike some other states, Illinois does not require schools to report student arrest data to the state or direct its education department to monitor police involvement in school incidents. Legislative efforts to do so have stalled over the past few years.

In response to questions from reporters about Garrison, Illinois Superintendent of Education Carmen Ayala said the frequent arrests there were “concerning.” An Illinois State Board of Education spokesperson said a state team visited the school this month to examine “potential violations” raised through ProPublica and Tribune reporting.

The team confirmed an overreliance on police and, as a result, the state will provide training and other professional development, spokesperson Jackie Matthews said.

“It is not illegal to call the police, but there are tactics and strategies to use to keep it from getting to that point,” Matthews said.

Ayala said educators cannot ignore their responsibility to help students work through behavioral issues.

“Involving the police in any student issue can escalate the situation and lead to criminal justice involvement, so calling the police should be a last resort,” she said in a written statement.

In 2018, Jacksonville police arrested a student named Christian just a few weeks into his first year at Garrison, when he was 12 years old. His “disruptive” behavior earlier in the day—he had knocked on doors and bounced a ball in the hallway—had led to a warning: “One more thing” and he would be arrested, a school report said. He then removed items from an aide’s desk and was “being disrespectful,” so police were summoned. They took him into custody for disorderly conduct.

Christian has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Now 16, he has been arrested at Garrison several more times and was sent to a detention center after at least one of the arrests, he and his mother said.

He stopped going to school in October; his mother said it’s heartbreaking that he’s not in class, but at Garrison, “it’s more hectic than productive. He’s more in trouble than learning anything.”

“If they call the police on you, you are going to jail,” Christian told reporters. “It is not just one coming to get you. It will be two or three of them. They handcuff you and walk you out, right out the door.”

Handcuffs and Holding Rooms

Just over an hour into the school day on Nov. 15, two police cars rushed into the Garrison school parking lot and stopped outside the front doors. Three more squad cars pulled in behind them but quickly moved on.

Principal Denise Waggener had called the Jacksonville police to report that a 14-year-old student had been spitting at staff members. When police arrived, one of the officers recognized the boy, because he had driven him to school that morning. The student had missed the bus and called police for help, according to a police report and 911 call.

School staff had placed the boy in one of Garrison’s small cinder-block seclusion rooms for “misbehavior,” police records show. A school worker told the officer she had been standing in the doorway of the seclusion room when the boy spit and it landed on her face, glasses and shirt.

The child “initially stated he did not spit at anyone, but then said he did spit,” according to the police report, “but instantly regretted doing so.” The report said the child “stated he knew right from wrong, but often had violent outbursts.”

The worker asked to press charges, and the officer arrested the boy for aggravated battery.

One officer told the child he was under arrest while another searched and handcuffed him. They put him in the back seat of a squad car, drove him to the police station, read him his rights and booked him. Officers told the boy the county’s probation department would contact him later, and then they dropped him off with a guardian, records show.

The Tribune and ProPublica documented and analyzed 415 of Garrison’s “police incident reports” dating to 2015 and found the school has called police, on average, once every two school days.

The reports, written by school staff and obtained through public records requests, describe in detail what happened up until the moment police were called. These narratives, along with recordings of 911 calls, show that school workers often summon police not amid an emergency but because someone at the school wants police to hold the child responsible for their behavior.

Jacksonville police respond in November to a call from a Garrison School administrator about a student’s misbehavior. Officers arrested the student. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

About half the calls were made for safety reasons because students had fled the school. Those students rarely were arrested. Students whom police did arrest were most often accused of aggravated battery and had been involved in physical interactions such as spitting or pushing; by state law, any physical interaction with a school employee elevates what would otherwise be a battery charge to aggravated battery. The next most common arrest reasons were disorderly conduct, resisting arrest and property damage.

The school once called police after a student was told he couldn’t use the restroom because he “had done nothing all morning,” records show. The boy got upset, left the classroom anyway and broke a desk in the hallway.

The school called police on a 12-year-old who was “running the halls, cussing staff.”

And the school called the police when a 15-year-old boy who was made to eat lunch inside one of the school’s seclusion rooms threw his applesauce and milk against the wall.

Police arrested them all.

“These students, I would imagine, feel like potential criminals under threat,” said Aaron Kupchik, a sociologist at the University of Delaware who studies punishment and policing in schools.

“We are taking the actions of young people, and, rather than trying to invest in solving real behavioral problems that are very difficult, we are just exposing them to the legal system and legal system consequences.”

Jacksonville Chief of Police Adam Mefford said officers respond to every 911 call from Garrison on the assumption it’s an emergency, and as many as five squad cars can respond. Police often find a child in a seclusion room, Mefford said.

Officers determine whether a law has been broken but leave the decision whether to press charges to the school staff, he said. Police sometimes issue tickets to Garrison students for violating local ordinances, though arrests are far more common.

“The school errs on the side of pressing charges,” Mefford said. “They typically have the student arrested.”

He wondered whether school administrators call police so frequently because it’s become a habit that’s difficult to stop. “The school has gotten used to us handling some of these problems,” Mefford said.

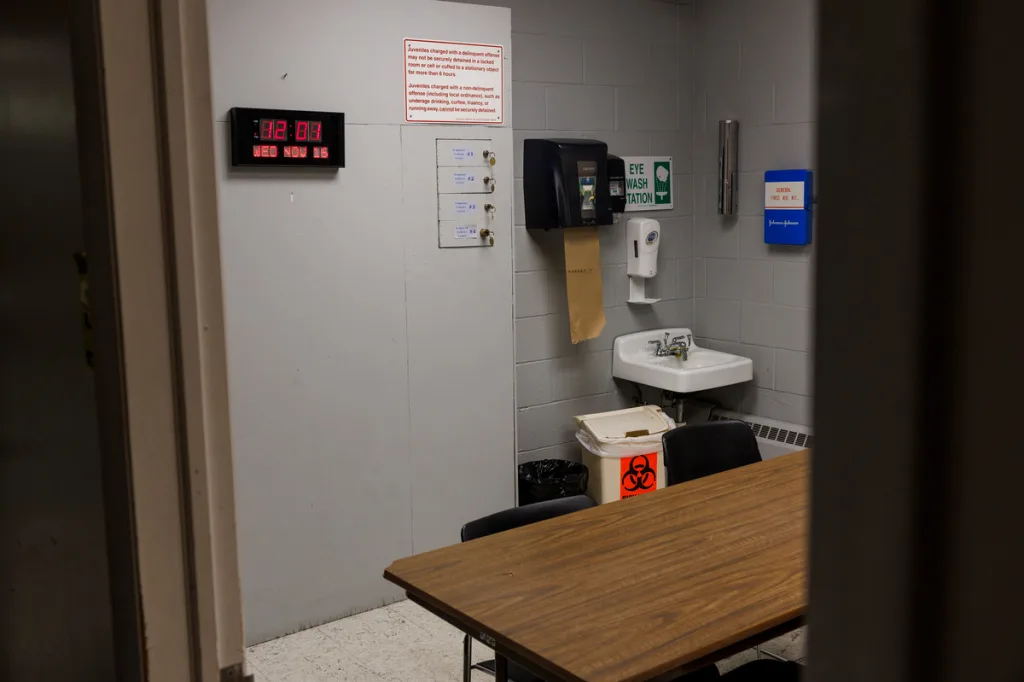

Once arrested, the students are taken to the police station until parents pick them up or an officer takes them home. One mother told reporters that her 10-year-old son, who has autism and ADHD, was “bawling, freaking out,” when she picked him up after he was booked at the jail.

Mefford said he tried to make the experience less traumatic by moving the booking process from the county detention facility to the police station in 2021. He also said police refer students and their families to services in the community, such as counseling or substance abuse help.

After they are booked, students are screened to determine if they should be sent to a juvenile detention facility. Most are assigned to an informal alternative to juvenile court that Morgan County court officials regularly use, said Tod Dillard, director of the county’s probation department.

Jacksonville police bring the Garrison School students they arrest to this booking area at the police station to be fingerprinted and photographed. Students often wait in the room for a guardian to pick them up. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

These young people avoid going to juvenile court, but the “probation adjustment” process also requires them to admit guilt and denies them a public defender. Students must periodically report to a probation officer, typically for a year.

Violating the probation terms, such as by skipping school or getting arrested again, could lead to juvenile delinquency charges. In a juvenile court case, a student’s record of previous informal probation can be used when considering bail or sentencing.

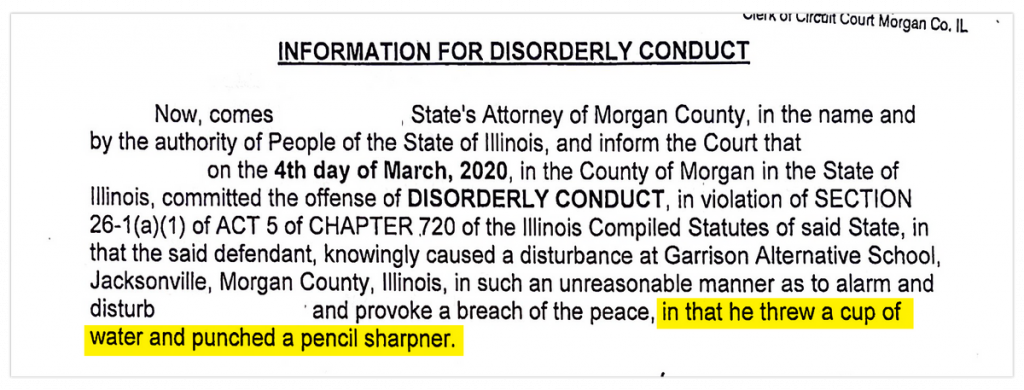

Garrison has some students who are 18 and older, and they can be charged as adults. In 2020, an 18-year-old Garrison student was arrested for disorderly conduct after he “caused a disturbance” when he threw a cup of water and punched a pencil sharpener, court records show. That student spent four days in jail and was held on $3,000 bail. He pleaded guilty and was ordered to pay $439 in court costs and $10 a month in probation fees.

An 18-year-old student was charged with disorderly conduct after an incident at the Garrison School. Credit: Obtained from the Morgan County Circuit Court. Redacted by ProPublica.

Even for younger students, juvenile charges related to Garrison can later have consequences in adult court. If they are arrested again after they turn 18, prior cases can be used to illustrate that they have a police record.

The boy who spit in anger this fall at Garrison now has an aggravated battery arrest on his record. Even Fair, the school’s director, found the decision to arrest the child troubling.

The day after the boy was taken into custody, Fair told reporters she knew the child had been arrested but said she did not know why school administrators had called police. Reporters told her it had been for spitting on one of her employees.

“That’s not arrestworthy. That is not what we should be about,” Fair said. In a later interview, after learning more about the incident, Fair said staff considered the student aggressive and said, “I guess they did what they thought was right.”

From Empathy to “Coercive Babysitting”

Bev Johns, a local educator, founded Garrison in 1981 with just two students—and a belief that with a caring staff and the right support, they could be successful.

The children had exhibited such disruptive behavior that staffers at their home schools felt ill-equipped to teach them. Her solution: Open a school designed to teach students not just academic subjects but how to manage their behavior. It became part of the Four Rivers Special Education District, a regional cooperative that today provides services to students in school districts across eight mostly rural counties.

The school was considered groundbreaking, and many of the techniques that Johns implemented at Garrison are still widely considered best practice for managing challenging behavior: giving students space when they’re upset, teaching them ways to manage their emotions and giving them choices rather than shouting demands.

Those techniques often involve trying to understand what’s driving a student’s behavior. A student shoving papers off their desk may feel overwhelmed and need assignments in smaller increments. A student struggling to sit still may need classwork that involves them moving around the room.

Taking the students’ disabilities into account when they misbehave is now a firmly entrenched concept in education. In fact, it’s federal law.

“There’s a requirement both in the law—and just morally—that kids with disabilities are not supposed to be punished for behaviors that are related to their disability, or caused by it, or caused by the school’s failure to meet their needs,” said Dan Losen, director of the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Johns, who led Garrison until 2003, has dedicated her career to these ideas. She published research about “the Garrison method” to help other educators, taught at a nearby college and continues to speak regularly at conferences.

“Choice is such a powerful strategy. It’s such an easy intervention,” Johns recently told a standing-room-only crowd at an Illinois special education convention in Naperville. And schools should look welcoming too, she said. “I see some schools that look like prisons. Why would a child want to go there?”

Buses from school districts throughout an eight-county region of rural Illinois bring students to the Garrison School on a morning in November. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

The Garrison of today isn’t a prison, but it relies on rules and methods meant to manage students.

In recent years, staffers sometimes took away students’ shoes to discourage them from fleeing, though Fair said that has not happened under her watch. Before a recent Illinois law banned locked seclusion in schools, Garrison workers used to shut students inside one of the school’s several seclusion rooms—staff members would stand outside and press a button to engage a magnetic lock. The doors have since been removed, but the “crisis rooms” are still used. The Four Rivers district reported to ISBE that workers had restrained or secluded students 155 times in the 2021-2022 school year—three times as many incidents as students.

“They would lock me in a concrete room and then close the door on me and lock it. I would freak out even worse,” said an 18-year-old named Max, who left the school in 2020.

Some of the school’s aides are assigned to one of two “crisis teams” of four employees each that respond to classrooms and can remove students who are upset, disobedient or aggressive.

Employees’ handwritten records describe several incidents where they confined a child to a small area inside the classroom. In one case, the crisis team made a “human wall” around a 14-year-old student who was wandering in the classroom, swearing and being disruptive. A 16-year-old student told reporters that school employees drew a box around his desk in chalk and told him not to leave the area or there would be consequences.

Charles Cropp, who has worked as part of crisis teams at Garrison on and off since 2009, said he and his colleagues try to help students learn how to calm down when they are upset. He said teams aim to help students learn how to manage their emotions but that sometimes the young people also need to be held “accountable” when they are physical or disruptive.

“I was one that never really cared to watch kids get escorted out in handcuffs,” said Cropp, who returned to the school full time in late November. “I never liked it but in the same sense, they have to learn when you graduate and you are an adult in the public, you can’t do those things.”

Garrison workers were recently trained in the Ukeru method, a crisis intervention system that uses blue shields to block students’ physical aggression in place of physical restraint. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

Jen Frakes, a board-certified behavior analyst who worked at Garrison in 2015-16, described the culture at Garrison as “coercive babysitting.” She said she never saw a situation that warranted arresting a student.

“It seemed more of a power dynamic of ‘You’ll either follow my rules or I will show you who’s in charge,’” said Frakes, who runs a Springfield business that helps schools and families learn to work through challenging behavior. “When I saw a kid get arrested, he was sitting underneath his desk calm and quiet, and they came in and arrested him.”

This isn’t how other schools similar to Garrison are handling difficult student behavior.

Reporters identified 57 other public schools throughout Illinois that also exclusively serve students with severe behavioral disabilities. To determine how often police were involved at those schools and why, reporters made public records requests to all of the schools and to the police or sheriff’s departments that serve each one. Reporters were able to examine police records for 50 schools.

The two schools with the most arrests during the last four school years had 16 and 18, respectively. At 23 of the schools, no students were arrested in that period; six schools had only one arrest.

By comparison, five students were arrested at Garrison by mid-November of this school year alone, according to school and police records.

John McKenna, an assistant professor specializing in special education at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, said arresting students not only criminalizes them but also takes them out of the classroom.

“Kids are supposed to be receiving instruction and support and not opportunities to enter the school-to-prison pipeline,” he said.

“If you don’t provide kids with academic instruction, particularly those with behavior and emotional needs, the gaps between their performance and the peers who don’t have disabilities grows exponentially and sets them up for failure,” McKenna said.

The fact that Garrison students have disabilities that may explain some of their behavior appears to be lost on many of the officials who encounter them in the justice system; some described Garrison as a school for delinquents, not disabled children. A public defender tasked with representing students in juvenile court described the children as having been “kicked out” of their regular schools. An assistant state’s attorney thought students at Garrison had been “expelled” from traditional schools. Neither of those descriptions is accurate.

Rhea Welch, who worked under Johns and retired in 2016, said that during her 26 years as a teacher at Garrison it was not a place that relied heavily on police. “You don’t want your kids arrested, for heaven’s sake. You want to be able to work with them so that doesn’t happen, so they’re more in control,” she said.

For Johns, Garrison is no longer the school she remembers. Students need positive feedback, she said, not constant reprimands from and clashes with the adults they are supposed to trust.

“I always say when you’re having trouble with a child, the first place you look is yourself,” she said.

Johns read some of the school’s recent police incident reports and said she found them “bothersome,” adding, “It’s obviously hard for me to watch what’s happened.”

“I Did Everything I Could to Get Him Out”

Gabe, a 12-year-old boy with autism, likes to share with anyone who will listen all the details of his Pokemon collection and has gotten good at using online translators to read the cards with Japanese lettering on them. His stepmother, Lena, said that over the years Gabe has learned to ask for what he needs. When he gets overstimulated at home, he asks for space by saying: “I need you to back up.”

(When using the last name of a parent would identify the student—and in doing so, create a publicly available record of the student’s arrest—ProPublica and the Tribune are referring to the parent by first name only.)

After an incident at the Garrison School, Gabe and his family decided he couldn’t go back. Shown with his father, Billy, and stepmother Lena, Gabe, who is 12 and has autism, now goes to a school 90 minutes away. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

Gabe ended up at Garrison in 2019 after having difficulty in traditional schools. He will sometimes yell and lash out when frustrated.

Lena said school officials asked her to pick up Gabe if he got upset. “I would hear Gabe screaming, and then heard them screaming back at him,” she said. “He’d say, ‘Leave me alone! Leave me alone!’ And they’d still get up in his face.”

And then one day, Gabe and Lena said, school workers barricaded him at his desk by pushing filing cabinets around it. He pushed over one of the cabinets while trying to get away, and the school called the police, Lena said.

“We had to pick up our 10-year-old at the police station,” Lena said. “I would freak out if I got boxed in with filing cabinets.”

It got so that Gabe would wake up angry and not want to go to school.

“That school is at the bottom of the food chain. If you got all the schools in the world, they would be at the bottom of the food chain. The workers there are mean,” said Gabe.

Other parents described their children becoming angrier, more withdrawn; the students dreaded going to school at Garrison. Some families begged their home districts to find another school for them.

“It was like hell,” said one mother, who said her son was miserable while he was a student there. “I did everything I could to get him out.” Her son attended Garrison for about five years before she got him returned to his home school. He is in his first year of college now.

Michelle Prather, whose daughter Destiny attended Garrison from fifth grade until she graduated in 2021, said school employees threatened to call police over minor missteps: throwing a piece of paper, or pushing a desk.

“She would walk out of a room and they’d say, ‘We’re going to call police,’” Prather said. Destiny was arrested at least once after she shoved an aide while trying to leave a classroom.

Prather and other caregivers said watching their children be arrested over and over was troubling, but it was also upsetting to realize that the school wasn’t providing the support services the students needed.

Destiny has intellectual disabilities and ADHD as well as acute spina bifida, a defect of the spine. Because of her medical condition, Destiny had difficulty sensing when she needed to use the restroom. She would sometimes get up from her desk and tell staff that she urgently needed to go.

“They would say, ‘No you don’t,’” said her mother. “She would have accidents. I would have to bring her clothes.”

Destiny, 19, who graduated from Garrison in 2021, plays with her family’s dog inside their home. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

Madisen Hohimer, who is now 22 and working as a bartender, said she transferred to Garrison in sixth grade when her home school recommended it. She remembers Garrison as a place that failed to help her. Hohimer said she frequently ran away from the school and employees took her shoes to try to keep her from fleeing.

“I was never involved with the police before Garrison. I started mostly acting out when I got sent over there because I felt like I had nobody,” she said. One time, she said, she swung and kicked at staff after they cornered her in a seclusion room. She wound up being arrested for aggravated battery.

Just weeks before Hohimer was set to graduate, she left for good. “I wish they would have found a way to help me,” she said.

After Gabe’s filing cabinet incident, his parents kept him home until he could be placed at a private therapeutic school three counties away. He’s been going there since last year.

“It’s an hour and a half ride and he’d rather do that than go to Garrison,” said Lena, a nursing student. He’s thriving there, she said, and noted that the school has never called police about Gabe’s behavior.

At their home in Jacksonville, Gabe shows his mother, Lena, a record player he made at school out of a cup and paper clip. Credit: Armando L. Sanchez/Chicago Tribune

But one of Lena’s other children, Nathan, remained at Garrison.

Then one morning in late September, she got a text from her son:

“I’M AT THE POLICE STATION THERE GOING TO GET MY FINGERPRINTS AND TAKE A PICTURE OF ME AND BRING ME BACK TO THE HOUSE.”

Nathan, who was 14 at the time, had been arrested after he hit a classmate and then shoved an aide who was trying to physically keep him in the classroom, according to a school report. He then left the school. In a 911 call, a school administrator asked police to find Nathan and also to come to the school “because a staff member will probably press charges.”

Nathan’s family decided not to send him back to Garrison. He’s taking classes online instead.

“That was my worst mistake, putting either of my kids in Garrison,” Lena said. “If I could take it back, I would.”

No One Watching

Warning signs that Garrison was punishing students with policing have been there for years, waiting for someone to take notice.

Since as far back as 2011, the federal government has published data online about police involvement and arrests at schools. That year, the data showed, Garrison called police on 54% of its students and 14% were arrested. Three subsequent publications of similar data show the arrest rate climbing each time—until, in 2017-18, more than half of Garrison’s students were arrested.

Though the federal data could have raised red flags, Illinois does not collect data on police involvement in schools and does not require that the state education board monitor it. The state does monitor other punitive practices in schools, such as their numbers of suspensions and expulsions, and requires schools to make improvements when the data shows excessive use.

Illinois legislation that would have required ISBE to collect data annually on school-related arrests and other discipline stalled last year.

The state board, however, has issued guidance about involving police in school discipline. Earlier this year, ISBE and the state attorney general’s office told school districts across the state to use social workers, mental health professionals and counselors—not police—to create a “positive and safe school climate.”

Before last week, no one from ISBE had been to Garrison for at least the last seven school years. There had been no complaints that would have triggered a monitoring visit, said Matthews, the state board spokesperson.

Garrison has its own school board, and it—not the state board—is responsible for monitoring the school, including police activity, ISBE officials said. The school board is made up of representatives from some of the 18 school districts that rely on Four Rivers for special education staffing and placements at Garrison.

The board president, Linda Eades, said after a November board meeting that she couldn’t answer questions about the police involvement at Garrison and described the board as hands-off. “We don’t get down in the trenches,” she said.

Fair, the district’s director, said she is trying to understand the scope of police involvement at Garrison and is “digging into” school reports. “I’m trying so hard. It’s a lot of stuff to change,” she said in an interview. “There are a lot of things that need to improve.”

Earlier this year, Garrison was awarded a $635,000 “Community Partnership Grant” through ISBE for training to help students with their behavioral and mental health needs and help schools reduce their reliance on punitive discipline.

Some of the grant money has been used to pay for training in Ukeru, a method of addressing physical aggression that doesn’t involve physically restraining a child.

The Ukeru method focuses on training workers in how to prevent challenging behavior from becoming a crisis and uses soft blue pads to block kicks and punches if necessary. Garrison workers were trained in the method in October; blue pads are now propped up in the hallways in the building.

Starting two weeks ago, Fair said, the school began using its two social workers and a social work intern in a new way. One of the social workers is now available to go into a classroom when a student needs help, providing a way to intervene before behavior escalates into a crisis. Fair said she also plans to incorporate social emotional learning into the curriculum.

School administrators mentioned the Ukeru training and some of Garrison’s latest efforts at the November board meeting, which lasted about 20 minutes. Fair said the school had begun to monitor police involvement and arrests and said she is trying to “boost up some of the supports for the kids.”

Her priority now, she assured them, is to “really help make it a therapeutic place for the kids.”

That’s what it was always supposed to be.

Republished with permission from ProPublica, by

ProPublica

ProPublica is an independent, nonprofit newsroom that produces investigative journalism with moral force. They dig deep into important issues, shining a light on abuses of power and betrayals of public trust — and they stick with those issues as long as it takes to hold power to account.

With a team of more than 100 dedicated journalists, ProPublica covers a range of topics including government and politics, business, criminal justice, the environment, education, health care, immigration, and technology. They focus on stories with the potential to spur real-world impact. Among other positive changes, their reporting has contributed to the passage of new laws; reversals of harmful policies and practices; and accountability for leaders at local, state and national levels.