Of all the subjects taught in the nation’s public schools, few have generated as much controversy of late as the subjects of racism and slavery in the United States.

The attention has come largely through a flood of legislative bills put forth primarily by Republicans over the past year and a half. Commonly referred to as anti-critical race theory legislation, these bills are meant to restrict how teachers discuss race and racism in their classrooms.

One of the more peculiar byproducts of this legislation came out of Texas, where, in June 2022, an advisory panel made up of nine educators recommended that slavery be referred to as “involuntary relocation.”

The measure ultimately failed.

As an educator who trains teachers on how to educate young students about the history of slavery in the United States, I see the Texas proposal as part of a disturbing trend of politicians seeking to hide the horrific and brutal nature of slavery—and to keep it divorced from the nation’s birth and development.

The Texas proposal, for instance, grew out of work done under a Texas law that says slavery and racism can’t be taught as part of the “true founding” of the United States. Rather, the law states, they must be taught as a “failure to live up to the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”

To better understand the nature of slavery and the role it played in America’s development, it helps to have some basic facts about how long slavery lasted in the territory now known as the United States and how many enslaved people it involved. I also believe in using authentic records to show students the reality of slavery.

Before the Mayflower

Slavery in what is now known as the United States is often traced back to the year 1619. That is when—as documented by Colonist John Rolfe—a ship named the White Lion delivered 20 or so enslaved Africans to Virginia.

As for the notion that slavery was not part of the founding of the United States, that is easily refuted by the U.S. Constitution itself. Specifically, Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1 prevented Congress from prohibiting the “importation” of slaves until 1808—nearly 20 years after the Constitution was ratified—although it didn’t use the word “slaves.” Instead, the Constitution used the phrase “such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit.”

Congress ultimately passed the “Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves,” which took effect in 1808. Although the act imposed heavy penalties on international traders, it did not end slavery itself nor the domestic sale of slaves. Not only did it drive trade underground, but many ships caught illegally trading were also brought into the United States and their “passengers” sold into slavery.

The last known slave ship—the Clotilda—arrived in Mobile, Alabama, in 1860, more than half a century after Congress outlawed the importation of enslaved individuals.

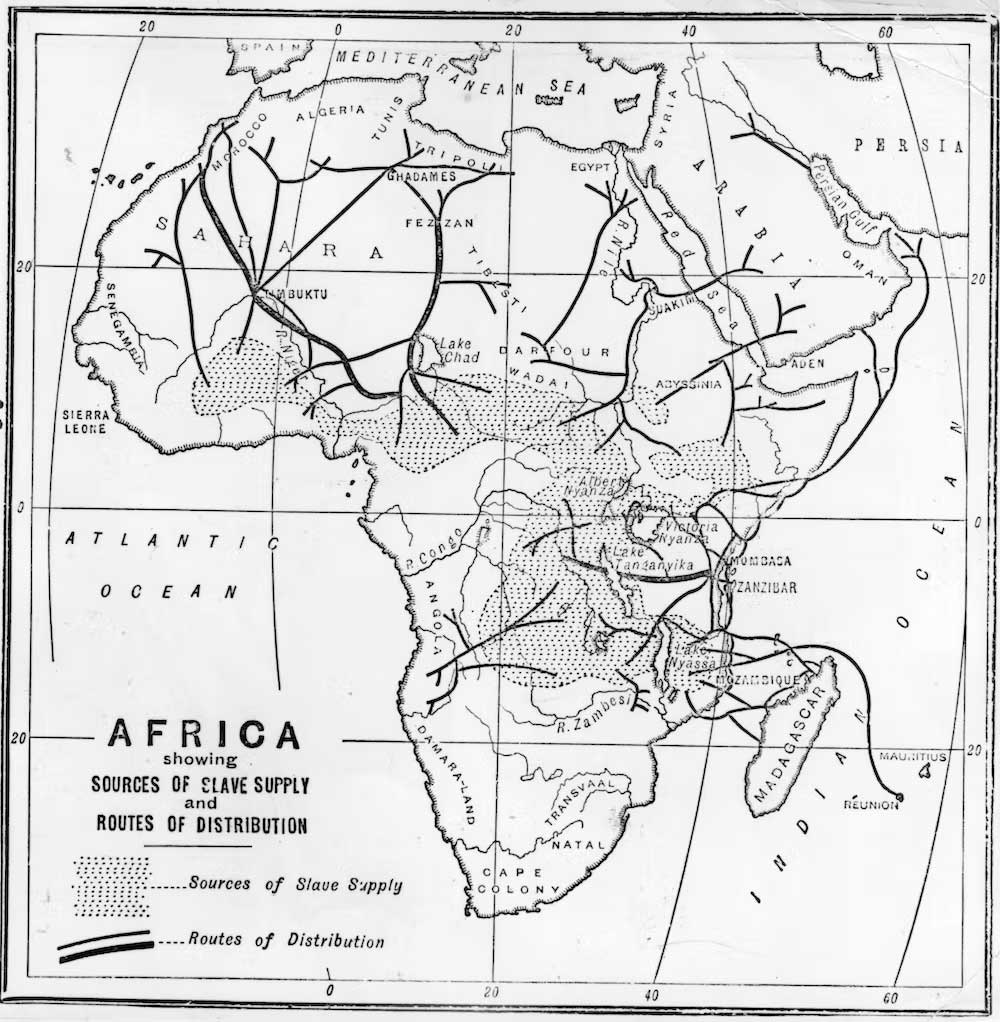

An 1880 map shows where enslaved people originated from and in which directions they were forced out. Hulton Archive/Stringer via Getty Images

According to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade database, which derives it numbers from shipping records from 1525 to 1866, approximately 12.5 million enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas. About 10.7 million survived the Middle Passage and arrived in North America, the Caribbean and South America. Of these, only a small portion—388,000—arrived in North America.

Most enslaved people in the United States, then, entered slavery not through importation or “involuntary relocation,” but by birth.

From the arrival of those first 20 so enslaved Africans in 1619 until slavery was abolished in 1865, approximately 10 million slaves lived in the United States and contributed 410 billion hours of labor. This is why slavery is a “crucial building block” to understanding the U.S. economy from the nation’s founding up until the Civil War.

The Value of Historical Records

As an educator who trains teachers on how to deal with the subject of slavery, I don’t see any value in politicians’ restricting what teachers can and can’t say about the role that slaveholders—at least 1,800 of whom were congressmen, not to mention the 12 who were U.S. presidents—played in the upholding of slavery in American society.

What I see value in is the use of historical records to educate schoolchildren about the harsh realities of slavery. There are three types of records that I recommend in particular.

1. Census Records

Since enslaved people were counted in each census that took place from 1790 to 1860, census records enable students to learn a lot about who specifically owned slaves. Census records also enable students to see differences in slave ownership within states and throughout the nation.

The censuses also show the growth of the slave population over time—from

697,624 during the first census in 1790, shortly after the nation’s founding, to 3.95 million during the 1860 census, as the nation stood at the verge of civil war.

2. Ads For Runaway Slaves

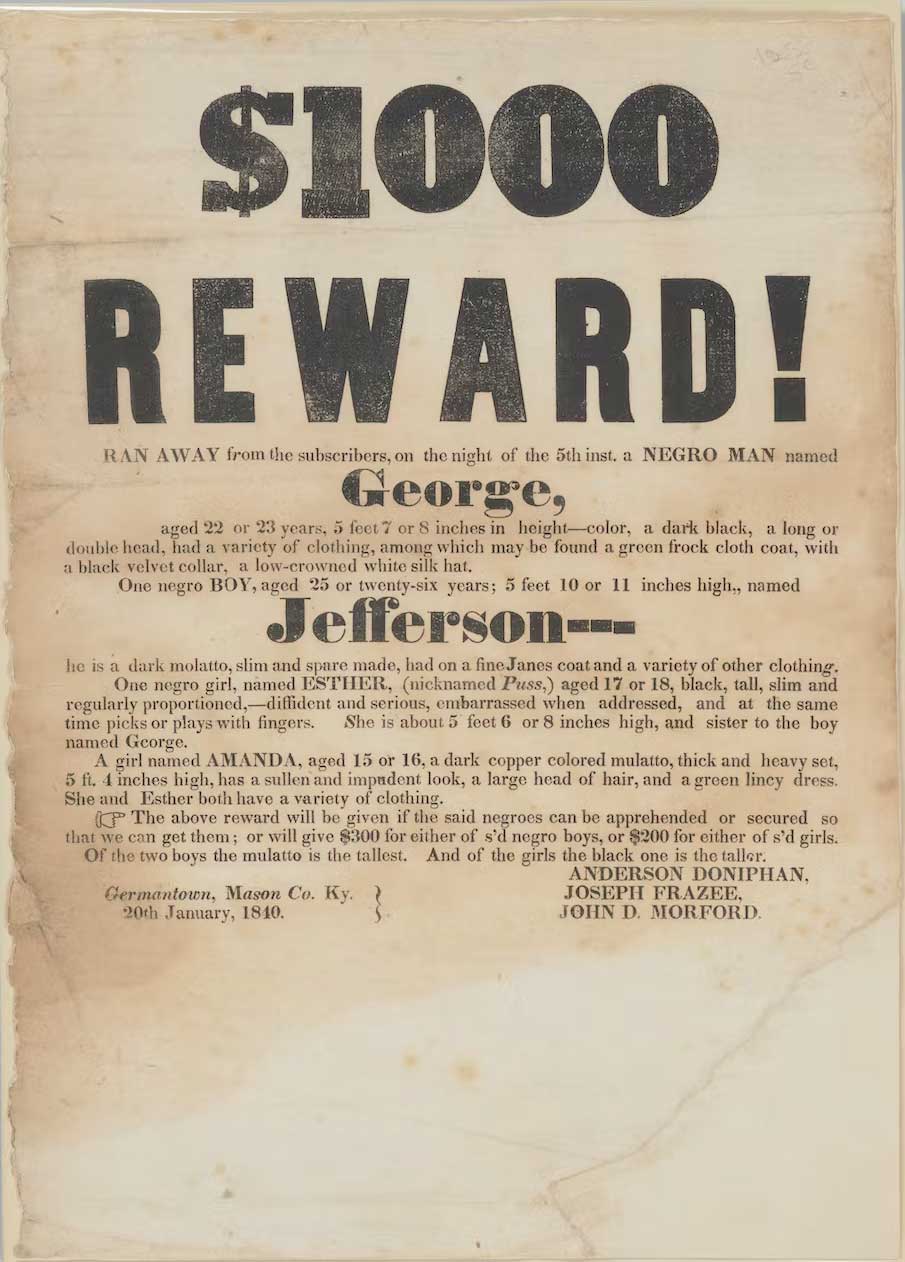

Advertisements for fugitive slaves offer a glimpse into their lives.

Few things speak to the horrors and harms of slavery like ads that slave owners took out for runaway slaves.

It’s not hard to find ads that describe fugitive slaves whose bodies were covered with various scars from beatings and marks from branding irons.

For instance, consider an ad taken out on July 3, 1823, in the Star, and North-Carolina State Gazette by Alford Green, who offers $25 for a fugitive slave named Ned, whom he described as follows:

“… about 21 years old, his weight about 150, well made, spry and active tolorably fierce look, a little inclined to be yellow, his upper fore teeth a little defective, and, I expect, has some signs of the whip on his hips and thighs, as he was whipped in that way the day before he went off.”

Advertisements for runaway slaves can be accessed via digital databases, such as Freedom on the Move, which contains more than 32,000 ads. Another database—the North Carolina Runaway Slave Notices project—contains 5,000 ads published in North Carolina newspapers from 1751 to 1865. The sheer number of these advertisements sheds light on how many enslaved Black people attempted to escape bondage.

3. Personal Narratives From the Enslaved

Though they are few in number, recordings of interviews with formerly enslaved people exist.

Some of the interviews are problematic for various reasons. For instance, some of the interviews were heavily edited by interviewers or did not include complete, word-for-word transcripts of the interviews.

Yet the interviews still provide a glimpse at the harshness of life in bondage. They also expose the fallacy of the argument that slaves—as one slave owner claimed in his memoir—“loved ‘old Marster’ better than anybody in the world, and would not have freedom if he offered it to them.”

For instance, when Fountain Hughes—a descendant of a slave owned by Thomas Jefferson who spent his boyhood in slavery in Charlottesville, Virginia—was asked if he would rather be free or enslaved, he told his interviewer:

“You know what I’d rather do? If I thought, had any idea, that I’d ever be a slave again, I’d take a gun and just end it all right away, because you’re nothing but a dog. You’re not a thing but a dog. A night never come that you had nothing to do. Time to cut tobacco? If they want you to cut all night long out in the field, you cut. And if they want you to hang all night long, you hang tobacco. It didn’t matter about you’re tired, being tired. You’re afraid to say you’re tired.”

It’s ironic, then, that when it comes to teaching America’s schoolchildren about the horrors of American slavery and how entrenched it was in America’s political establishment, some politicians would prefer to shackle educators with restrictive laws. What they could do is grant educators the ability to teach freely about the role the slavery played in the forming of a nation that was founded—as the Texas law states – on principles of liberty and equality.![]()

Republished with permission from The Conversation, by Raphael E. Rogers, Professor of Practice in Education, Clark University

The Conversation

The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good. We publish trustworthy and informative articles written by academic experts for the general public and edited by our team of journalists.