Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021. Image: Jan 6th Comittee

Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021. Image: Jan 6th Comittee

The twisted and convoluted appeal filed by Trump's attorneys to the Supreme Court, seeking to overturn his ban from the Colorado ballot has now been answered by the voters bringing the original case.

Republished with permission from The Conversation, by Wayne Unger, Quinnipiac University

The plaintiffs seeking to remove former President Donald Trump from Colorado’s 2024 presidential election ballots filed their brief to the U.S. Supreme Court on Jan. 26, 2024. They asked the court to uphold the ruling by Colorado’s highest court that Trump engaged in an insurrection against the United States and, accordingly, should be disqualified from the presidential election under Section 3 of the 14th Amendment.

Trump “refused to accept the will of the over 80 million Americans who voted against him,” the brief filed by Norma Anderson and several other plaintiffs said. “Instead of peacefully ceding power, Trump intentionally organized and incited a violent mob to attack the United States Capitol in a desperate effort to prevent the counting of electoral votes cast against him.”

Anderson, a Republican and former Colorado state lawmaker, and several other plaintiffs had filed suit in September 2023 to keep Trump off the 2024 Colorado ballots. The Colorado Supreme Court’s conclusion that Trump was ineligible to appear on the ballot was appealed by Trump to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The 14th Amendment’s Section 3 bars those who have “engaged in insurrection or rebellion” from holding federal office.

The outcome of the case will likely determine if Trump can appear on ballots in states across the country.

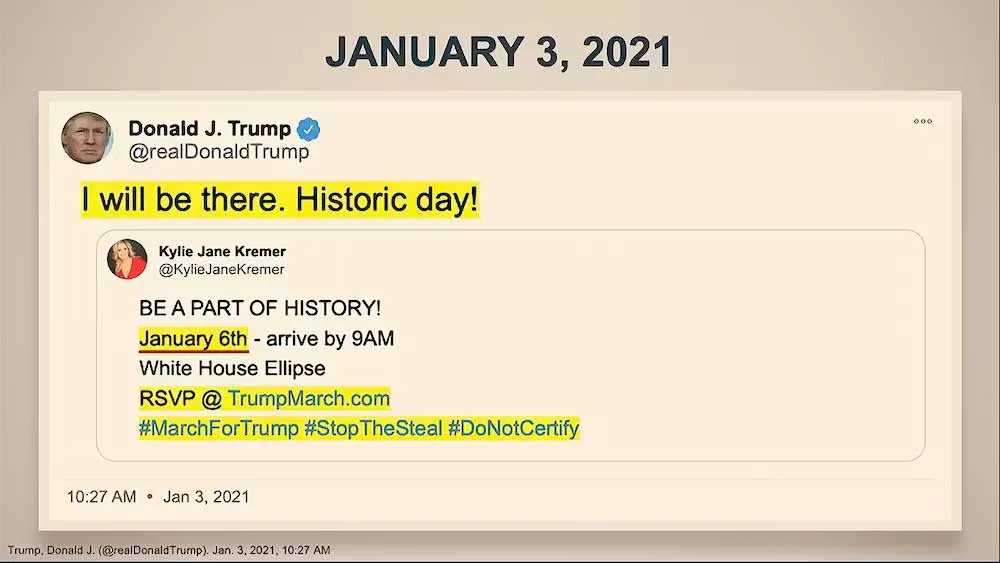

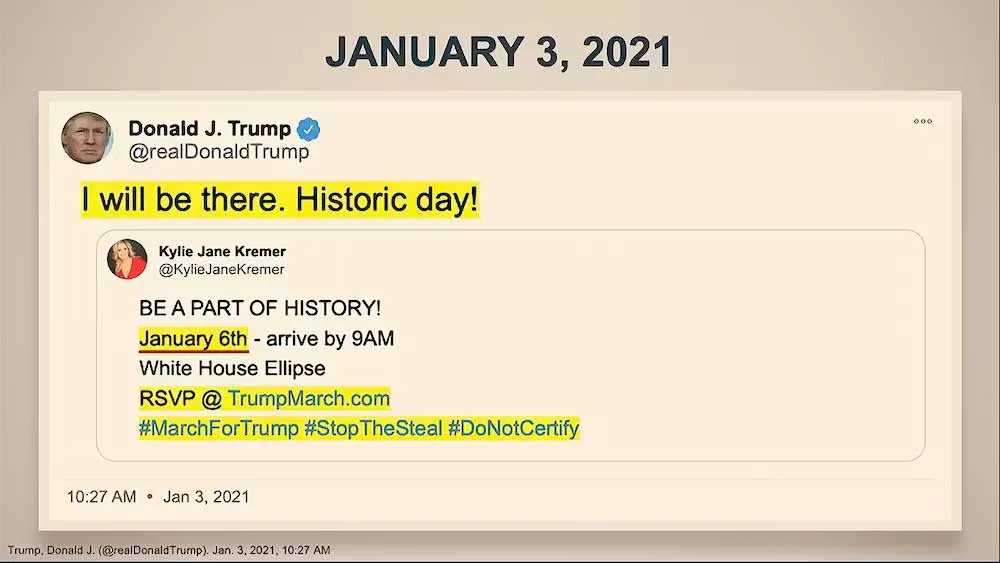

Tweet displayed for senators as House impeachment manager Rep. Eric Swalwell, D-Calif., speaks during the second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump in the Senate at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, Wednesday, Feb. 10, 2021. Image: Senate Television

Facts vs. Assertions

Unlike Trump’s brief, which he filed with the Supreme Court on Jan. 18, Anderson primarily focuses on the facts, pointing out that Trump’s brief lacks any meaningful rebuttal of the “most damning evidence against him.”

Some of the “most damning evidence” that Anderson’s brief highlights includes how Trump “deliberately summoned to D.C. an angry and armed crowd who came ready to fight” and that Trump’s speech on the White House Ellipse “explicitly and implicitly incited the angry and armed crowd to imminent lawless violence.”

The Anderson brief describes how the Jan. 6 attackers “injured over 140 law enforcement officers, left one dead, and forced Congress and Vice President (Mike) Pence to flee for their lives.”

In his brief, Trump mainly argued that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment does not apply to the presidency because the president is not an “officer” of the United States under the Constitution. Trump’s brief also argued that Section 3 does not bar a candidate from running for office but rather bars the candidate from holding office, if elected.

And Trump asserted in his brief that “Calling for peace, patriotism, respect for law and order, and directing the Secretary of Defense to do what needs to be done to protect the American people is in no way inciting or participating in an ‘insurrection.’”

‘Monumental’ Case

The Supreme Court will have several issues to consider in this case. The justices will have to address the legal questions presented by Trump, such as whether Section 3 of the 14th Amendment applies to the presidency. And the court will also have to answer mixed questions of law and fact.

Traditionally, the Supreme Court does not delve into questions of fact in the cases it considers—those facts are understood to have been established in lower court decisions. And while I initially stated that the court would not consider such questions in this case, I now join other constitutional scholars who believe the court will likely have to answer what constitutes an insurrection under the 14th Amendment, and whether Trump’s actions—or inactions—sufficiently meet that definition.

Perhaps the justices will turn to the history of the 14th Amendment to answer those questions. As Anderson’s brief points out, Congress and the states ratified the amendment, including Section 3, after the Civil War because they believed that oath-breaking insurrectionists could, if given the power of elected office, dismantle the country’s constitutional system from within. The 39th Congress considered Section 3 a necessary measure of self-defense—ensuring that those who had proven themselves faithless would be deprived of the political power to threaten the future peace and security of the United States.

But Section 3’s text may present the deciding factors for the court. Section 3 clearly states that “No person shall … hold any office, civil or military, under the United States.” It provides no language that appears to prohibit candidates from running for office.

Ultimately, Trump v. Anderson will be a monumental case. Regardless of its outcome, however, Anderson’s brief asserts that the “desecration of the U.S. Capitol by a mob of insurrectionists on January 6, 2021, will forever stain our Nation’s history.”

Wayne Unger, Assistant Professor of Law, Quinnipiac University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is a nonprofit, independent news organization dedicated to unlocking the knowledge of experts for the public good. We publish trustworthy and informative articles written by academic experts for the general public and edited by our team of journalists.

Help Support Factkeepers!

{"id":null,"mode":"form","open_style":"in_place","currency_code":"USD","currency_symbol":"$","currency_type":"decimal","blank_flag_url":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-content\/plugins\/tip-jar-wp\/\/assets\/images\/flags\/blank.gif","flag_sprite_url":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-content\/plugins\/tip-jar-wp\/\/assets\/images\/flags\/flags.png","default_amount":500,"top_media_type":"none","featured_image_url":false,"featured_embed":"","header_media":null,"file_download_attachment_data":null,"recurring_options_enabled":true,"recurring_options":{"never":{"selected":true,"after_output":"One time only"},"weekly":{"selected":false,"after_output":"Every week"},"monthly":{"selected":false,"after_output":"Every month"},"yearly":{"selected":false,"after_output":"Every year"}},"strings":{"current_user_email":"","current_user_name":"","link_text":"Leave a tip","complete_payment_button_error_text":"Check info and try again","payment_verb":"Pay","payment_request_label":"Factkeepers.com","form_has_an_error":"Please check and fix the errors above","general_server_error":"Something isn't working right at the moment. Please try again.","form_title":"Help Support Factkeepers","form_subtitle":null,"currency_search_text":"Country or Currency here","other_payment_option":"Other payment option","manage_payments_button_text":"Manage your payments","thank_you_message":"Thank you for being a supporter!","payment_confirmation_title":"Factkeepers.com","receipt_title":"Your Receipt","print_receipt":"Print Receipt","email_receipt":"Email Receipt","email_receipt_sending":"Sending receipt...","email_receipt_success":"Email receipt successfully sent","email_receipt_failed":"Email receipt failed to send. Please try again.","receipt_payee":"Paid to","receipt_statement_descriptor":"This will show up on your statement as","receipt_date":"Date","receipt_transaction_id":"Transaction ID","receipt_transaction_amount":"Amount","refund_payer":"Refund from","login":"Log in to manage your payments","manage_payments":"Manage Payments","transactions_title":"Your Transactions","transaction_title":"Transaction Receipt","transaction_period":"Plan Period","arrangements_title":"Your Plans","arrangement_title":"Manage Plan","arrangement_details":"Plan Details","arrangement_id_title":"Plan ID","arrangement_payment_method_title":"Payment Method","arrangement_amount_title":"Plan Amount","arrangement_renewal_title":"Next renewal date","arrangement_action_cancel":"Cancel Plan","arrangement_action_cant_cancel":"Cancelling is currently not available.","arrangement_action_cancel_double":"Are you sure you'd like to cancel?","arrangement_cancelling":"Cancelling Plan...","arrangement_cancelled":"Plan Cancelled","arrangement_failed_to_cancel":"Failed to cancel plan","back_to_plans":"\u2190 Back to Plans","update_payment_method_verb":"Update","sca_auth_description":"Your have a pending renewal payment which requires authorization.","sca_auth_verb":"Authorize renewal payment","sca_authing_verb":"Authorizing payment","sca_authed_verb":"Payment successfully authorized!","sca_auth_failed":"Unable to authorize! Please try again.","login_button_text":"Log in","login_form_has_an_error":"Please check and fix the errors above","uppercase_search":"Search","lowercase_search":"search","uppercase_page":"Page","lowercase_page":"page","uppercase_items":"Items","lowercase_items":"items","uppercase_per":"Per","lowercase_per":"per","uppercase_of":"Of","lowercase_of":"of","back":"Back to plans","zip_code_placeholder":"Zip\/Postal Code","download_file_button_text":"Download File","input_field_instructions":{"tip_amount":{"placeholder_text":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like.","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like."},"invalid_curency":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"How much would you like to donate? You can change this amount to anything you would like."}},"recurring":{"placeholder_text":"Recurring","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"How often would you like to donate this?"},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"How often would you like to donate this?"},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"How often would you like to donate this?"}},"name":{"placeholder_text":"Name on Credit Card","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter the name on your card."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Enter the name on your card."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Please enter the name on your card."}},"privacy_policy":{"terms_title":"Terms and conditions","terms_body":null,"terms_show_text":"View Terms","terms_hide_text":"Hide Terms","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"I agree to the terms."},"unchecked":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Please agree to the terms."},"checked":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"I agree to the terms."}},"email":{"placeholder_text":"Your email address","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your email address"},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Enter your email address"},"blank":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your email address"},"not_an_email_address":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Make sure you have entered a valid email address"}},"note_with_tip":{"placeholder_text":"Your note here...","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Attach a note to your tip (optional)"},"empty":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Attach a note to your tip (optional)"},"not_empty_initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Attach a note to your tip (optional)"},"saving":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Saving note..."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Note successfully saved!"},"error":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Unable to save note note at this time. Please try again."}},"email_for_login_code":{"placeholder_text":"Your email address","initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."},"blank":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your email to log in."}},"login_code":{"initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."},"success":{"instruction_type":"success","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."},"blank":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Check your email and enter the login code."}},"stripe_all_in_one":{"initial":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your credit card details here."},"empty":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Enter your credit card details here."},"success":{"instruction_type":"normal","instruction_message":"Enter your credit card details here."},"invalid_number":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card number is not a valid credit card number."},"invalid_expiry_month":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration month is invalid."},"invalid_expiry_year":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration year is invalid."},"invalid_cvc":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's security code is invalid."},"incorrect_number":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card number is incorrect."},"incomplete_number":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card number is incomplete."},"incomplete_cvc":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's security code is incomplete."},"incomplete_expiry":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration date is incomplete."},"incomplete_zip":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's zip code is incomplete."},"expired_card":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card has expired."},"incorrect_cvc":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's security code is incorrect."},"incorrect_zip":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's zip code failed validation."},"invalid_expiry_year_past":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card's expiration year is in the past"},"card_declined":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The card was declined."},"missing":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"There is no card on a customer that is being charged."},"processing_error":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"An error occurred while processing the card."},"invalid_request_error":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"Unable to process this payment, please try again or use alternative method."},"invalid_sofort_country":{"instruction_type":"error","instruction_message":"The billing country is not accepted by SOFORT. Please try another country."}}}},"fetched_oembed_html":false}

{"date_format":"F j, Y","time_format":"g:i a","wordpress_permalink_only":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/colorado-voters-tell-supreme-court-trumps-jan-6-insurrection-will-forever-stain-us-history\/","all_default_visual_states":"inherit","modal_visual_state":false,"user_is_logged_in":false,"stripe_api_key":"pk_live_40P3DgGDAHEP1QtJ0nOU4nms5JYHI8GbQ05dYiB1S8OPP5oMSIpOCCeeIawOyeW6bWDkDMWdUeggbhxOQTSA6aedu00ROAbhXBd","stripe_account_country_code":"US","setup_link":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-admin\/admin.php?page=tip-jar-wp&mpwpadmin1=welcome&mpwpadmin_lightbox=do_wizard_health_check","close_button_url":"https:\/\/factkeepers.com\/wp-content\/plugins\/tip-jar-wp\/\/assets\/images\/closebtn.png"}

![]()