There seems to be no sense of shame or its cousin, guilt, in our time.

Conspiracy theorist Alex Jones tormented the parents of Sandy Hook’s murdered children by spreading the lie that the massacre was faked. The families sued. As the jury’s decision ordering Jones to pay almost US$1 billion to them was read in court on Oct. 12, 2022, Jones, appearing online from his studio, was “laughing and mocking the amounts being awarded,” NBC News reported.

GOP Georgia Senate candidate Herschel Walker, resolutely anti-abortion—with “no exception” for rape, incest or the life of the mother—denies allegations that he paid for a girlfriend’s abortion. Missouri Republican Sen. Josh Hawley riled up the Capitol rioters with a clenched fist salute on Jan. 6, 2021—and then ran from those same rioters when they invaded the Capitol.

While Republicans are by far the most prominently shameless among politicians, the condition is bipartisan in some areas. Democrats and Republicans showed up on a long list of legislators caught violating a law that requires them to disclose stock trading.

Shame and guilt seem equally foreign to many politicians and public figures these days. But here is what is different now from those in the past who behaved badly: Where once the lack of guilt and shame would have been cloaked by a veneer of virtuousness, today’s shameless see no need for that veil of hypocrisy.

For millennia, hypocrisy was the sneaky cloak of choice for miscreants. They used it to signal respect for society by pretending to play within its rules.

Now, they smirk. Hypocrisy is old-fashioned and, apparently, unnecessary.

An image of Sen. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., raising his fist to protesters outside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, is displayed on July 21, 2022, during a hearing by the House Select Committee to investigate the Jan. 6 attack. Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images

‘Willful Dissembling’

The Greek verb from which we derive “hypocrisy” and “hypocrite” originally meant “to respond.” Over time, this verb and its cognate noun acquired a theatrical context: a response or speech onstage. So in ancient times a hypocrite was someone playing a part; but the term was morally more or less neutral.

By the time of the New Testament, the word “hypocrite” had acquired the sense of willful dissembling, of playing a part with an intention to deceive. The role enacted involved assuming a good quality that in reality didn’t exist.

In Matthew 23:25-27, Christ inveighs against the “scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites!” who are “like unto whited sepulchers, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men’s bones, and of all uncleanness.” Their spotless exteriors conceal inner foulness.

Hypocrisy, then, suggests a disconnect between good qualities such as virtue, courage, or generosity and the corresponding vices—corruption, cowardice, greed—which a shiny surface conceals.

Victorian novels are rich in examples of hypocrites, who are sometimes villains and sometimes more or less amusing minor characters. Dickens’ novels offer a gallery of businessmen, clergymen, schoolmasters and others who present respectable exteriors but who in their private lives—and sometimes in public, too—are selfish and cruel.

Dickens had a genius for inventing appropriate names for such people. A few examples include Mssrs. Pecksniff, Murdstone, Veneering and Pumblechook, which furnish entertaining clues to the moral texture of these characters.

Naturally, readers thirst to see these Victorian hypocrites humbled, exposed—in a word, shamed. And the definition of “shame” in the Oxford English Dictionary turns out to have a distinctly Victorian flavor: “the painful emotion arising from the consciousness of something dishonoring, ridiculous, or indecorous to one’s own conduct or circumstances … or of being in a situation which offends one’s sense of modesty or decency.”

Most of the hypocrites encountered in Victorian novels are unmasked or humbled in the end. Though not all; Uriah Heep and Littimer, in “David Copperfield,” both exposed as villains near the end of the novel, are last glimpsed as model inmates in a creepy panopticonlike prison, as smarmy and sanctimonious as ever. They’re jailed, but not humbled.

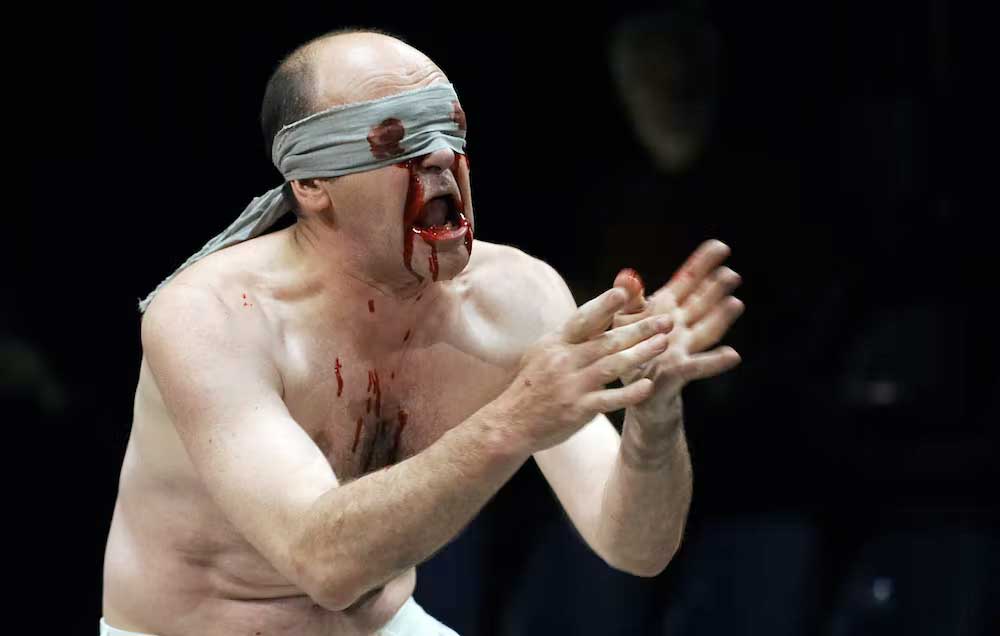

When Oedipus learns he killed his father and married his mother, he gouges out his eyes in shame, as depicted in this theatrical play presented at the 63rd Avignon International Theatre festival in France in 2009. Anne-Christine Poujoulat/AFP via Getty Images

No More Dissonance

Moving from the 19th century to the 21st, the bad behavior currently on display is a little different from the Victorian version, or from the whited sepulchers of the Gospel passage.

Hypocrisy, from the language in Matthew to the villainy of a Murdstone, always used to suggest a disconnect or dissonance between what was seen in public and what was really lurking underneath. But today, there seems no such clear line of demarcation.

To begin with, there’s no firm sense of truth. What the record shows—videos, transcripts, recordings—often fails to convince at least one side of the public if it’s condemned by the perpetrator as a witch hunt or fake news. Journalist Carlos Lozada, in an illuminating recent essay titled “The Inside Joke That Became Trump’s Big Lie,” called Donald Trump’s false claim that he won the 2020 election “a classic Trumpian projection … the lie is true and the truth is fake.” The description applies perfectly to the appalling lies of Alex Jones.

In such a topsy-turvy world, there’s no such thing as a hypocrite. Lozada points out that rather than hiding their rottenness beneath a show of virtue, the people whose antics we hear about daily seem to flaunt their true colors, if “true” is the right word. Their bad behavior is now acceptable, so it needs no disguise.

The moral balance encountered in Victorian novels, where hypocrites generally come to grief, now seems obsolete, almost a quaint relic. Greek tragedies don’t seem relevant either.

In Greek tragedy, the hero may make a mistake or be caught in an untenable situation. He may make a terrible decision that destroys others or himself. He may go mad and then recover his senses to view with horror the destruction he has caused. He may blame the gods for the devastation that has taken place.

But I can’t think of a case in which he pretends to be something he isn’t.

And shame is a key emotion in many tragedies. When Oedipus discovers he has committed the crimes whose perpetrator he has been pursuing, he blinds and exiles himself. In other tragedies, Ajax and Heracles unwittingly do terrible damage; when they recover their senses, they punish themselves.

The notion of hypocrisy seems to have come full circle, returning to its theatrical connotations, where a hypocrite was someone simply playing a part. We’re back to acting after all, and the stage is our country.![]()

Republished with permission from The Conversation, by Rachel Hadas, Professor of English, Rutgers University – Newark

The Conversation

The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good. We publish trustworthy and informative articles written by academic experts for the general public and edited by our team of journalists.